This Day in Labor History: March 30, 1891

On March 30, 1891, the National Union of Textile Workers formed. This early attempt to unite New England textile workers did not succeed, but it was an important moment in the struggle for worker dignity in this exploitative industry.

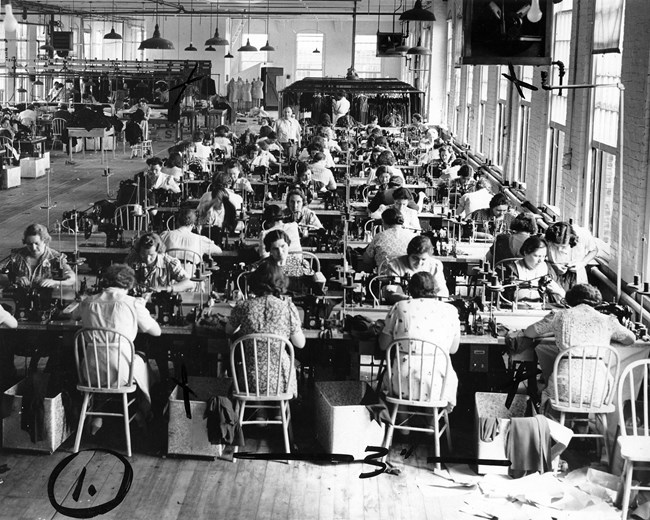

There were lots of strikes in New England mills going back to the Lowell Mill Girls and even before in New Jersey. But the problem was that workers were largely unorganized and there was little in the way of larger union activity that would bring them together. One problem is that opening a sweatshop was such a low capital investment that there were just so many of them. Easy to open, easy to close, easy to move–organizing the apparel industry has proved almost impossible even to the present. Even when there has been successful apparel organizing, and from the early 20th century in New York and Massachusetts to the late twentieth century in the South there has been, it rarely lasts long because it’s so easy for employers to avoid unions.

Part of the reason for the lack of successful strikes or unions were gender divides in the mills. It seems that most early strikers were women trying to increase their piece rates. But men held the higher paid positions and they rarely struck and rarely showed any kind of solidarity with the women. This meant that most strike assistance came from outside organizations such as socialist parties, rather than from a larger textile union. So what strikes there were often were lost among divided workers fairly quickly. But male workers have often chosen their masculine identity over their class identity, one of many ways the working class divides itself, then and now. This was a major issue in the 1882 Lawrence textile strike, for example.

At the end of March 1891, textile workers from around Massachusetts, as well as Rhode Island and New Hampshire, met in Lowell, Massachusetts, to form the National Union of Textile Workers. They wanted to work together as laborers from across the region on a series of specific goals, particularly wage increases and winning a 54 hour work week. They did not have a lot of strike success in their history. So they figured that a legislative route made more sense. They had some immediate success. Any kind of organization was going to have an appeal to desperate workers and so they won some significant support in towns such as Lawrence. There were even a few small, relatively successful strikes. The legislative path seemed to show promise because some of these workers had some experience in the Knights of Labor a few years earlier. They had won some actual victories, such as a bill to make it a requirement that Massachusetts employers pay their workers every week (imagine that!) and another for mandatory arbitration. This latter was especially significant precisely because it showed that these unions saw themselves very differently than American Federation of Labor craft unions, who opposed arbitration or any other government mandate or interference entirely.

These workers had some political support too. Labor was a real thing in late 19th century New England elections and candidates wanting their votes had to appeal to workers. They did so in a number of ways that intersected with the goals of these nascent unionists. That included ending the poll tax, a labor day of some kind (this would soon become federal law as a fairly meaningless sop to throw to the working class), the eight hour day for public sector workers, factory inspectors for women’s work, and other broad demands of the labor movement. So these workers did have political support from at least some representatives in Massachusetts and surrounding states. The culture of the Knights encouraged this greater political participation among members and even though that organization had fallen on pretty hard times by the early 1890s, the impact was still very real on workers and how they thought about their world.

Alas, this shortly ran into the Panic of 1893 and the general economic depression that followed, which put all the power back into the hands of the employers. In 1894, empowered, angry, and desperate Lawrence workers responded to a 25 percent wage cut by going on strike. But they were immediately replaced by other, even more desperate workers. The only workers these actions really ended up helping in the end were some of the more elite workers, mule spinners and loom fixers primarily, who won a few things. The Lawrence workers hung on to their strike for 84 days, but lost and 900 were permanently evicted from their mill. Still, the NUTW sort of held on and six months later, workers under their banner tried another strike, this time in Fall River. Though there was some good solidarity actions in the city around that, they lost too. It was just too much to overcome.

The revival of the national economy in the late 1890s led to another rapid expansion of the apparel industry. That it was so respondent to fluctuations in the economy though helps explain why it was so hard for workers to win unions. Plants could open and close so easily. The capital investment to buy a building and a bunch of sewing machines was so low that overcompetition was a very real problem, which afflicted other industries such as timber and coal. The factory managers also had almost inexhaustible supplies of labor, from various immigrant groups coming over from Europe and increasingly from French-Canadians too, who tended to be more suspicious of unions than the Irish or Jews. So average weekly wages for workers in Fall River, Lowell, and Lawrence were in fact no higher in 1911 than they had been when the NUTW formed in 1891.

This is just one story in the larger struggle for justice in the apparel industry. That would continue through the Uprising of the 20,000 in New York, the 1912 Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, other strikes in cities such as Fall River and New Bedford, etc. It continues today too, in the factories of Bangladesh and Cambodia and Sri Lanka.

I borrowed from David Montgomery’s classic, The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925, to write this post.

This is the 557th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.