There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes

This story on how my semi-home town (went to high school there; a lot of family still there) is handling the morphing of the drug overdose epidemic from an opioid to a broader-based problem is, non-facetiously, sobering.

Medications like methadone can safely replace more destructive opioids and satiate the brain’s opioid receptors. But subduing the urge for stimulants, which set off the release of stratospheric levels of the brain chemicals dopamine and serotonin, is more complex, involving many unknowns. And Narcan, which has saved at least hundreds of thousands who overdosed on opioids, has no effect on stimulants.

Moreover, depending on whether the user routinely turns to cocaine, meth or prescription amphetamine, side effects, responses and behavior patterns vary greatly.

“The truth is, we really don’t have a good answer at this point as to why it’s so challenging to develop these treatments,” said Marta Sokolowska, the deputy director for substance use and behavioral health at the F.D.A.’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

Last year, according to preliminary federal data, stimulants were present in 42 percent of overdose deaths that involved opioids.

Like opioids, which originally came from the poppy, meth started out as a plant-based product, derived from the herb ephedra. Now, both drugs can be produced in bulk synthetically and cheaply. They each pack a potentially lethal, addictive wallop far stronger than their precursors.

In recent decades, opioids grew so dominant that meth and its stimulant cousins proliferated in the shadows.

A decade or so ago, Mexican drug lords figured out how to mass-produce a synthetic “super meth.” It has provoked what some researchers are calling a second meth epidemic.

Popular up and down the West Coast, super meth from Mexican and American labs has been marching East and South and into parts of the Midwest, including Grand Rapids and Kalamazoo.

Users inject, snort or ingest meth, often seeking to prolong its euphoria with binges that can last for days. Meth can also trigger violence and psychosis that emergency doctors can mistake for schizophrenia. Its long-term effects include anhedonia and memory loss.

Rates of drug overdose deaths in the US more than quadrupled between 1999 and 2020, rising from 6.9/100K to 30/100K. And they’ve almost certainly risen further since then.

This is just the most obvious and extreme example of the ravages of what the historian David Courtwright calls “limbic capitalism.” The only difference between Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman and the Sackler family is that El Chapo isn’t going to get a building at Harvard named after him (probably; the century is still young). But it’s not just the Sacklers, or for that matter the legal drug industry — not by a long shot:

Economists make a distinction between durable and non-durable goods. Limbic capitalism is mostly about problematic, non-durable goods. You smoke a cigarette, and it’s gone. You go to Las Vegas and drop $10,000. Limbic capitalist enterprises, whether they are licit or illicit, whether they’re supported by the government or not, are predicated on providing goods and services that produce quick hits of brain reward. And those brain-rewarding products operate on and through your limbic system, a very ancient part of your brain that deals with pleasure, motivation, and long term memory.

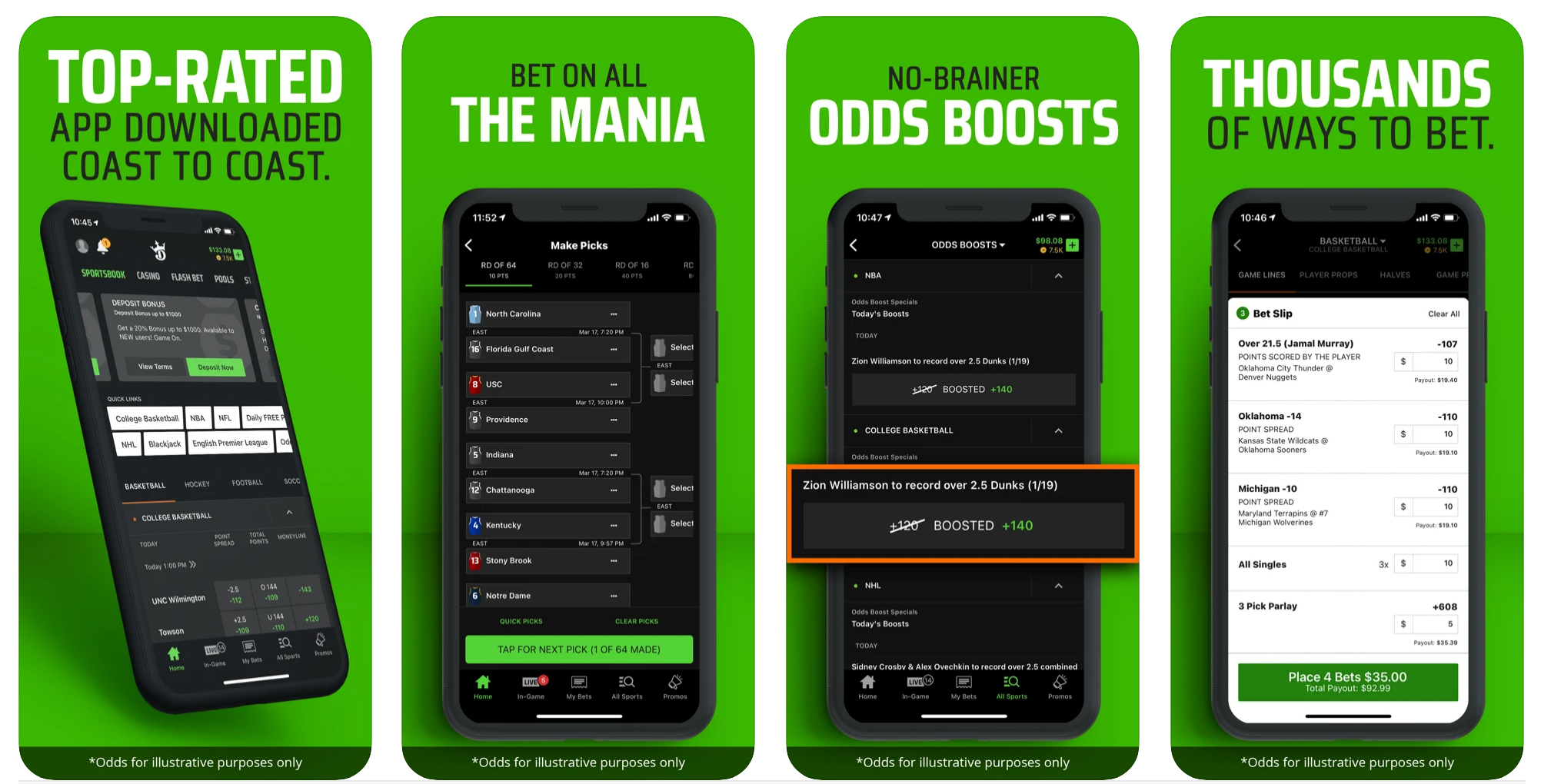

Limbic capitalism is enormously profitable, but it’s socially regressive. If you look at virtually any limbic capitalist enterprise, the vast majority of their revenues come from 10-20% of their customers, the heaviest customers, and especially the addicted customers. The other disturbing piece here is that they target the young. They want lifetime heavy consumers. If a person has reached the age of 25, the chance they’re going to start smoking cigarettes is very, very low. Bad habits typically form early in life, and limbic capitalist entrepreneurs know that. . . .

I frankly acknowledge that there’s much joy to be had in these pastimes and products. A glass of good wine with a meal, occasionally experimenting with drugs, playing a few games on the Internet—that can all be fun, a nice break, liberating in many ways.

But the problem with limbic capitalism is that you can’t make any serious money if people only occasionally do these things. We’re in an economy that’s increasingly predicated on attention and surveillance. The logic of the system is to push consumers toward heavy consumption and, at the extreme of that spectrum, you get compulsive, harmful consumption. And that’s what the problem is: to make sustained profits, to keep your shareholders happy, you have to push in that direction.

As someone put it, the tag lines at the end of liquor and gambling commercials — “Please drink/wager responsibly” etc., can be translated accurately as “Please put us out of business.”

The ideal thing would be to build a society where a lot fewer people were prone to destroy themselves and their families with one or more of the endless assortment of addictions that limbic capitalism offers up, but that would lead to a lot fewer super yachts and private jets, so . . .