This Day in Labor History: March 10, 1959

On March 10, 1959, loggers in Newfoundland organizing with the International Woodworkers of America got into a violent clash with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Newfoundland Constabulary. One cop died and the union lost the strike thanks to the machinations of Newfoundland premier Joey Smallwood.

The International Woodworkers of America was never a large union but they had quite a bit of power on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border in the Pacific Northwest. It was a true international, with Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia as its core membership sites. It was originally torn up by internal dissension over communism, which was more popular the farther north you went, so the Canadians were a lot more open to it than the Oregonians were. By the late 50s though, the IWA was mostly a left-liberal union with a strong record of pushing timber companies on bad environmental practices that could cost their members jobs if they did not engage in sustainable forestry, as I explored in my book Empire of Timber, though that focused on the U.S. side of the border. The IWA also wanted to expand. It never really created a secondary power base, but it had locals in the American South, the Great Lakes states, and Ontario and Quebec. Where it struggled to expand was into the maritime provinces.

There was a weak union in Newfoundland called the Newfoundland Loggers’ Association. The NLA simply did not have the membership or leadership to challenge corporate domination of the workforce. The IWA decided to enter the fray by going after the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Co., which was a big company. It was workers themselves who invited the union in, sick of the NLA’s weakness. That began in 1956. It had to poach from the NLA to do this, which was considered a big no-no in the labor movement, but which happened not infrequently anyway. The IWA thought it was worth it, especially given the weakness of that union.

Now, working conditions and especially workplace safety were pretty bad at this time. Logging has always been one of the most dangerous jobs you can do. Workers most certainly created masculine idealized work cultures around the danger, proud of what they could do in such conditions and sometimes actually opposing upgrades to worker safety when it interfered in their idealized culture. But in this case, there were some pretty upset workers ready to fight for better safety. Combine that with a demand for higher wages and you had workers ready to strike. They did, under the IWA banner, starting on December 31, 1958.

But not all the workers struck. Some were concerned by the leftism still dominant in the IWA leadership. Others held leadership positions in the NLA. Still others were fundamentally loyal to their bosses, an insane and nonsensical position to take at all times, but one that we can’t deny is really quite common among at least a solid minority of most workforces. So the strike was not just the IWA versus the AND. It was the IWA versus the AND and the NLA.

Moreover, AND executives were tight with Newfoundland provincial government officials. Joey Smallwood had been premier of Newfoundland since 1949 and he would remain so until 1972. He was also tight with the timber company executives. So he made sure the power of the state was starkly opposed to the IWA and he did so quite publicly. He was the kind of Cold War leader who was fundamentally conservative but understood the times in which he lived, so he combined a serious program of economic development, which in Newfoundland meant logging and hydroelectric power, with a support of large-scale welfare programs. Unions could have a place in that world, but only moderate unions that weren’t going to really challenge corporate domination. That was not the IWA.

Badger is a little town in central Newfoundland. It was totally dominated by the timber industry, supplying wood for the big mills in Grand Falls and still using old-school log drives, where timber was tossed into the rivers and driven downstream by water. This was a tremendously dangerous thing for the workers who had to break up log jams by walking on the water, placing bits of dynamite here and there, and hoping the whole thing didn’t shift while they were out there, throwing them under water and drowning or crushing them. Here, the cops were pretty much entirely on the side of the companies. There was a fight on March 10 that became known as the Badger Riot. That’s a bit overstated in that it wasn’t a “riot.” But a cop got killed.

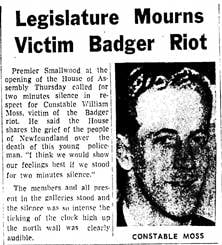

The death of a cop, even though said cop is doing what cops do, which is busting unions and protecting capital, turned the Newfoundland population against the IWA and the more aggressive unionism for which it was known. That led Smallwood to lead the Newfoundland government to pass a big number of new anti-striking laws that were flat out unionbusting, but which he had public support for now. Meanwhile, Smallwood started a new state-sponsored union called the Newfoundland Brotherhood of Wood Workers. The NBWW was precisely what the premier wanted–moderate, basically company oriented, and absolutely not tolerant at all of striking or anything that would get in the way of his developmentalist agenda. But as the IWA was losing the strike, workers started turning to it. The new “union” immediately signed a contract that gave the workers basically everything the IWA was negotiating for. That’s a common move for employers, giving workers all the material stuff they asked while giving up none of the power that is the real issue behind it all.

In short, the IWA not only lost the strike, but never again had a serious presence in Newfoundland. It would remain dominant in the western provinces and to some extent around the Great Lakes until the jobs started disappearing throughout the industry in the 1980s. It also remained stronger in Canada for longer than in the United States. In 1987, the Canadian side of the IWA broke with the failing US side and became the Industrial, Wood and Allied Workers of Canada. It remained independent until 2004. Finally, it merged with the United Steelworkers and its remnant unionized facilities remain with that union today. Meanwhile, Smallwood eventually handed the NBWW over to the United Brotherhood of Carpenters, the right-wing union that had long engaged in civil war over representing timber workers with the IWA. In fact, the IWA had formed because when the Northwest loggers unionized in 1935, the American Federation of Labor had given the loggers to the UBC, who did not give them full membership rights because they didn’t want a bunch of radical loggers having democracy. That led the IWA to split off in 1937 and a decade of near violence in the Northwest between the unions.

Ah, labor history. You think it is going to be the Good Workers against Evil Capital. It is not. It is filled with all kinds of stories of different workers hating each other more than hating the employers.

This is the 553rd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.