Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,018

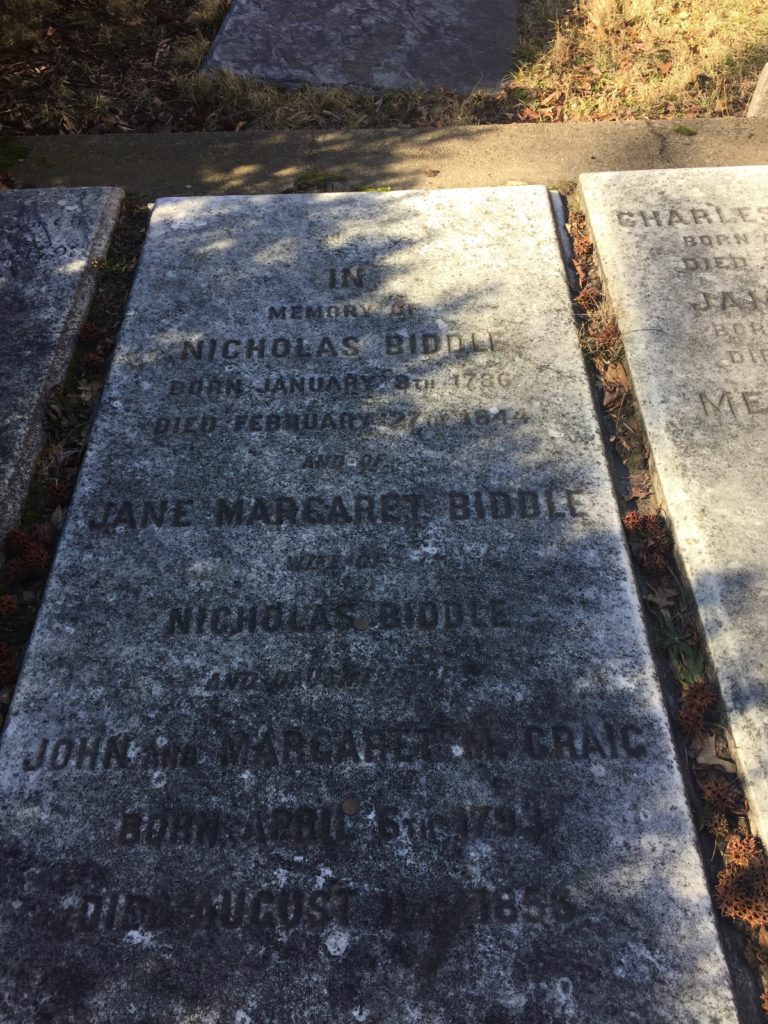

This is the grave of Nicholas Biddle.

Born in 1786 in Philadelphia, Biddle grew up in the elite of the Early Republic. He started college at the University of Pennsylvania in 1799, but was considered too young to graduate so he transferred to Princeton, where he graduated in 1801. That’s right, he was 15 years old. He was also valedictorian. He started studying for the law, but was offered the position of secretary to John Armstrong, who was a New York senator and leading foreign policy figure of the period. This meant Biddle was in Paris during the aftermath of the Louisiana Purchase. He worked on the details of the land transfer, and then was James Monroe‘s secretary, who was then minister to England. He spent a lot of time in Greece and learned the language, becoming something of an expert on the differences between classical and modern Greek.

In 1807, Biddle went back to Philadelphia and started practicing the law. He wrote a bunch about the arts during these years and helped run an influential early literary magazine that lasted nearly twenty years, a lifetime in those days of magazines. When Lewis and Clark returned from their journey to the West, it was Biddle who edited the diaries for publication, though he had to give up the end of that when he was elected to the Pennsylvania legislature in 1810. He served a term there and then a term in the state senate. He was an early advocate for the common school system that would later become the standard in American public education.

Biddle was known among the nation’s elite, but he didn’t gain larger attention until he began to defend the Bank of the United States. James Madison did not want to recharter it, but Biddle advocated for him to do so. He became well known for his writings on the subject and made John Marshall a big fan of his. What Biddle and Marshall had in common, though nominally in different political parties at this time, was a belief in a strong centralized nationalism revolving around the nascent system of financial capitalism being created at this time. Strong banking was central to this vision and so was a strong state to implement the vision. Madison, not being an idiot, decided to recreate the BUS at the end of his term and then Monroe named Biddle its director, rising to president in 1822.

Now, the financial system of the U.S. was a complete disaster at this time. The states could issue currency and because of this, counterfeiters operated in the open. A dollar issued in Rhode Island might be worth 95 cents in Connecticut, 80 cents in New York, and 20 cents in Georgia. Biddle tried to rein in some of the worst excesses of this system. He attempted to controlled the national monetary supply and set interest rates, key parts of what the Federal Reserve does today. Given that the nation’s most important product was cotton, he used the BUS to help facilitate cotton production (little evidence Biddle cared at all about the lives of slaves) and moved resources to the West. Of course, this did not endear him to people such as Andrew Jackson, who were deeply suspicious of anything to do with banking or financial capitalism. Biddle was pretty successful though at stabilizing American capitalism and providing an atmosphere where the British felt comfortable investing, which was important in a nation that still had a quite small economy.

Biddle held his job through the John Quincy Adams administration, who most certainly supported a strong government and centralizing banking. Then Jackson took over. The details of the Bank War between Jackson and Biddle are pretty well known, but let me make a couple of points. Of course, Jackson was a nearly complete ignoramus when it came to economics, even as his own plantations benefited from Biddle’s actions. But you know, Biddle really was a condescending snob. He was an elite’s elite. Concerns about the Bank’s friends personally benefiting from Biddle’s actions were real enough. Moreover, Jackson believed that branches of the BUS had actively helped Adams in the 1828 election, though there’s little evidence this is really true. But certainly the bankers involved did want Adams. After all, he understood what they were trying to do. So Jackson vetoed the renewal of the BUS charter in 1832. Biddle was shocked. How could Jackson be so petty and so stupid? Well, Biddle had a response–this time he was going to use the full resources of the BUS to try and defeat Jackson that fall, going all in for Henry Clay. This did not help the situation. Politicizing the Bank even more, not to mention spending its money for Clay, and then not winning really did doom it. Jackson had actually directly warned Biddle not to do this. When he did, it just opened the Bank and Biddle up to attacks that it was an institution that was enriching the wealthy elite, who were Biddle’s friends, at the expense of the average man. This had the added virtue of being mostly true. Even if Biddle was right about the overall economy, Jackson was mostly right about Biddle himself.

In the aftermath, Jackson engaged in an even stupider policy, withdrawing federal deposits and giving them to the state banks, which were run in an absurdly irresponsible manner and which would lay the groundwork for the Panic of 1837. Biddle tried to respond by raising interest rates to tank the economy and then blame it on Jackson. It worked a little bit. The economy dipped in 1833-34, but it did not have desired effect of forcing Jackson’s hand. A majority of Congress did in fact support the BUS. But not the 2/3 needed to override the veto. So….Biddle was out of luck.

Biddle convinced the Pennsylvania state legislature to continue the bank as a state-chartered institution in 1836. It was in these years that Biddle went all in on cotton, investing very heavily in the profits from slavery, even though the bank’s charter did not really suggest this was legal. He really started engaging in the same questionable speculation that he had previously advised against. That blew up in 1839, when he was forced to resign after overextending the bank on its cotton investments. The bank itself failed in 1841. As it turned out, Biddle and friends had personally borrowed money from the bank, which was kinda sorta against the law. Of course all this was gold to Jackson and his cronies, for whom this demonstrated that all the corruption they laid at Biddle’s feet was true. He was arrested in 1841 and forced to use what was left of his money to pay back the bank’s creditors. Biddle died in 1844, at the age of 58, on his large estate outside of Philadelphia. Luckily for him, he had married very rich and his wife’s fortune kept the family going in these last years.

Nicholas Biddle is buried in Saint Peter’s Episcopal Churchyard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

If you would like this series to visit other leading American bankers, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. A.P. Giannini is in Colma, California and Thomas Lamont is in Englewood, New Jersey. Previous posts in this series are archived here.