What does it mean to say that international order is becoming more “illiberal”‘

Alex Cooley and I published a piece at Foreign Affairs which discusses how international order is becoming more or less “liberal” across three dimensions: political rights, economic arrangements, and forms of international cooperation.

f current trends continue, the emerging international order will likely still contain liberal characteristics. Liberal intergovernmentalism—in the form of multilateral organizations and interstate relations—will remain a major force in world politics. But this will be, to adapt a cliché, intergovernmentalism with autocratic characteristics. Authoritarian states will continue to chip away at political liberalism in older international institutions while constructing illiberal alternatives. Transnational civil society will likely remain a site of continuing ideological contention, with a variety of reactionary, populist, and pro-autocratic actors competing with liberal groups and one another. Such a world will more closely resemble that of the 1920s than the Cold War. Even a “return” to what the Trump administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy called “great power competition” is just as likely to spur on illiberal tendencies—including animus directed at ethnic Chinese and pressure to expand domestic surveillance—as it is to reenergize liberal advocates, institutions, and networks.

Barring unexpected changes in the distribution of power or regime change within rising authoritarian states, defenders of international political liberalism should not expect more than intermittent success in holding the line. One important step, though, would be a coordinated effort by major democracies to engage with new regional organizations on common issues and norms and values—that is, concerns that usually get bracketed in the name of political pragmatism. Comprehensive engagement should become the standard way for liberal states to interact with groups such as the SCO, the CSTO, and the Eurasian Economic Union.

Most of all, democratic powers need to show up and push for their values. Trump’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization illustrates the risks of doing otherwise. After the Trump administration withheld its funding to protest Beijing’s alleged undue influence, China announced that it would step in to bridge the subsequent funding gap. Rather than confront China’s revisionism, such withdrawals concede new areas of global governance to Beijing and its illiberal clients. Here, the Biden administration’s declared intention to embrace multilateralism is a welcome development.

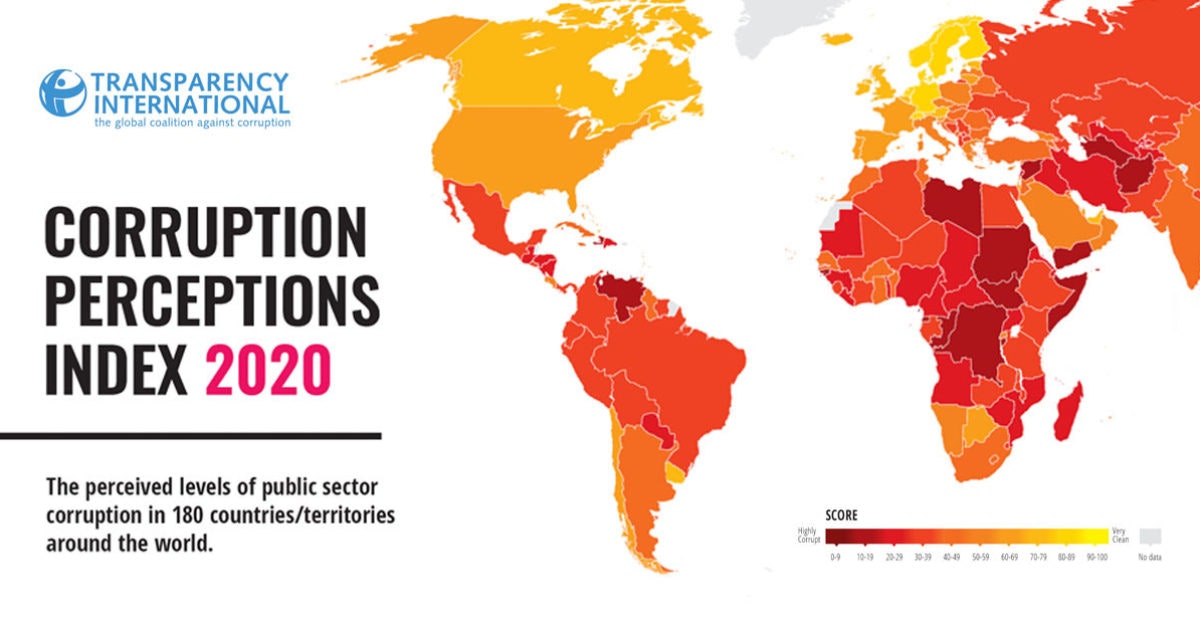

We point out that while a strong anti-corruption agenda is important to protecting liberal democracy – both at home and abroad – it has downside risks, including threatening regimes that the U.S. already has tense relationships with. Moreover, it’s a big mistake to ‘externalize’ the problem when the U.S. is one of its key drivers:

The United States has done much to make economic liberalism friendly to corruption. In its 2020 Financial Secrecy Index, the anticorruption watchdog Tax Justice Network ranked the United States as the second “most complicit” country in the world, right behind the Cayman Islands, when it came to enabling money laundering by criminals and wealthy individuals. Combined with the rise of unregulated and opaque dark money flooding into the U.S. political system after the Citizens United Supreme Court decision, shell companies have become the primary vehicle through which corporations and wealthy individuals avoid taxation and directly influence the political system and campaigns.

…. The U.S. Corporate Transparency Act of 2021—which ends the anonymity of many shell corporations by 2022—is a major step in the right direction. But Washington, London, and Brussels should do much more to harmonize their efforts, including creating common and public registries of beneficial owners of companies and enacting coordinated sanctions on kleptocrats.

If you can, check it out.