Organized Labor and COVID-19: A Conversation

This post is a conversation between myself and Patrick Crowley, Secretary-Treasurer of the Rhode Island AFL-CIO and staffer for the National Education Association-Rhode Island, about organized labor and the response to COVID-19.

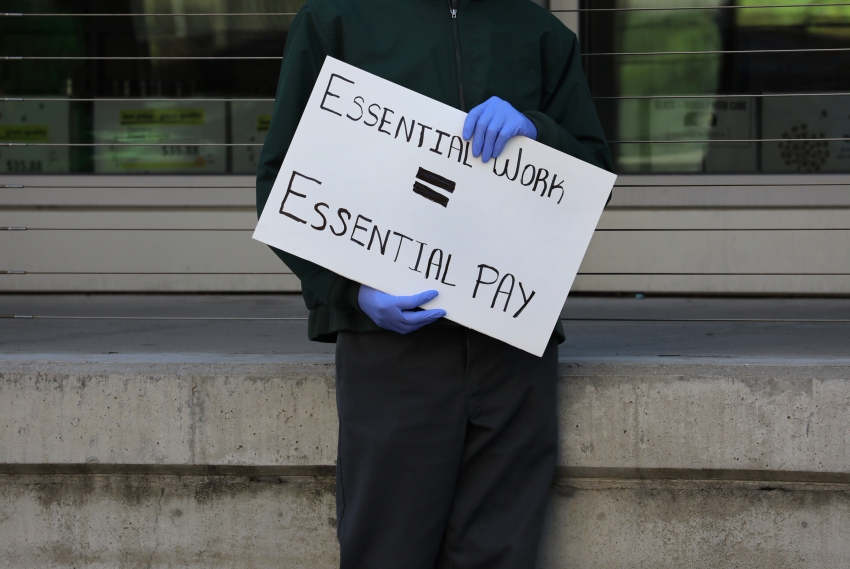

EL: The first bailout provided at least some workers with $1200 per person. But that’s far less than is needed for people to survive when they are not working. What does organized labor think the next bailout should entail?

PC: You’re right, but that’s not all it did. On the positive side, and one I wish got more attention, are provisions protecting collective bargaining and actually encourage union organizing. Section 4003 of the CARES Act says that for loans to mid sized companies from the Fed, that is between 500 and 10,000 workers, “The borrower will not abrogate existing collective bargaining agreements for the loan duration and for two years after completing loan repayment, and will remain neutral in any union organizing effort for the loan duration.” I’m not claiming that this provision is a 21st Century Section 7A of the National Industrial Recovery Act, but it is something, and the next package should have more like it.

On the negative side, as Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse has highlighted, the CARES Act created a loophole for certain millionaires giving them a massive tax cut. In the next package, we need to make sure we don’t have any more of this.

In other words, the next bailout needs to be much more worker centered.

There should be a 100% federal subsidy for cobra payments for workers who lose their employer based health insurance.

Congress needs to mandate OSHA issue emergency standards protecting all workers from infectious disease.

If there are any payments or loans to employers, it must be contingent on keeping people on the payroll and making employers continue to pay into pension plans and health and welfare funds.

There needs to be direct and substantial payments to state and local governments to make up for lost tax revenue, keeping public schools, public higher education, and other state services open and employing workers.

And finally, there needs to be money to finally start rebuilding our infrastructure. Here in Rhode Island, there is a real concern that the private construction market will simply dry up – so the federal government needs to step in. Rhode Island voters passed a substantial bond measure in 2018 to rebuild Rhode Island’s crumbling public schools. The Feds need to make sure that those projects and more like them move forward.

Those might be heavy lifts given the make up of Congress, but in reality, these are just minimum steps.

EL: The media rarely if ever reports on how organized labor fights in Congress for a better life for working people. What is the American labor movement generally and the Rhode Island labor movement specifically doing to place these issues at the top of politicians’ agendas? And how are they responding to the needs of labor in this terrible time?

PC: I’ve got to give the national AFL-CIO credit for working to get the message out, despite the obstacles of dealing with the corporate media. President Trumka has been featured in a number of interviews on CNBC, Fox Business News, and affiliated organizations like the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement (LCLAA) are using social media and other channels to raise the alarm about how the virus is attacking minority communities at disproportionate rates. The AFL-CIO is sending out daily briefs that I would encourage your readers to sign up for.

Here in Rhode Island, the state federation has been holding conference calls for local labor leaders every other day so our leaders, many of whom are still rank-n-file workers, can ask questions of the state’s political leaders. We’ve had Governor Raimondo join us twice, the State Treasurer, the Attorney General, the Secretary of State, the Senate President and our entire congressional delegation. Our leaders have been able to ask questions, sometimes pretty tough ones, about what steps the government has taken to address the crisis. It’s also been a chance to triage problems that have come up for our members. For example, in the early days of the crisis, there was a real concern that one of our hospital chains was going to start furloughing front line health care workers because they were hemorrhaging money after elective procedures were cancelled, cutting off a significant revenue stream. As a result of these calls, labor leaders were able to convince political leaders to investigate so folks could keep working.

Similarly, there is a non-union food processing plant in Rhode Island that some of our activists have been in contact with before the crisis hit. The company was not responding appropriately to social distancing guidelines so the activists were able to use the local media to help bring attention to the situation.

EL: One thing we are seeing in Rhode Island and around the nation is that low-income workers, often people of color, have far higher rates of exposure to COVID-19 than the wealthy. In Rhode Island, a remarkable 45 percent of cases are in the Latino population, a group which makes up only 16 percent of the state. Given that the modern union movement is increasingly made up of people of color and that areas of growth in recent years have largely concentrated with these workers, what do you think this public health crisis says about the relationship between poverty and disease in the United States and how can the labor movement be a leader in creating a more equitable public health system in this nation?

PC: As your question came in via email I was on the phone with one of the unions representing nursing home workers here in Rhode Island. The union is increasingly concerned how the crisis is affecting their members in this industry right now – mostly women of color, many of whom are immigrants from Central America and Africa. One of their shop floor leaders was just placed in quarantine because of a suspected exposure to COVID-19.

SEIU 1199, prior to the crisis, was trying to get legislation passed that would establish a safe staffing ratio for nursing home workers. Rhode Island is the only New England state without a formal standard or law that mandates how many residents a nursing home worker can be responsible for caring for on a shift. After the crisis started, they didn’t let up, and released a report showing how the Rhode Island nursing home industry profits by overworking the employees and under serving the residents. We’ve taken part in several caravan rallies to try and get their workers PPE and hazard pay, with some success. There are more caravans scheduled for this week.

To me, this crisis shows how we have subsidized parts of middle class life by intentionally under paying certain groups of workers – workers labor reporter Sarah Jaffe describes as employed in “Care Work.” So if the labor movement is to be a leader, we need to make clear to the public that the relationship to disease and poverty is related to the gendered and racialized nature of care work. As a movement, we need to be intentional about organizing care workers. But one thing I hope that comes out of this is a real discussion about what that organizing looks like.

EL: Given the catastrophic nature of COVID-19 to our economy and to our sense of health and safety in a globalized world, what do you think that organizing might look like? What are the key lessons we need to learn from this crisis in terms of the economy, work, and organizing?

PC: I’d like to be positive and think that this will start to reorient our thinking towards seeing the essential nature of all workers but the reality is that is not going to happen in a country dominated by wealth and corrupted by corporate power. However, something I’ve seen in Rhode Island does give me hope. Union members in many different industries, but especially lower paid jobs like food service, and health care, are really starting to understand that their bosses truly do not give a damn if they live or die, and are fighting back, through their unions. Sure, it might be small steps….but it is progress.

Just before the crisis, we held a meeting at our office in Providence with a number of organizers from various unions in Rhode Island to start to think about organizing in a more coordinated way. We are at about 18% union density in the state, and we talked about setting an ambitious goal of getting us up to 25% and what would it take to get there. One lesson from the current crisis is that when we need to we can truly work together not as individual unions but as one movement. That spirit is going to need to continue.

I want to work towards a way were we are forming new unions from scratch – and create the space to be able to explore how to do that. The corporate class isn’t the only entity with the ability to act as incubators of new ideas. Some will fail, and spectacularly so. But our movement will grow larger and stronger with every attempt. I think it will be cool, and bring a lot of energy to our ranks, to see new unions grow from nothing into reality. I think we need to reconstruct some alliances between union organizers, academics, lawyers, in ways that explore what some next steps can and should look like. The labor movement looked different when I started as a grunt organizer 25 years ago than it does today and we need to be prepared for it to look very different 25 from years from now – but that doesn’t mean we can be intentional as well as experiential in what we do.