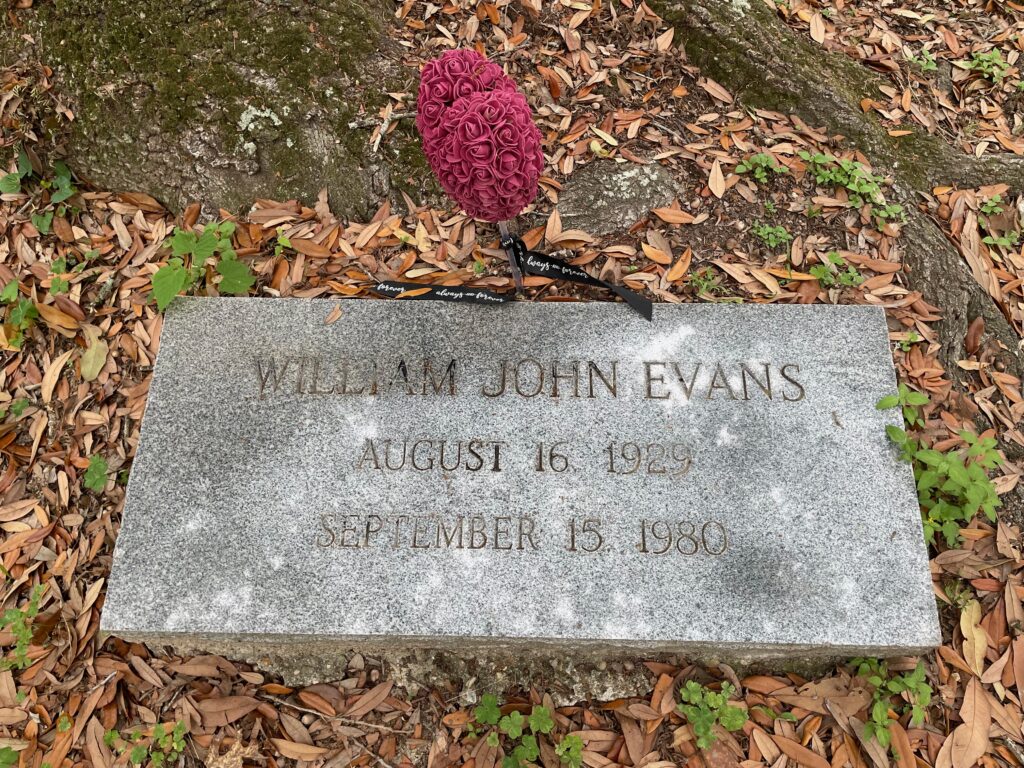

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,662

This is the grave of Bill Evans.

Born in 1929 in Plainfield, New Jersey, Evans grew up in a tough household, with an awful abusive drunkard father. But he found solace in music. He started taking piano lessons about the time he entered school. He would take lessons in flute and violin too. He was something of a prodigy and also had an unusual interest in exploring new music. So by the time he was 12, he was listening to Stravinsky and it was also about that time that he discovered jazz. Now, this didn’t totally come out of nowhere. His older brother Harry was the father figure in Bill’s life. As it happened, he also a trumpet player and by the time Evans was 13, was in Buddy Valentino’s band. He encouraged Bill’s music and was amazed at how good the kid was, so when there was an opening in Valentino’s rehearsal band because the pianist was sick, Bill got to take over for awhile. Quite an experience for a kid.

So by his early teens, Evans was in demand locally for dances and clubs in New Jersey. He met quite a few people–it wasn’t the center of jazz, but there were plenty of jazz bands around. He actually wasn’t fully committed to piano yet, amazingly. In fact, he would attend Southeastern Louisiana University on a flute scholarship. But shortly after that, he committed all the way on the piano. He graduated and started a band with a couple of his buddies, the guitarist Mundell Lowe and the bassist Red Mitchell. They would both have strong careers too. But they didn’t do much as a band. Evans got a job with Herbie Fields’ band in Chicago and they backed Billie Holiday on a three month tour in 1950.

Evans got drafted in 1951 and spent the next three years in the Army, mostly playing in Army bands. These were not good years for him. He hated the Army, people in Army bands didn’t like his style, he began to doubt himself, and he also began to dabble in drugs. This began to define his life. He was a complete 100% genius, one of the great pianists in jazz history, a man who would change the entire concept of the jazz trio, who also hated himself and self-medicated through heroin, which was all too common in jazz clubs and which some jazz fans still unfortunately romanticize to the present. He wasn’t quite on the heroin yet in the Army–that is where he began smoking marijuana. But the path started to become clear.

After trying to get his life together by living with his parents for a year, Evans went to New York in 1955 and began playing in local clubs. It did not take people long to get people’s attention. The problem was that Evans didn’t actually like attention, so you had to convince him to record. He had already written “Waltz for Debby,” one of the great classics. In September 1956, he went into the studio with the drummer Paul Motian and the bassist Teddy Kotick and recorded his debut album as a bandleader, New Jazz Conceptions. It did OK, but compared to his later work, well, it all needed to bake a bit longer. Nothing wrong with that. He started working with the composer George Russell, who took the kid under his wing. He started playing with everyone–Charles Mingus, Oliver Nelson, Art Farmer, all sorts of legends.

And then came Miles Davis. When Miles contacted Evans in 1958, it was supposed to be for a one-night deal, but he actually wanted a new pianist to replace Red Garland and so this was a bigger test. Evans of course aced it. He also was hugely influential on Miles. The ever-curious trumpeter had started moving into modal music and Evans knew way more about the contemporary classical world than Davis and so started introducing him to composers. He didn’t stay with Miles too long, though he did play on most of the tracks on Kind of Blue. But the influence was very real and both men were among the most forward-thinking jazz musicians of that rapidly changing era. Evans also wrote the liner notes.

Although it was right around the time Evans joined Miles’ band that he started using heroin (Philly Joe Jones gets a lot of blame for introducing Evans to the needle), he spent the late 50s and early 60s at the height of his powers, particularly when he created his iconic trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian. Portrait of Jazz and Explorations are key albums in the canon. Even more important is Sunday at the Village Vanguard, the live album the trio recorded in 1961, often considered a top-five all time jazz album. I don’t know if I’d go quite that far, but it’s obviously a super album.

Then Scott LaFaro died in a car accident in 1961. Evans was completely devastated and he was already on the edge of keeping himself together and so of course he found relief through more heroin. Evans was still recording and playing but all his money was going into his arm, to the point of having his heat shut off. He mostly kept going but the quality of the albums after the mid-60s are pretty uneven. There are some good ones but the music had changed a lot in that period, with Miles going electric and Coltrane and Coleman going into noise and neither mode really fit what Evans did. There are good albums for sure, working with people such as Stan Getz, Jim Hall, and the man who became his long-time bassist, Eddie Gomez. There were some periods of stability and some periods of drug use.

By the mid 70s, Evans was in a rut. He still hadn’t fully kicked the habit. He told his long-time partner that he had fallen in love with someone else. She killed herself. That didn’t help the heroin use, or the cocaine that he had turned to in that era like everyone else. He ended up working with Tony Bennett in the mid-70s, which is cool, but hardly the kind of music that was changing the world 15 years earlier.

Then Evans’ brother committed suicide in 1979. That was the final emotional blow for Evans. Speaking of blow, he started using several grams of cocaine per day after the death of his brother. It seems that he stopped caring about life. Having punished his body for decades, it finally gave out in 1980, with about 15 things wrong with it. He was 51 years old. Evans’ friend, the critic and lyricist Gene Lees, called it “the longest suicide in history.” Mostly, it’s just sad to see a complete genius destroy his life. But he’s not the first and especially in that world where drugs were so available and common.

Let’s listen to some Bill Evans.

Bill Evans is buried in Roselawn Memorial Park, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

If you would like this series to visit other jazz legends who played with Evans, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Scott LaFaro is in Geneva, New York and Oliver Nelson is in Inglewood, California. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.