The Federalist Society Constitution has no room for an Establishment Clause

The nature of the current Supreme Court supermajority is such that the ACLU isn’t even bringing a federal claim in a case that as recently as a decade ago would have been considered an easy case of an Establishment Clause violation:

Last June, a previously obscure Oklahoma state board voted to allow two Roman Catholic dioceses to operate a charter school in that state. Lawyers from several civil rights organizations, including the ACLU, responded just over a month later with a lawsuit alleging that this state-funded religious school violates the state constitution.

This challenge to the religious charter school, known as St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, should be a slam-dunk — at least assuming that the allegations in the lawsuit are correct.

Charter schools are public entities funded by state tax revenue. Among other things, the complaint points to a provision of the Oklahoma Constitution which provides that public education funds may not be “used for any other purpose than the support and maintenance of common schools for the equal benefit of all the people of the State.” And several school policies described in the complaint indicate that St. Isidore does not intend to operate for the equal benefit of all students.

According to the lawsuit, the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City, one of the two dioceses that plans to operate this school, has a policy of expelling students who “intentionally or knowingly” express “disagreement with Catholic faith and morals.” This includes a rule that “‘advocating for, or expressing same-sex attractions … is not permitted’ for students,” and also a rule providing that a student who “reject[s] his or her own body” by beginning a gender transition “will be ‘choosing not to remain enrolled.’”

Yet the most striking thing about this legal complaint is what it does not say. The lawsuit states explicitly that “the plaintiffs’ claims for relief are brought solely under the state constitution, state statutes, and state regulations.” It does not even mention the federal Constitution’s First Amendment, with its prohibition on laws “respecting an establishment of religion.” Before a series of recent Supreme Court decisions carved up this establishment clause, a lawyer challenging government funding of religion almost certainly would have raised some claim under this clause.

And there’s very good reason to worry about the kind of new law that could be made the nest time an envelope-pushing Establishment Clause case comes to the Supreme Court:

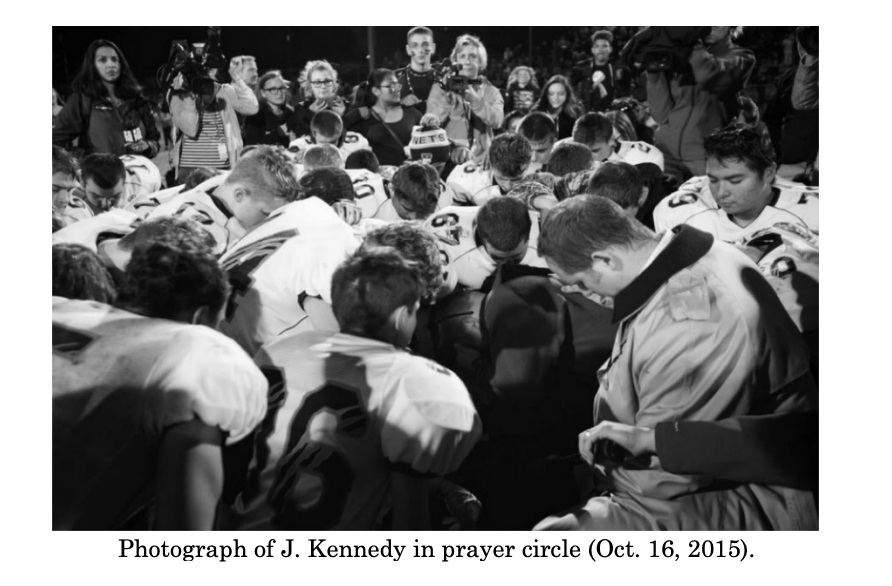

Bremerton is a mystifying decision, in part because the six Republican-appointed justices in the majority took great liberties with the case’s facts. It involved a high school football coach who would pray at the 50-yard line following games — in full view of students, players, and spectators, and sometimes surrounded by many of them as he was praying. There are photographs of crowds surrounding this coach as he prayed, some of which were included in Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent.

Yet Justice Neil Gorsuch, who wrote the Court’s opinion, falsely claimed that this coach only wanted to offer a “short, private, personal prayer.”

Because Gorsuch lied about the facts of this case, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly what Bremerton held. No one questions that a public school employee may say private prayers while they are on the job. The question the Court was supposed to answer in Bremerton is whether a representative of the government may, during a public event, ostentatiously convey a religious message to hundreds or thousands of spectators — including potentially players who are under that government employee’s direct authority.

One thing that is clear, however, is that the ban on government endorsements of religion will no longer be enforced by this Court’s GOP-appointed majority. Instead of applying “the endorsement test,” Gorsuch wrote, “the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by ‘reference to historical practices and understandings.’”

And what, exactly, are those “historical practices and understandings?” Gorsuch does concede that “government may not, consistent with a historically sensitive understanding of the Establishment Clause, ‘make a religious observance compulsory.’” But his opinion suggests that the clause may do nothing else.

Among other things, Gorsuch cites favorably to Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent in Lee, which described Justice Kennedy’s concerns about subtle pressure on public school students as “precious,” and which declares outright that “the coercion that was a hallmark of historical establishments of religion was coercion of religious orthodoxy and of financial support by force of law and threat of penalty.” Gorsuch also quotes James Madison, claiming that Madison understood the First Amendment “to prevent one or multiple sects from ‘establish[ing] a religion to which they would compel others to conform.’”

So, while the Bremerton opinion is not a model of clarity, two lessons can be extracted from it. One is that the ban on government endorsements of religion — the mechanism the Court used to ensure that a plurality of faiths would thrive in the United States — is now dead. The other is that, while the Court still recognizes that some forms of government coercion into religious behavior are not allowed, its Republican majority appears eager to narrow the definition of “coercion.” There may even be five votes for Scalia’s position — that the government may actively promote religion so long as it does not use force or the threat of penalty to do so.

Speaking of Oklahoma, its schools superintendent is proposing stuff like hanging the Ten Commandments in classrooms. If he goes through with it, it is frighteningly likely that the Supreme Court would use this as a vehicle to overrule McCreary County.

…As dneus correctly observes in comments, as atrocious as Bremerton was on multiple levels, the real canary in the coal mine was the opinion written by Reasonable, Moderate, Thinking Person’s reactionary John Roberts in Espionza v. Montana, which effectively ruled that the Establishment Clause violates the Free Exercise clause.