This Day in Labor History: March 18, 1886

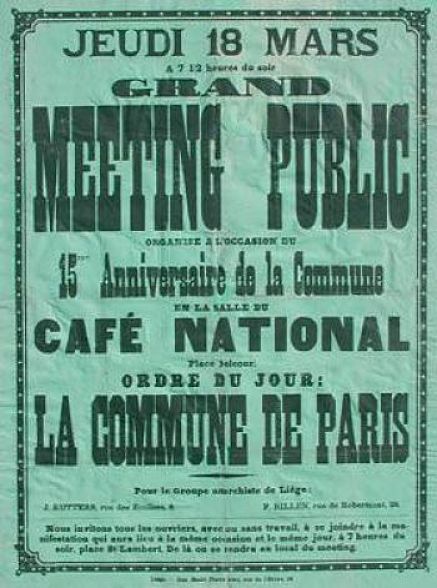

On March 18, 1886, anarchists in Liege, Belgium, held an action commemorating the 15th anniversary of the Paris Commune. Tapping into great dissatisfaction among the Belgian working class with their work, this small action grew into a much larger set of strikes that is one of the most important events in that great year of working class rebellion.

Now, it’s not that the Belgian anarchists had that much support. But when they called for an action on March 18, about 800 or 900 workers came out in support, many from the city’s largest metal works. This surprised the anarchists, led by August Wagener, as much as anyone else. In his speech that night, after marching through the day, Wagener told the workers:

“Citizens workers, you have just passed through the richest streets in the city. What did you see? Bread, meat, wealth and clothes. Well! Who provided this? Did you? You are all starving, you have no food, you have nothing on your bodies. No! No! Well, you are cowards.”

Telling Americans they are cowards in the face of rising fascism might not work but you know, Wagener had a point there.

It did not take the workers to respond to the challenge. They started breaking windows and throwing what would later be known as Molotov cocktails at the cops. Again, this surprised everyone. The anarchist group was new and had actually visited the mayor before the demonstration to say they expected maybe 40 people. But one thing about social change–you never know what is going to spark a particular movement at a particular moment in time. Why the Stonewall Riot? Why Rosa Parks refusing to get off her bus seat in Montgomery in 1955? It’s not as if gay people hadn’t resisted the cops before or Black women had never refused to move off a bus seat before. But sometimes, the time is right and it sparks something in the air that creates the conditions for a much broader set of actions. And don’t let other academic fields fool you–attempts to quantify protest behavior have no predictive value about the certain conditions under which a particular action will lead to something bigger than expected.

Worker leaders built on this moment and actions started spreading across the nation, especially in French speaking regions and centered in Wallonia. It’s not too surprising–conditions in Belgium were pretty bad. Beginning in 1882, Belgium had entered into a depression and that was still pretty strong by 1886. Really, this part of Europe had never really covered from what in the U.S. we call the Panic of 1873 but was really a global recession. Unemployment was high and those who had jobs were working 13 hour days. Spreading work around was a major labor demand through this period and for a long time after. Wages were rough and had gone down in the previous few years.

In fact, the next day, miners at the Charbonnage de la Concorde in Jemeppe-sur-Meuse. This probably did not have anything to do with the actions of the day before–they were just looking for a pay raise. But the timing tapped into this larger anger and helped fuel a bigger rebellion. A few days later, coal miners in the Chareloi basin went on the strike and they very much were responding to these larger issues. That the coal owners had chosen March 24 to lower their pay was a bad idea given the larger context. and on March 25 they walked out.

Workers were not messing around here. Some of the glass factories had started automating production, so the workers trashed them, figuring if they were not able to work, then the companies would not be able to exist. Seems reasonable. The Badoux glassworks were the biggest. The fact that Eugene Badoux himself lived in a giant castle nearby did not exactly calm the workers. Badoux had recently replaced coal with gas, allowing him to lay off lots of workers who had shoveled coal into the furnaces. Those workers wanted revenge, or more specifically, they wanted to recreate their power in the labor market that Badoux had destroyed. They raided the castle and trashed it, stealing all his fancy clothes and wall hangings and drinking his enormous champagne collection, which of course only fueled the joyous riot.

These property raids spread to a brewery and some blast furnaces. Most of Wallonia was in full rebellion. Moreover, this was not random violence. It was highly targeted against those industrialists doing the most to hurt the workers. It did not take long for the Belgian government to call out the military to crush the strike, with maximum violence if need be. It didn’t really take too long for the crushing to both begin and end. About twenty workers were killed in late March, including twelve in Roux on March 29.

But the aftermath of this strike demonstrates that in a sense, the workers won even as they were crushed militarily. The 1880s were a period when European politicians and business leaders began to admit they needed to come to some kind of arrangement with their workers. This was something American employers and politicians would resist for a very long time and in many ways continue to resist today. So this seemingly random uprising led to a surprising amount of concessions and reforms by the government over the next couple of years. Two glassmakers union leaders were charged with the riot that led to the destruction of that plant, but the nation’s leading socialist lawyer defended them and they were granted amnesty in 1888. Parliament created a Labor Commission that instituted some reforms.

Moreover, the Socialists themselves tried to rein in the anarchists and move working class discontent toward politics. Alfred Defuisseaux started his own party. He had been a member of the Liberal Party but was really a radical socialist. His A People’s Catechism, written during the strike, sold upwards of 500,000 copies around the small nation. While he would be convicted in abstentia after fleeing to France after the strike was crushed, his new Socialist Party became a major player in Belgian politics. Even on the right, the Catholic Party moved toward a more social Catholicism to address workers’ issues. Moreover, unions grew rapidly in the country in the following years. But of course, for all of this, no employer was turning their back on automation.

There was a further trial in 1889 that collapsed when it was discovered that the government had used agent provocateurs to stir up trouble. This only infuriated the public more against the conditions that had existed and fueled more energy into broader reforms.

I borrowed from Gita Deneckere’s “The Transformative Impact of Collective Action: Belgium, 1886,” published in International Review of Social History in 1993, to write this post.

This is the 555th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.