Corporatism, faculty governance, and workplace democracy

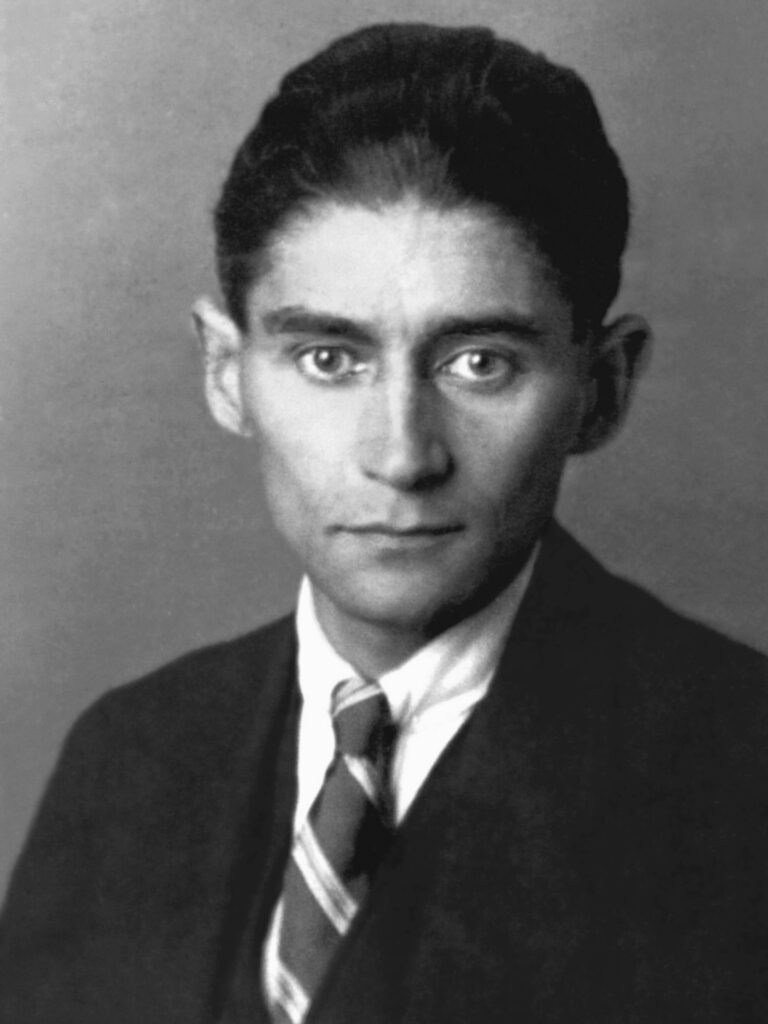

The top administrators at the University of Colorado are currently deciding whether to reappoint the dean of the law school to another five-year term. For reasons that will be obvious to faithful readers of this blog, I consider this question to be a Kafkaesque exercise in gaslighting, analogous in its own modest way to questions such as “Should Donald Trump be re-relected president of the United States, after all that stuff that happened?”

As part of this process, we (faculty, staff, some students and alumni) have been asked to fill out a 25-page human resources style survey, which is supposed to, in the jargon of that trade, “identify areas of strength and areas for growth.” I guess we should have probably done something like this as a nation before the 2024 election. Let’s see, areas of strength . . . I’m really struggling with this one. Areas for growth: fewer insurrections, extortion schemes, open thievery, and other impeachable offenses would be a good start.

Ah gallows pole humor. Anyway, my colleague Jennifer Hendricks, author of the extremely interesting recent book Essentially a Mother, which anyone who thinks about legal questions touching on pregnancy and motherhood should read, sent an email to the faculty this week, laying out in a particularly cogent way the implicit politics of this sort of process in the context of the contemporary university. She’s given me permission to post it here:

You may have seen that the agenda for Wednesday’s faculty meeting includes a “discussion of voting process” in connection with the decanal evaluation survey. As the person who asked that notice of a possible vote [regarding whether the dean should be reappointed] be placed on the May 2 agenda, I’m writing with some background thoughts that I’ve already shared with the decanal evaluation committee and the rules committee.

Of course, nothing prevents any faculty member from making a relevant motion at a faculty meeting. You might wonder, however, why I thought anyone would do so, given that we’ve all already been asked to answer a survey question about re-appointment of the dean. The short answer is that I believe the exercise of our faculty governance structure is importantly distinct from an opinion-gathering survey.

The longer answer is that we have three competing organizational models at play:

(1) corporate authoritarianism: A university is like a corporation, and the administrators are the corporate executives; appointment of a dean is a personal prerogative of the provost. This model is reflected in statements like “the provost should get to choose his team.” It is also associated with rationalist, social science approaches that cloak the exercise of that personal prerogative in a scientist mantle. This is [the provost’s] preferred model and the one presumed by the “survey” approach. It treats both faculty and staff as subordinate employees whose input is analogous to an HR focus group.

(2) faculty governance: The faculty is the governing body of a college or university. The faculty appoints administrators to tend to operations, including the supervision of staff (which proceeds under model 1). The provost’s role in appointing the dean is ministerial. This is the European model of the university, which was quasi-inherited by the U.S.

(3) workplace democracy: The entire workplace is understood as a site of democratic politics rather than corporate rationalism controlled by capital. All workers participate in governance through binding democratic mechanisms. As with faculty governance, the provost’s role in appointing a dean would be ministerial.

CU’s governance structure, like that of most American universities, is a mix of models 1 and 2. Our board of regents calls this mix “shared governance” among the faculty, administration, and board. (For some thoughts on how that came to be and on the balance among models 1, 2, and 3, see Kaufman-Osborn, “The Antidemocratic Legal Form of the University (and How to Fix It).)

In CU’s particular mix, department chairs are elected by faculty (model 2), while deans of schools and colleges have recently been treated as discretionary prerogatives with input from stakeholders (model 1). However, the law school dean is also the chair of the “department” that is co-extensive with the law school. Accordingly, it is particularly important for the appointment of the law school dean to incorporate model 2, especially since other faculty elect the primary administrators of their departments.

One problem with mixing model 1 with either model 2 or model 3 is that it’s easy for model 1 to co-opt models 2 and 3 with sham democratic structures that are re-characterized as “input” or “information” for the authoritarian decision-maker rather than as binding political acts.

For example, the evaluation survey is a model 1 approach, so I’ve invoked the faculty governance structure in an effort to incorporate an element of model 2, as in other departments and consistent with the regent policy of shared governance.

(More broadly, I think that the survival of universities as institutions with any credible claim to intellectual independence, which is essential to the defense of anything resembling a democratic society that protects human rights, depends on moving away from model 1 as quickly as possible. Re-creating academic administrators as “leaders” in the image of corporate executives is how we got the current situation at Columbia, the preemptive and historically tone-deaf renaming of CU’s DEI office as the “Office of Collaboration,” etc.)

I’m embarrassed to admit that, despite having spent a lot of time analyzing the finances of law schools in particular, and those of higher education more generally, I hadn’t until very recently thought much at all about the specific political arrangements that make the contemporary university workplace what it is, i.e., increasingly a reflection of the corporate authoritarianism model Prof. Hendricks describes here.

My recent institutional experiences have driven home how, if I might coin a phrase, the personal can actually be quite political when you think about it, which is why most people inside and outside the university seem to take great care to avoid making that particular mistake.