This Day in Labor History: September 14, 1889

Black guano workers on Navassa Island rose up and killed five white bosses in an act of desperation in revolt against a racist work regime. Working in some of the planet’s worst conditions, these American workers, largely tricked into going there without knowing of the conditions, lived in horrific conditions. Of course, despite evidence coming out about the reality of place, three of the workers were sentenced to death and never saw the light of day again.

You know what is not a good job? Digging guano. This became a big thing in the nineteenth century as the global economy required ever more intensive fertilization for crops. As the American empire expanded, it looked for guano resources and the best place was isolated islands in various oceans. These often tiny islands usually either had no meaningful imperial claim upon them or were under the control of weak nations, especially in South America. So workers with no other options, often bonded, had to dig out this guano. Imagining working in these isolated conditions, with bad food and housing, breathing in bird shit fumes. Now imagine getting a cut or scratch and having this literal shit enter your body.

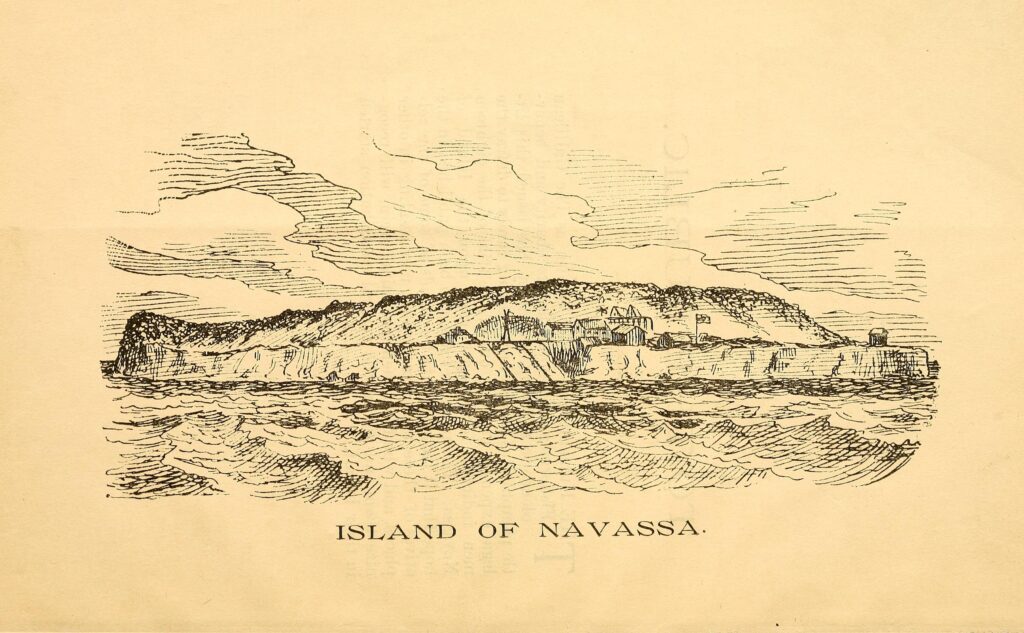

Navassa Island is off the west coast of Haiti, south of Cuba. Haiti claimed it but had no real power to do anything about it. Meanwhile, the U.S. also claimed it, by Captain Peter Duncan under the Guano Islands Act of 1856, which allowed any citizen of the United States to claim an unoccupied guano island in the name of the United States. Haiti was furious, but James Buchanan threatened military action against the nation. Both nations continue to claim the island to this day.

A company out of Baltimore eventually began developing the Navassa guano deposits. After the Civil War, guano mining began in earnest. The company brought 140 contract laborers from Maryland, all Black, with white supervisors. From almost the very beginning, workers were deeply horrified by what they encountered, which in addition to everything mentioned above, included the horrors of that kind of labor in tropical heat. And let’s be clear–these conditions were not spelled out for workers. The labor recruiters just lied to them. Promises of high pay and low hours belied the true reality. Instead, workers labored 12 hour days with armed white supervisors treating them as slaves, which was more or less true, at least for the length of the contract, which tended to be 15 months. To say the least, very few workers reupped for another tour. When workers suggested improvements to make their job easier, the response was the barrel of a gun. The provided “food” was filled with maggots. Then there was the company store. As one worker later stated, a shirt that cost him 30 cents in Baltimore was $2.50 at the store, and there were no other options.

Workers resisted this all the time. The first short strike happened in 1865. In 1870, the company had to increase security to stop workers from escaping the island by stealing boats. In 1871, the supervisors complained that workers were pretending they were sick to get out of work. Workers sued the overseer in 1881, but a judge dismissed the suit on the grounds of contradictory testimony. In 1882, violence erupted, which included the overseers shooting into the barracks, leaving one worker dead. Another worker smuggled a letter out describing what happened, which somehow got into the hands of President Chester Arthur, who ordered an investigation. But the captain of the ship doing the investigation said everything was great and you know what Blacks are like, amirite?

Finally, on September 14, 1889, the workers snapped. The final straw was the torture of one worker, a man named Charles Smallwood, who was hanged by his thumbs for two hours a few days earlier. When a sick worker was then threatened by being hanged by his feet, that was it. 137 rose up in violent protest. There were 11 whites on the island and they killed five of them. That happened after workers made demands and the response was violence from the guards. One worker was shot in the face, though only lost a tooth and then the workers, fearing for their own lives, made the split decision to take over the island. Some workers tried to flee of course. It’s hard to completely put together exactly what happened that day after first shooting.

Of course American newspapers described this in lurid terms about the darkies killing good white men. But Black newspapers started publishing true accounts of the violence and small numbers of white racial liberals started promoting them. This got the attention of bigger papers, including the Baltimore Sun and New York Times, who sent reporters down there. Now, the Times was no liberal paper and its record back in the day of reporting on race and labor was really bad. But in this case, the reporters were so revolted by the conditions at Navassa that they told a very different story than those first account. This became a legitimate civil rights case.

As a case about a Black labor uprising, the Navassa uprising was a good chance for everyone to relive the Civil War. In fact, the prosecution had a former Confederate named Thomas Hayes lead its case and he was on a path that would lead him to become mayor of Baltimore ten years later on a platform of naked white supremacy, with voters who wanted to be represented by a man who would stand up for the White Race. Three supposed ringleaders–Henry Jones, Edward Smith, and George Singleton Key–were tried for murder in Baltimore. Convicted, they received a sentence of hanging. Ten other men were sentenced to prison.

Conditions at Navassa did not improve after this. More workers protested, more even wrote to presidents about it. Benjamin Harrison commuted the sentences of the three workers to life in prison. Harrison himself called for Congress to pass a law regulating labor conditions on guano islands, but of course that didn’t happen. Workers continued to die there until the mine operations ended in 1898. All three of the men convicted of murder died in prison, despite continued attempts to get them freed, the last in 1911.

I borrowed from Dennis Patrick Halpin’s article, “‘All Manner of Cruelty and Slavery’: A Long History of Black Labor and White Violence on Navassa Island, 1857-1898,” published in the January 2024 issue of The Journal of African American History.

This is the 535th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.