This Day in Labor History: April 28, 1911

On April 28, 1911, the South African government passed the Mines and Works Act that banned Africans to unskilled work in the mines and on the railroads. This especially what became the known as the Colour Bar in South African work, a key moment on the road to official apartheid. Work was always central to the development of apartheid and a worthy topic to explore here.

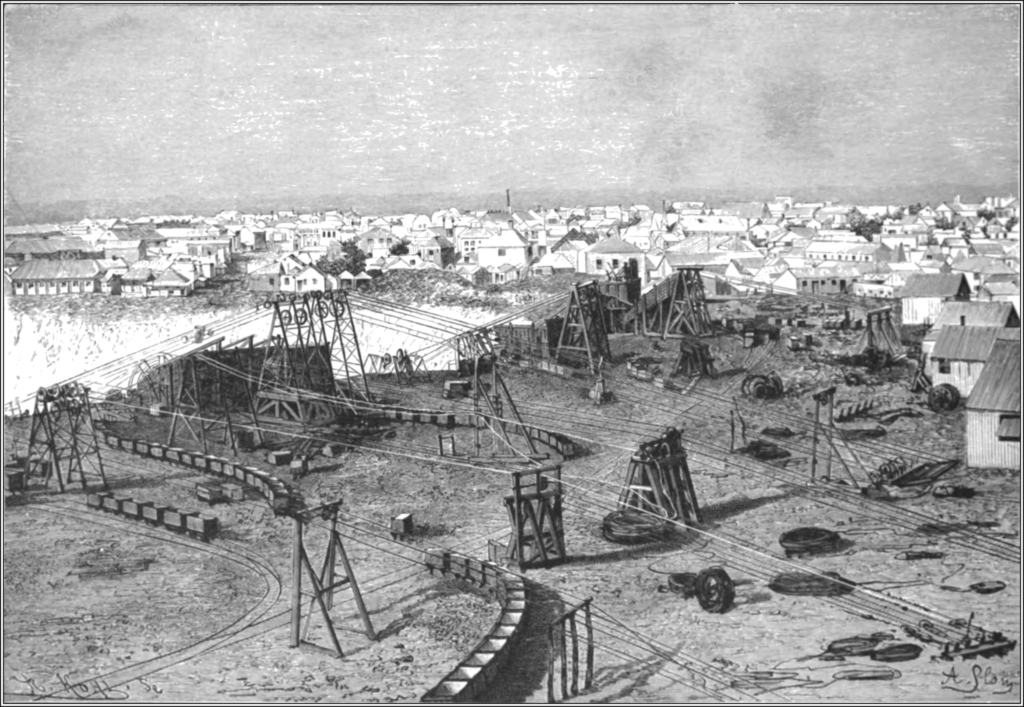

South Africa was founded on the basis of racial discrimination. When mining became central to the South African economy in the late 19th century, immediately forms of racial discrimination were institutionalized. The early diamond mines had Afrikaners as skilled laborers and Africans as unskilled laborers. Now, there was something reasonably natural about this initially, in that some whites had brought mining skills with them from Europe, but that got put into law pretty quickly. The first legal color bar was in 1893 in the Transvaal, where a law was promulgated that required skilled white blasters to be who set off the necessary underground explosions. The stated justification was safety, but of course that was at best a tiny bit of it. An 1898 followed up by saying that no colored person could hold an engineer’s certificate of competency.

By the early 1910s, South African leaders and white workers wanted to combine a better regulatory regime of workplace safety with a regulatory regime of whiteness. As originally written, the Mines and Works Act simply regulated that “white workers [received] a monopoly of skilled operations.” It did not mention Black or Asian workers at all. But it did allow the Governor-General to revoke mine owners and workers ability to operate if they did not cater to white workers. This wasn’t real hard to enforce as no one who owned these mines really cared about non-white workers. But they might have to pay these white workers a bit more. There was also the question of the “Coloured” workers, by which they mixed race people, as well as “Asian,” which mostly meant Indians. The law combined this racialization of the workforce with a national mine inspection mandate that allowed the Minister of Mines to inspect them for over safety. Before this, the color bar was only in the Transvaal, but this expanded that three other provinces. Future additions would expand it nationally.

This was all part of a much broader swath of legislation at this time that sought to enforce apartheid-level segregation. The Natives Land Act of 1913 followed that created the reserves for the African population that was only 1/10th of South African land and banned them from owning land outside of the reserves. The Native Act of 1923 created segregated urban areas. There was a lot of legislation like this.

The initial law protected 32 different job categories for whites. The Mines and Workers Act was amended and strengthened both in 1912 and then again in 1926. The 1912 Act made it more specific which jobs were designed strictly for whites. In 1918, another 19 occupations were reserved for them. The 1926 act did open the door a bit for the Coloured population. The idea here was that a lot of these people had learned the Afrikaner language and basically felt about Africans the same as the whites did.

South Africa protected white workers in other fields in different ways. For example, the 1922 Apprenticeship Act set in law that in order to be apprenticed in that nation, you needed to have reached at least Standard VI, which was the top grade in primary schools. But of course Africans hardly ever reached that level of education and by 1938, that number was only 2 percent. So even if South African law didn’t explicitly protect many workers by race, it found lots of other justifications to do so that would effectively create a fully segregated workforce.

The upshot of all this was to create solidarity between the white working class and employers on the lines of race. There was plenty of tension between leftist workers and employers in South Africa, as events such as the Rand Revolt of 1921-22 would show, but it was always blunted by their racial solidarity.

So the really critical take away from the Mines and Works Act is that it was one of the first major pieces of legislation creating the modern apartheid state and that this started at the mining workplace. I hesitate to call it the first, only because I don’t know South African history as well as others. But I will note that Jock McCulloch’s 2012 book South Africa’s Gold Mines and the Politics of Silicosis, starts the list of the key apartheid legislation with the Mines and Works Act. So it is at least a reasonable argument to make here.

I borrowed from C.H. Feinstein, An Economic History of South Africa to help me write this post.

This is the 516th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.