My Reservations On Scary Nuke Stories

Vice Presidential candidate Tim Walz has read Command and Control by Eric Schlosserand found it terrifying. I was alerted to this by some of my followers on Bluesky. I responded that I have some reservations about the book, but it’s fine that he read it. If he and Kamala Harris win, he will learn of their even more terrifying responsibilities. He will get a “nuclear football,” a satchel with everything needed to start a nuclear war carried by a military officer who will be his constant companion. He may be learning even now, as he travels with Harris and the football.

My reservations are two: 1) I feel that the genre of recounting nuclear accidents to terrify people is counterproductive. Recounting these stories does not provide a way forward that can help people to change our situation. 2) Most or all of the horrifying accidents recounted in this genre happened some time ago and are no longer relevant, beyond the general idea that accidents can happen. The Damascus accident that is the center of Schlosser’s book happened in 1980. That particular accident cannot happen again in the United States.

Command and Control is generally accurate, which puts it among the best in this genre. The story of the Damascus accident, centerpiece of the book, checks with what I’ve heard from people who were there, including Bill Chambers, who found the nuclear weapon that had been blasted off the top of the missile. Terrifying indeed. I read the book several years ago and don’t recall any glaring technical errors.

For many years, the almost exclusive approach to persuading people to see nuclear weapons as something we need to deal with has been to recount accidents that have taken place, some frighteningly close to detonations, some involving lost weapons that might be retrieved by unfriendly actors, although it is hard to imagine those actors with the resources of the federal government, which failed to retrieve them. Another type of near miss written about is mistakes in interpreting radar and other signals for indications of nuclear attack.

But what these stories are likely to do is persuade people that these terrible weapons are out of their control, possibly out of anyone’s control. These stories provide no action for them except to call their Congressional delegation or join a group that lobbies for control or abolition of nuclear weapons. Both of those are unsatisfying, and perhaps irrelevant in a world where Vladimir Putin rattles his nukes to keep the US out of Ukraine and where a facist takeover more immediately threatens our government. Another danger is that their repetition flattens out their horror.

There’s another story that could be told of the time when Americans and Russians worked together to control nuclear materials in a broken Soviet Union and to disassemble as many as possible. As Martin Pfeiffer says in signing off from Bluesky, “We built them. We can take them apart.” That’s one of the things I worked on at Los Alamos – taking them apart.

The US now has 3,748 nuclear weapons, down from more than 31,000 at the Cold War peak in the 1960s. Still far more than any reasonable need, but we’ve disassembled a lot of them.

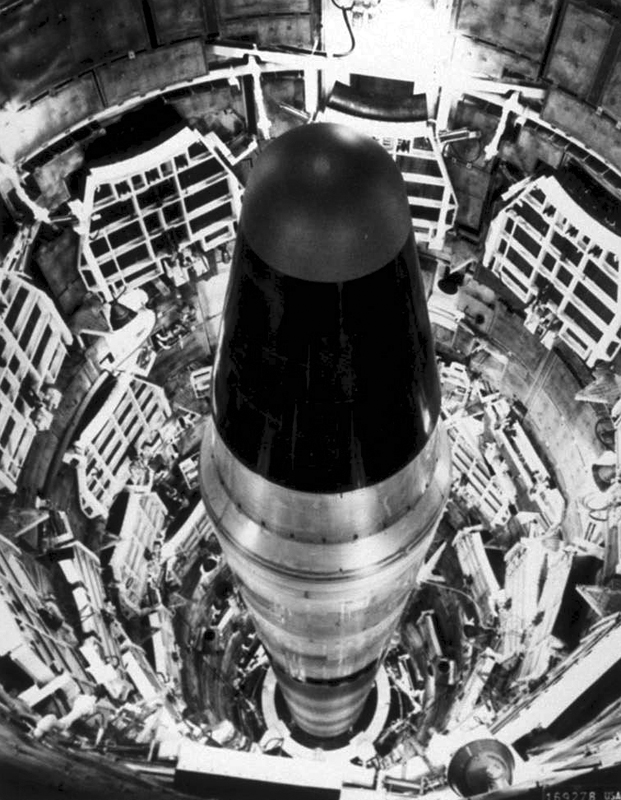

The Damascus accident happened in 1980, when the propellant in ICBMs was a mixture of two highly reactive and poisonous liquids. A service member dropped a wrench on the amazingly thin skin, which released one of the liquids. From that point, it was only a matter of time until the missile would blow up. The propellant in ICBMs now is a solid, less dangerous and finicky than those liquids. Even North Korea is moving toward solid-fueled missiles. Additionally, today’s nuclear warheads are designed to be safer in extreme situations.

The nuclear accidents often recounted happened with different and more dangerous nuclear weapons designs or in circumstances that no longer apply, like the 24-hour alert that kept nuclear weapons on flying airplanes constantly. Other accidents are possible, but the people who know about them are unlikely to talk. My own judgment is that accidents with nuclear weapons are less likely now than they ever have been.

If we don’t use these scare stories, how do we persuade people that we don’t need nuclear weapons? That’s particularly difficult right now.

Cross-posted to Nuclear Diner