Higher Education and the Economics of Pandemic

The malign incompetence of the Trump administration has already, by some estimates, killed at least 100,000 Americans. The US has failed to contain the pandemic, and CDC officials are increasingly pessimistic about where the country is headed. Our “test and trace” capabilities – that is, the very capabilities that were supposed to enable the country to reopen – are woefully inadequate. And, of course, too many politicians and citizens refuse to take the pandemic seriously.

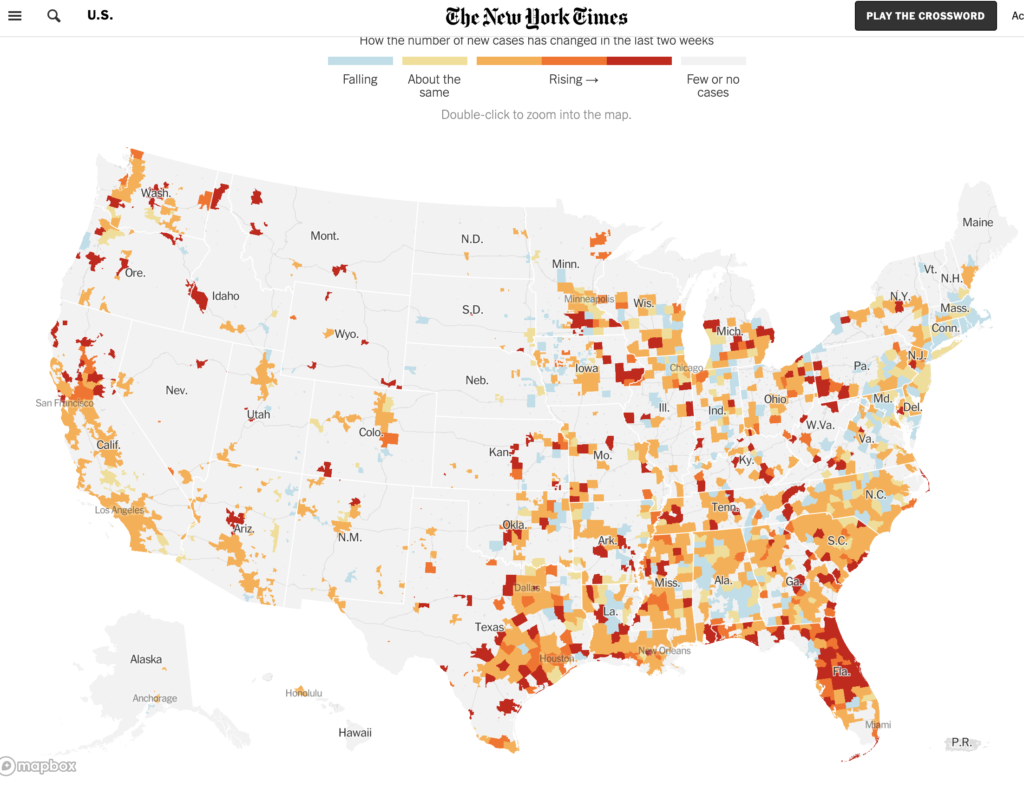

The result is topography that, even considering increased testing, does not exactly inspire confidence. Parts of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic have, for now, gotten things under control. Not so most of the rest of the country.

This means, as I’m sure you are all aware, businesses and organizations throughout the country are faced with an impossible choice, and the economy is quite possibly in even worse trouble than it was during the lockdown.

Higher education is no exception. Most colleges and universities are desperate to get students back on campus. They need the housing fees. They also worry that students won’t enroll – or, at least, will enroll at much lower rates – if their only choice is to take courses online.

Let’s be clear, a lot of institutions are looking at financial armageddon. At least one school has already laid off tenured faculty – although that may have been more opportunism than financial necessity. Even wealthy universities have frozen hiring.

As Susan Dynarski argues in The New York Times.

Students typically move into crowded housing and reconnect with friends at parties, mixers and bars. When classes start, they customarily file into large lecture halls and small seminar rooms, sitting close together, heads bent over books and laptops.

This is a joyful scene in most years. In a pandemic it would be an epidemiological nightmare.

Colleges will have to look very different this fall if they are to avoid accelerating the pandemic. But financial and political pressures are forcing many schools to make choices involving difficult trade-offs between their students’ education, public health and their own economic well-being.

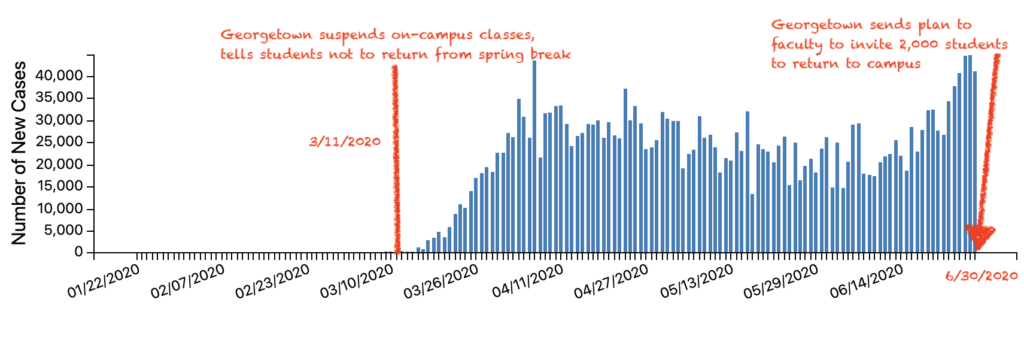

Colleges were among the first institutions to respond when much of the world went into lockdown this spring: Campuses closed, and students finished their interrupted semesters online. Now, college administrators are pondering how they will reboot this fall.

Here’s a scarily plausible chain of events. Colleges bring students back to campus — where they act like college students. They meet over coffee, go to parties and bars, pair off on dates and congregate in crowded dorms. The virus quickly spreads among students, who mostly recover quickly or are entirely asymptomatic.

But soon the virus reaches the older, more vulnerable members of the faculty and staff, as well as local residents. Infections surge. Teaching hospitals care for the ill at the larger universities, but small, regional hospitals near rural colleges are quickly overwhelmed.

Keep in mind that while rates of death and severe complications are lower among young adults, it’s still dangerous for 18-22 year olds (and not all students, especially outside of elite schools and four-year programs, are that young).

So we’ve got a race between further financial calamity and public health considerations. Many schools are trying to split the difference by letting some students back onto campus – and not just those who have no other good options, which isn’t terribly controversial – while mandating social distancing, equipping classrooms with protective measures, and taking other measures to limit contagion. This means, in practice, that you might have 19 students in a classroom that normally holds 90. Many classrooms won’t be usable at all.

This approach requires running “hybrid” classes in which some students are in the room and others are watching (and participating) via the internet. So professors are now supposed to design classes that meet best practices for distance learning – such as lots of asynchronous content – but that also integrate on-campus students. My sense is that this is… pedagogically problematic. I’m pretty sure that it’s better to design a class that’s entirely online than to mix and match.

Beyond pedagogical concerns, though, I’m just not seeing how any of this works. The current pandemic environment is worse – especially for institutions that draw people from across the country – than the one that prompted schools to shut down in the first place. Ye here we are.

Maybe we get lucky and it turns out that the worst – in terms of, say, the death rate from the disease – is behind us. Maybe colleges and universities don’t spend a bunch of money on protective measures only to have to send students back home in October. Maybe 18-22 year olds will actually alter their behavior.

Or maybe this is a huge mistake foisted upon us by the total and abject failure of the Federal Government.