This Day in Labor History: November 13, 1986

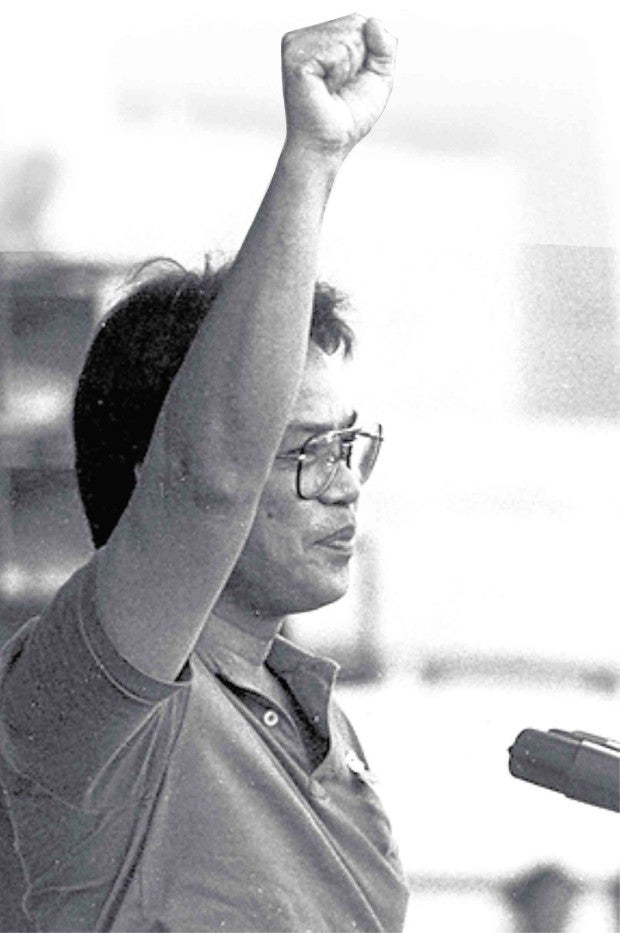

On November 13, 1986, the Filipino labor leader Rolando Olalia was assassinated by military officers infuriated by the loss of dictator Ferdinand Marcos and their belief that the labor movement was dominated by communists. This moment of murderous response to the rise of labor organizing was not atypical of the Global South in these years, but in truth, neither Marcos nor his better replacement Corazon Aquino had much sympathy for the workers’ struggle.

By the 1970s, with the rise of the modern version of globalization that centered around aggressive capital mobility, a lot of low-ended industry started arriving in the Philippines. This was especially true of textiles, moved forward rapidly by the complete indifference of the Carter administration to keeping any of these jobs in the United States. For a dictator like Marcos, this was great. He could rake in the money and guarantee textile companies that no pesky unions would bother them there. They could have all sorts of tax breaks with the power of the government ensuring that labor costs remained low. These sweatshops became the places where young women, many of who were recent migrants from the countryside to cities such as Manila, went to work.

The Philippines had a fairly active union movement and from nearly the moment that the factories opened, union organizers attempted to bring the workers together to fight for their rights. But this is where the Marcos regime came in. Marcos would order these organizers beaten, jailed, tortured, even killed. Marcos was pretty good at this. He was a mass murderer. For him, anyone who threatened his control over the nation was a communist, whether other elites such as the Aquino family or labor organizers. He ordered about 3,000 executions over the 21 years of his awful regime. In 1974, the Filipino Congress had offered a very limited place for unions in the government as a way to undermine the influence of communists. But they were only tolerated if they did not challenge Marcos and informed for the government on radicals. So these were not effective unions at all.

By 1980, grassroots anger at these bought and sold unions and the Marcos administration was rising. This was personified in the May First Movement, or KMU in Tagalog. This was a communist led movement that would soon have 400,000 members and, among other things, criticized the AFL-CIO for being hacks of Marcos, which was certainly true given how the federation under George Meany and Layne Kirkland were more concerned with killing communists abroad than in organizing workers anywhere. By 1982, 26,000 garment workers in the Bataan Export Processing Zone launched a huge strike and despite the military going in there and raising hell, they actually won the strike. The main demands were for higher wages and an end to sexual harassment, always endemic in the textile industry.

In the aftermath, Marcos went hard after the KMU, with American support of course. Olalia was an attorney by training who did a ton of work for the Filipino working class. But in February 1986, Marcos was finally forced from power and the reformer Corazon Aquino took over the presidency. The military was furious. A fascist movement developed in the upper ranks called Rebolusyonaryong Alyansang Makabansa (RAM) to plot a coup, eliminate the leftists, and reinstate Marcos or someone like him. In short, this was not too different than how the military acted in Chile to get rid of Salvador Allende and install Augusto Pinochet in power in 1973.

On November 13, 1986, the military went after Olalia. Along with his driver Leonor Alay-ay, Olalia was shot and killed. First, Olalia was stabbed a bunch of times. There were 12 men directly involved. They didn’t hide it. People knew who they were. But Marcos sure didn’t care. It became quickly known that RAM was not only involved in this, but that they saw it as a precursor to launch a coup against Aquino. She acted immediately and took action against the RAM leaders. Their coup didn’t work. But good luck getting justice here.

In terms of labor though, while Aquino most certainly was not the monster Marcos was, she was hardly some great leader for the working class. But some of this was the times. The finances of the Philippines were a mess thanks to all the debt Marcos had run up to keep his power. So then the International Monetary Fund and World Bank and the United States came calling for those debts. Neoliberal restructuring followed that Aquino agreed to implement, destroying what existed for a social safety net and expanding free trade zones that encouraged more western companies to use the nation’s cheap labor to move jobs from nations such as the U.S., or by this time South Korea and Taiwan, to the Philippines. The KMU kept organizing after Odalia’s murder and launched another strike in 1990, but wages have basically stagnated in that country’s industrial zones since then. Five years after their peaceful revolution that got rid of Marcos, the lives of workers were just as terrible as they were before. And this time, it was clear that the Global North financial institutions and the governments behind them were obviously responsible for this.

Finally, in 2021, the Filipino legal system went after some of the people directly responsible for the assassinations. Fernando Casanova, Dennis Jabatan, and Desiderio Perez, all military officers, were found guilty of two counts of murder and received prison terms of up to 40 years, in addition to paying about $2.1 million in restitution to the families. There were of course other people involved and some of them still remained very powerful. One of them, an officer named Red Kapunan, was the nation’s ambassador to Germany in 2021. So he was untouchable. The others were named Cirilo Almario, Jose Bacera, Ricardo Dicon, Gilbert Galicia, Oscar Legaspi, Filomeno Maligaya, Gene Paris, Freddie Sumagaysay, and Edger Sumido. They were all either in hiding or out of the country by 2021.

There is still a union movement today in the garment factories of the Philippines, but it also faces the continued global race to the bottom, with companies constantly threatening to move to Bangladesh if the wages go too high. It’s no wonder then that so many of the Filipino working class have turned back to strongmen such as Rodrigo Duterte to channel their frustrations. Thanks to American support of neoliberal institutions, democracy has been no better for them than dictatorship.

I drew from Annelise Orleck, We Are All Fast Food Workers Now: The Global Uprising against Poverty Wages to write this post.

This is the 504th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.