Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 851

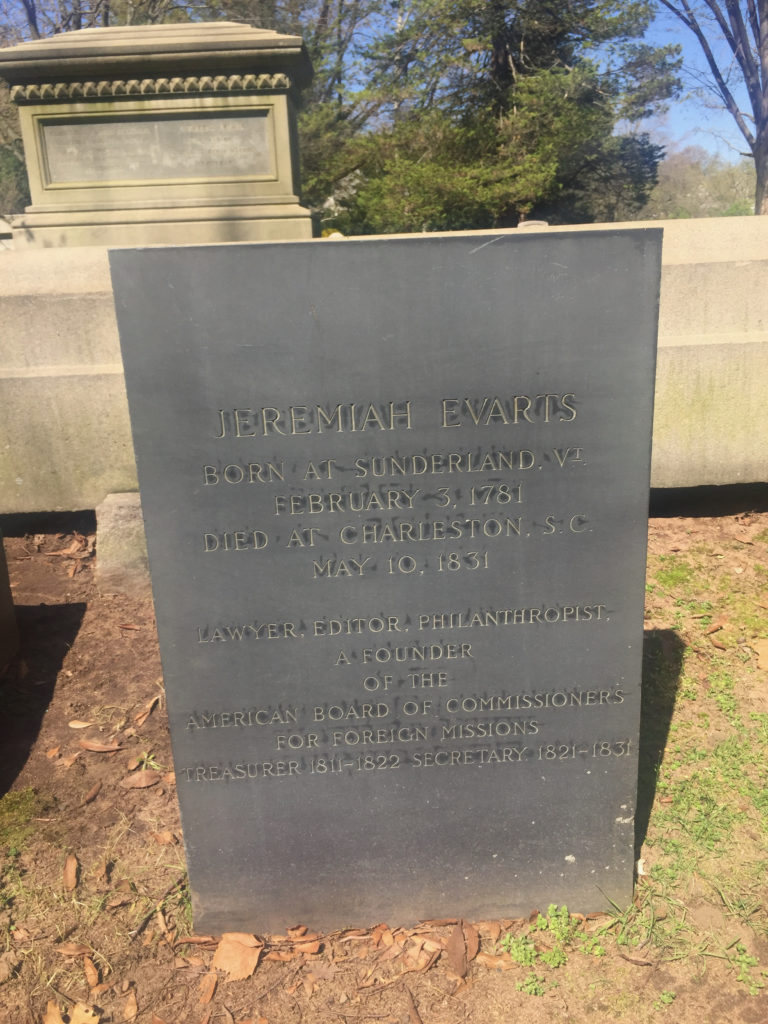

This is the grave of Jeremiah Evarts.

Born in 1781 in Sunderland, Vermont, Evarts grew up in a farming family. His father owned a good bit of land in Vermont but was not particularly wealthy, which made is somewhat surprising that he went to Yale and graduated in 1802. His parents hoped he would return to Vermont and become a leader there, but he was firmly a man of a more urban New England. He had undergone a conversion experience that Timothy Dwight led at Yale and he wanted to return to that world. So after a brief return home to run a school, he came back to Connecticut. He became a member of the Connecticut elite, passing the bar in 1806 and then marrying Roger Sherman’s daughter. As a lawyer, he was pretty whatever, not having a lot of passion for it and preferring the life of the mind and the life of social activism. From a young age, Evarts was interested in missionary work. He very much imbibed the liberal Protestantism of his place and time, a precursor to the Second Great Awakening. He got involved with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, taking over as its secretary in 1811 and then its president in 1821. He also wrote heavily for religious magazines. As the editor of The Panoplist, the leading Congregationalist journal of the time, which he took over in 1810, he wrote over 200 articles promoting his vision of a liberal Christianity.

As a religious liberal reformer, Evarts primary interest was Indian rights. He became the single most prominent white opposing Cherokee Removal. Twenty-four of his essays were in defense of Indian rights, written under the pen name of “William Penn.” This makes him one of the good guys compared to Andrew Jackson. Well, I guess. See, the thing about even a guy like Evarts is that one of the most liberal men in America on this issue still had absolutely no tolerance for Indian culture as it was. His position was that the Indians could be civilized and Christianized. We didn’t need to evict them. Instead, we could remake them as white Christians. So he was absolutely not supportive of anything such as Indian sovereignty or religion or hunting practices or gender roles. He was supportive of sending large amounts of missions and money to the tribes in order to whiten themselves. Evarts and his missionaries frequently used terms such as “heathens” and “savages” to describe Native Americans. This is as good as it got among American whites.

And still, such an extremely limited position in favor of Indian rights still outraged the majority of whites who wanted the tribes completely exterminated, or at the very least removed. One of the things we often overlook when focusing on Andrew Jackson’s horrible actions around Indian Removal is that Georgia whites were perfectly happy just entering into Cherokee country and killing whoever they saw. The only way around this might have been to use the American military to kick out any whites and prosecute those who killed Indians, but this basically puts us in an entirely different nation that did not exist. After all, many of the starkest abolitionists engaged in their own personal slaughter of Native peoples, whether John Chivington or John C. Fremont. For Evarts, what removal was really about was the decline of Christian values in America and he was horrified that Baptists in Georgia would support such anti-Christian actions, or even worse, that Methodist missionaries had actively supported Choctaw removal.

But at the very least, Evarts concern for kicking the Cherokee and other southeastern tribes off their lands was truly felt. He led the lobbying efforts against the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and continued to fight against removal after this. Georgia’s response was to pass a law banning any white into Cherokee lands without getting a license from the state first. That might sound like progress, but this law was intentionally designed so that missionaries associated with Evarts could not enter Cherokee lands and help them resist white domination. Evarts was working closely enough with the Cherokees that he encouraged them to put their faith in the American justice system and seek redress that way, which led to Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, among other cases. He encouraged missionaries to break these laws and go to prison, believing that a social movement would soon free them.

Like most of these reformers, Evarts had lots of other interests as well, particularly the temperance movement. He also believed that Jacksonian America was a disaster, with the spirit of entrepreneurial capitalism and crass politics destroying the New England values that he believed were at the nation’s core. He saw Andrew Jackson and his supporters and believed that a cancer was at the heart of the nation: selfish individualism. Most certainly he was not only person who believed New England was vastly superior to the rest of the nation and bemoaned no one else outside of it caring about the region. But as an optimist, he refused to believe that the nation was doomed and rather needed a revivalist spirit to set itself back on track.

But Evarts did not survive to see what would eventually happen to the Cherokee. He died of tuberculosis in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1831. He was 50 years old. The reason he died in Charleston is that his illness had advanced and he hoped to regain his health through a long trip to Havana. He health had been poor for most of his adult life. He stopped in Charleston to meet with people about fighting Cherokee removal. But he never left.

Jeremiah Evarts is buried in Grove Street Cemetery, New Haven, Connecticut.

If you would like this series to visit other people involved in the Cherokee removal issue, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. John Ross, the Cherokee leader in the anti-removal movement, is in Park Hill, Oklahoma and Elizur Butler, one of Evarts’ missionaries who refused to leave prison when Georgia tried to pardon all the missionaries they had imprisoned, is in Van Buren, Arkansas. Previous posts in this series are archived here.