Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,153

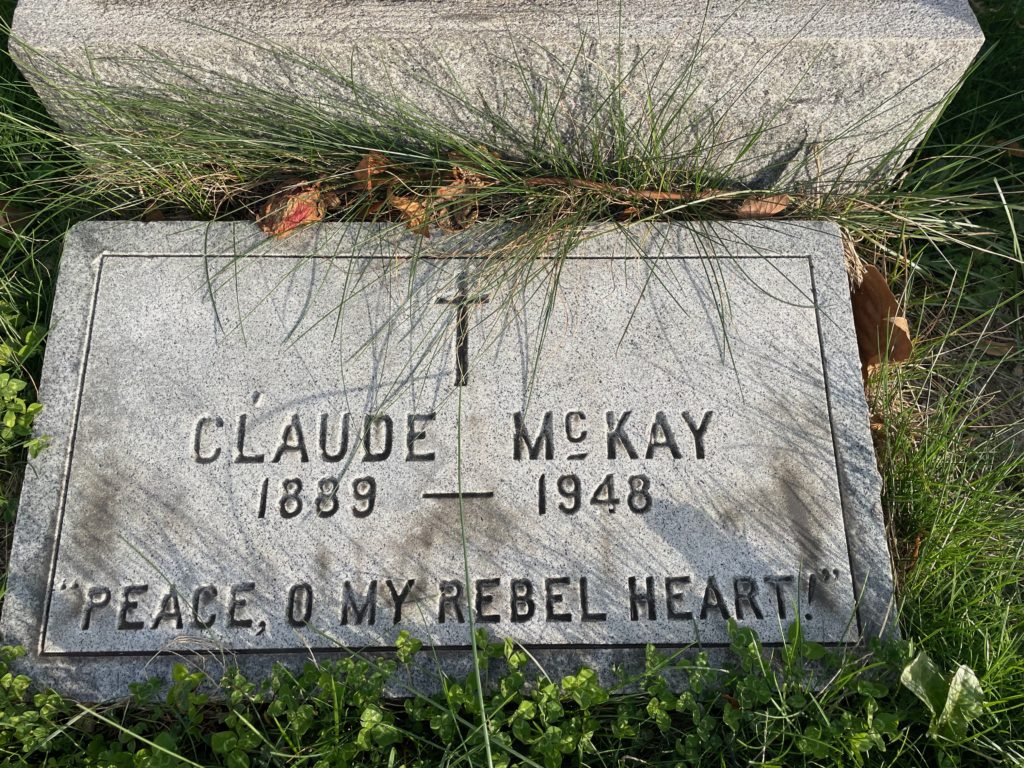

This is the grave of Claude McKay.

Born in 1889 (some say 1890) in Clarendon Parish, Jamaica, McKay’s writing talent was quickly realized, even though his parents were just farmers. By the time he was only 10, he was already a locally recognized poet. This got the attention of a white man named Walter Jekyll. He encouraged the young boy, though he encouraged to write in dialect specifically, which is always difficult to deal with today. By 1912, he had already published two volumes of dialect poetry in Jamaica.

McKay first came to the U.S. to attend college. That was at Tuskegee, Booker T. Washington’s legendary though problematic institution in Alabama. While in college, he read DuBois’ brilliant The Souls of Black Folk (I’d argue this is the best nonfiction book in American history). This really changed his life. He became interested in moving forward not just as an intellectual but as a political figure. McKay was also shocked at the racism he saw in Alabama. The English colony of Jamaica was no paradise, but Alabama was just a totally different deal.

McKay moved to New York in 1914 and soon became involved in the early days of the Harlem Renaissance. Fundamentally, he was a poet, though he would write in nearly every form. He first came to significant attention with his 1919 poem “If We Must Die,” in which he expressed his absolute outrage over the treatment of returning Black soldiers from World War I, many of whom were attacked and even lynched while still wearing their Army uniform. He saw some of this himself, while he was supporting himself for awhile working for the Pennsylvania Railroad. Let’s read it:

If we must die, let it be not like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursed lot.

If we must die, O let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave

And for their thousand blows deal one deathblow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

This has remained influential. In fact, the Attica rebels read it during the prison uprising in 1971.

McKay also remained a strongly political figure. He was a socialist, though more of the small “s” type, much more attracted to the syndicalism of the IWW than he was to the Communist Party. In fact, he was a Wobbly for a time, signing up in 1919. For awhile, he was co-editor of The Liberator, but there, his more fluid socialism caused all sorts of problems, especially with Mike Gold, who was a hardcore communist and didn’t care for a lot of what McKay published. But it’s not as if McKay was somehow opposed to the Communist Party, especially in its early days. In 1922, he was invited to the Soviet Union to attend the International. Like a lot of leftist intellectuals, he was at minimum highly curious and hoping to see a revolutionary model for the future. For the Soviets, he was a big get. They really wanted to convert him to the cause fully, hoping to have a Black leader in the United States. So they gave him the red carpet treatment. At first, he was pretty open to this. In fact, he wrote two books while in the Soviet Union about race relations in the America. The Negroes of America, published in 1923, analyzed American racism through a Marxist lens. Trial by Lynching, was, well about lynching.

However, McKay was not a dupe. It didn’t take him a real long time to realize that he was being played. The growing authoritarianism of the Soviets did not much appeal to a person like McKay. So he left in 1923. But he didn’t come back to the U.S. He needed more time away from this racist cesspool of a nation. So he spend the next decade in western Europe, mostly France, though also spending time in Hamburg and in Morocco. There, he felt a lot more accepted than he ever did in the U.S. While in France, McKay published extensively on his experiences in the United States. For example, in Home to Harlem, published in 1928, he wrote about the acceptance of gay people in that scene, both men and women. This was pretty frank talk for 1928. McKay himself was bisexual and was quite frank about that too. While this is a tremendously important and influential book, it was hardly praised universally at the time. W.E.B. DuBois, who really was the king of the snobbish uplift politics at this point in his life, was outraged that such a filthy book existed, one that he thought would give whites a bad view of the race. To quote the man, “Home to Harlem… for the most part nauseates me, and after the dirtier parts of its filth I feel distinctly like taking a bath.” But what McKay really accomplished here was a view into one of the most experimental and important cultural scenes in American history, one that demonstrated clearly the freedom it represented.

Home to Harlem was one of McKay’s five novels published in his life time. Two more have been published in recent years after being lost. In fact, one was just recently discovered in the archival collections of a different person, was verified as authentic, and published in 2017. Banjo came out in 1929 and attacked French colonial racism, becoming an early influence on anti-colonial literature that would come out of the global south a few decades later. Banana Bottom in 1933 explored what it meant to be a Black person in a white-dominated society. He returned to his Harlem explorations in his 1940 non-fiction book Harlem: A Negro Metropolis. In his 1937 book, A Long Way from Home, he explored his Moroccan travels for an audience that knew basically nothing about the place.

Finally, in 1934, McKay felt it was time to return home. This was at the peak of communist influence in the Black community. Who else was doing anything for the deep poverty in Black Harlem? No one. McKay immediately re-immersed in the community. But as a now committed anti-Stalinist, this meant immediate conflicts with the increasingly doctrinaire communists. He wrote extensively about this, but over time, he fell out of favor for political reasons. He did get a job with the Federal Writers Project in 1936, that great project which saved so many artists from poverty, at least for awhile. We should have this today for artists and not through the incredibly competitive and almost impossible to win National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, as great as the NEA is. We need more government support for artists. While writing for the FWP, he really began to explore his anti-communism in length, only isolating him further from the left, which thought he was a traitor, especially considering he had been to Paradise, i.e., the USSR.

By the 1940s, McKay was actually quite impoverished despite his decades of great work and the influence he had on American letters and life. He finally was rescued from his extreme poverty by a friend who was in the Catholic Worker movement and placed into a communal living situation the church ran. For this, he converted to Catholicism and worked mostly on Catholic social charity issues in his later years.

McKay died in 1948 in Chicago. He was 57 years old.

Claude McKay is buried in Calvary Cemetery, Queens, New York.

The Library of America does not have a single volume dedicated to McKay (they should, though there could be rights issues at play; now that the ridiculously long copyrights are passing, LOA is producing volumes of great writers they could never get the rights to, at least for their work in the 20s and of course the possibilities expand every year. But Home to Harlem is part of the LOA collection of Harlem Renaissance novels. If you would like this series to visit other authors represented in this collection, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. So far in the month of July, I have received…..$15. So this series may conclude once I get through this set of graves. Let’s hope not. Up to you all though. Jessie Redmon Fauset is in Collingdale, Pennsylvania and Wallace Thurman is in Staten Island. Previous posts in this series are archived here.