Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,594

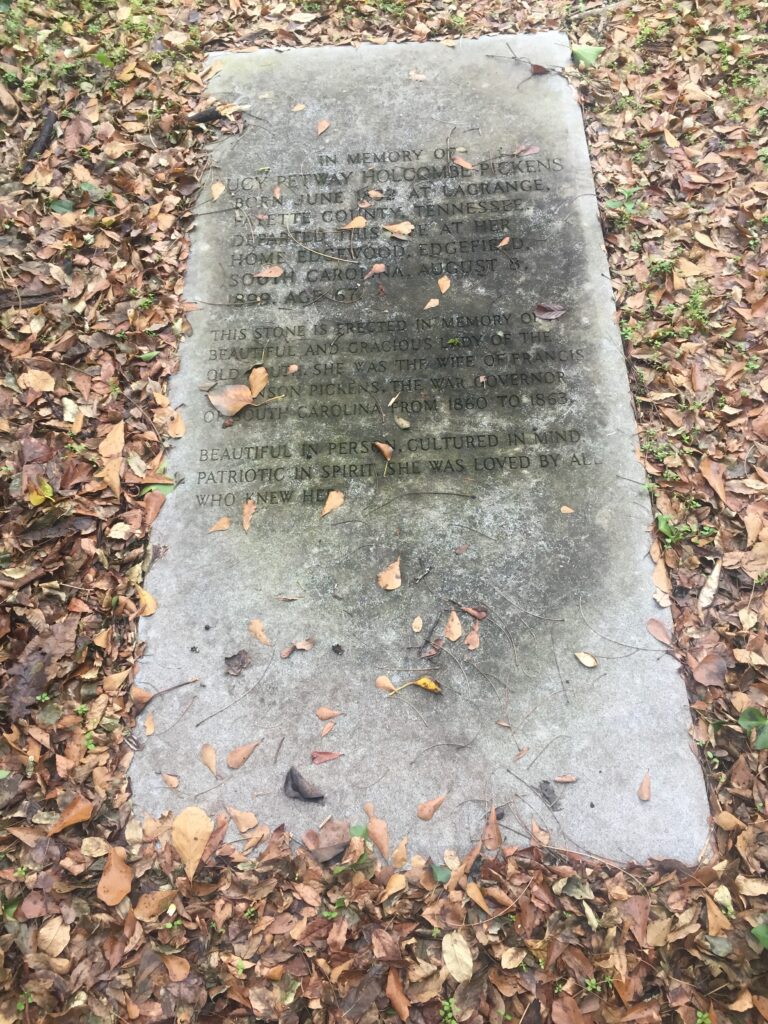

This is the grave of Lucy Pickens.

Born in 1832 on her family’s plantation near LaGrange, Tennessee, Lucy Holcomb grew up at the peak of the southern elite. She went to fancy schools in the South and even went to a finishing school in Pennsylvania. The family moved out to a big new plantation in Texas and Lucy joined them after finishing her school. She began to write romantic tales of the heroes of slavery expansion, including a story about the 1851 failed attempt by Narciso López and a bunch of southern extremists to take Cuba from Spain and attach it to the U.S. as a slave state. The Free Flag of Cuba, or the Martyrdom of Lopez: A Tale of the Liberating Expedition of 1851 was published in 1855.

Now, a young elite like Holcomb wasn’t right for any man. Nope, only a true southern elite would be for her. In 1857, she met Francis Pickens. He was 30 years old than she and John C. Calhoun’s cousin. He had outlived two wives and was looking for a fresh young lover of slavery. He sure found that in Lucy. She resisted at first. But then James Buchanan named Pickens Minister to Russia and upon hearing that, she accepted his proposal. Now Lucy Pickens, she immediately accompanied him and some household slaves to St. Petersburg. There, they were close to Czar Alexander II. She was really living the elite life now. In fact, Alexander and his queen were the godparents to the daughter she bore while in Russia. They were legitimately that close. Pretty good for a little slaver girl.

But of course things were changing at home. Can you believe it, some Americans were not happy with holding humans as chattel property! To say the least, Pickens and her husband were the kind of southern extremist who were happy to commit treason in defense of slavery. They returned home in 1860 to Francis’ plantation in Edgefield, South Carolina. When the traitors left, they elected Frances Pickens governor and so Lucy became the state’s first lady.

It wasn’t just that though. This makes them sound like regular Confederate elites. But this went further. Pickens became one of the heroes of the Confederacy, as the ideal of southern womanhood making the sacrifice of their men and even perhaps their (gasp!!!) slaves for a short time for the right to hold human property in perpetuity. The Confederacy was openly propagandizing about the issue. She very much believed in the hierarchical traditional gender roles that the South promoted, where the plantation owner was the father figure to all, including his wife, and his dictates should be followed by a faithfully sacrificing wife/servant. Slaves were happy in this vision and slavery an outright good. In essence, Pickens, even before the war, provided the intellectual vision that would become the hazy romantic antebellum myths after the war.

In November 1861, a force of South Carolina soldiers named their unit the Holcombe Legion in her honor. This was basically sucking up to Francis Pickens. He had asked his buddy Peter Stevens to raise a regiment and so Stevens named it for her. They were mostly destroyed at Second Manassas, though it existed in some form or another for the whole war and its successor was at Appomattox. People have claimed that she funded the regiment by selling the jewels given to her by the Czar, but I don’t think there’s any actual evidence here. Confederate propagandists and the century of Confederate nostalgia pushers loved stories like this.

As the ideal of southern womanhood, the Confederate government chose to use Pickens as a way to promote itself. She was the face on several versions of Confederate money (nothing more worthless that Confederate paper, even during the war), including for awhile, their $1 bill. The idea behind this came from a printer in South Carolina and the Confederate government was cool with it. They weren’t exactly thinking that hard about their paper money, even though they should have been. But in that place and time, Pickens’ extremely traditional visions of gender were perfect for propaganda purposes. She most certainly did not object to having her face on the money.

In fact, during the war, Lucy Pickens was mostly at her husband’s plantation, where she had to deal with running it on her own (a common issue for planters’ wives who were never allowed to make any decision at all when the man was around but now had to do it all) all while dealing with Pickens’ daughters from his previous marriages who were about her age and did not like the interloper. But she was a lot more than this. She was the confidant to many southern leaders. She fancied herself a political figure and intellectual as much as a slaver and plantation wife. She was a deeply political being for sure, to the point that other leading Confederate women such as Mary Chesnut looked up her as a huge gossip and with some contempt. When she was in Charleston or Columbia, Pickens did her gendered duty, visiting wounded soldiers and sometimes doing fundraisers for the soldiers and for hospitals, where she made the slaves dress in Russian costumes, pulled out the samovar, and did some exotic stuff for the guests.

After the war, Francis took the loyalty oath Andrew Johnson demanded and Lucy sold some more of her Russian jewelry to raise money to help the legal defense of leading Confederates. The loss of all the slaves sent the Pickens on an economically downward slide. Hoping to save the South Carolina plantation, they sold off their properties in Mississippi and Alabama. Francis died in 1869. Lucy was still only 37 and she had to take over the management of the declining fortune. She at least stemmed the losses to some extent, in part by actually paying people to work and thus some would.

Pickens spent her later years involved in the growing Confederate nostalgia movement, She was a central figure in raising money for Confederate statues and her status as the white womanhood ideal in the South during the war gave her a lot of regional cultural capital in these last decades.

Pickens died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1899. She was 67 years old.

Lucky Pickens is buried in Edgefield Village Cemetery, Edgefield, South Carolina.

If you would like this series to visit other leading Confederate women, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Mary Chesnut is in Camden, South Carolina and Belle Boyd is in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin, even though she was a key Confederate spy in the Shenandoah Valley during the war. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.