This Day in Labor History: April 17, 1941

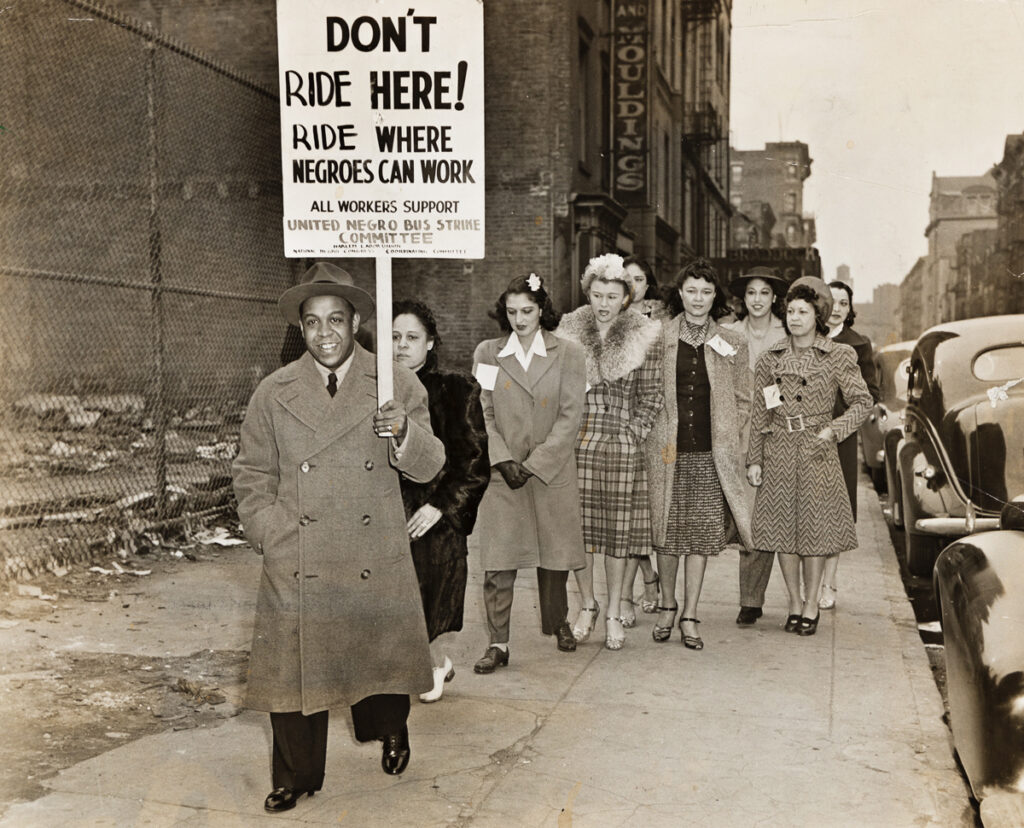

On April 17, 1941, two New York bus companies and the National Negro Congress came to an agreement to end the NNC’s boycott of city’s bus companies that had started a few weeks earlier over the refusal of the city to hire Black drivers. This was an important moment in both civil rights and labor history. It also launched the national career of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. is a complex figure in American history and the history of civil rights activism, but he certainly knew his power when he wanted to use it. Pastor of Abyssinian Baptist Church, he was well-aware of the discrimination his members faced. Meanwhile, the United States was about to engage in a war against two extremely racist world powers, but was completely unwilling to face its own racism. Black leaders were disgusted and determined to change this. Most famously, A. Philip Randolph led the March on Washington Movement in 1941 that forced a reluctant and indifferent Franklin Delano Roosevelt to issue an executive order forcing open the hiring of Black workers in firms receiving federal defense contracts, which as the war picked up, was basically most of the economy. That did not change everything–there was a lot of mass resistance in companies and federal regulators were slow to act–but it did make a huge difference over time and helped lay the groundwork for the postwar civil rights movement.

But Randolph was not this sole leader. There was a lot of Black economic rights organizing in these years, including campaigns to not shop where you could not work. There were also important city-wide campaigns and probably none more so than what was about to happen in New York. The city contracted out with private bus companies. Two of them refused to hire Black drivers or workers of any kind except for the most menial of jobs. The two companies had a total of 3,202 workers. 14 were Black. They were all porters.

The Black community in New York had been outraged by these exclusions since at least the mid-30s, when a city report castigated the companies for their whites-only policies. By 1940, 40 percent of New York’s Black population was either on some sort of assistance, unemployed, or severely underemployed. That was rates far above white populations as the Depression ended.

On March 10, 1941, the Transport Workers Union, led by Mike Quill, went on strike against the companies for unrelated reasons. Now, Quill was quite a union leader but he wasn’t going to push his members too hard on integration. So he was happy to have the support of the Black community, which came out against the companies, but the rank and file TWU member was pretty much fine with the all-white policy. The strike lasted for twelve days and was a big win for TWU.

This win had motivated the Black community to keep the pressure on the companies. While Powell is certainly the most famous of the figures organizing around these issues, he was far from the only one. The Harlem Labor Union was a Black worker organization under the leadership of Roger Straugh. It made alliances with Powell’s Greater New York Coordinating Committee for Employment and the Hope Stevens led Manhattan branch of the National Negro Congress.

On March 24, with Powell as the key spokesperson, the coalition announced a boycott. Quill and Powell had worked out a deal beforehand. He said that if the coalition won, the TWU would consider the membership applications from every Black worker hired, so long as said person did not have a history of scabbing. Over 1,500 people gathered at Powell’s church and announced the boycott.

Black-led bus boycotts always had a good shot of winning because it was a cheap transportation. While in New York, cars were always less common than other cities, still, whites who could tended to drive or take the subway. Since the white parts of Manhattan especially were better served that Black neighborhoods by the subway, African Americans tended to be on buses at numbers larger than the overall demographic presence. In other words, they could really hurt the bottom line.

This was a well-organized action. Soup kitchens and such developed to feed people who might not be able to get to their jobs, or who needed food anyway. People who did have cars volunteered them to get people around who really needed to get somewhere they couldn’t walk. But really, the ability to use the subway made the victory much easier. You just had to get someone to a subway station and make sure that you had enough donations that they could pay for a ticket.

Powell really pushed nonviolent ideas here, which were not quite articulated in the way that King would 15 years later, but were about both strategic moves and the moral superiority of Black people to racist bus companies. The TWU played a key role here. Already during the strike, Quill had worked hard with the local Black community to stop the use of their members as strikebreakers, a common use for scabs that would divide workers by race. Quill also wanted to build support in the community for support in upcoming negotiations between the city and TWU-represented subway workers. It was very much in Quill’s interests to build these relationships and even if some rank and file members didn’t like, have a fully integrated unions.

Pressure grew on the companies. Finally, on April 17, they came to a deal. The companies agreed to immediately hire 100 drivers and 70 mechanics and other maintenance workers. It wasn’t a ton, but it was a real win. They came to a quota agreement as well–17 percent of the workforce would be Black and the companies would hire 50 percent Black workers until that 17 percent was reached. Literally, they would switch off hires by race. Mike Quill agreed to this too and helped the union accept Black members.

This boycott also served as the launching point to Powell’s political career. Later in 1941, he was elected to the New York City Council and then entered Congress in 1945, where he would be an enormously influential figure and one of the most important political figures in Black history.

I borrowed from William P. Jones, The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights and Dominic Capeci’s 1979 article “From Harlem to Montgomery: The Bus Boycotts and the Leadership of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. and Martin Luther King, Jr.” to help with this post.

This is the 513th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.