The Negotiations

Some thoughts on what seem to be initial negotiations to end this stage of the Russia-Ukraine War, both because it’s in the news and because we’re planning to run a large-scale negotiation simulation later this week on prospective cease-fire talks…

Things are not looking great right now, but I think it’s time to find some perspective on what negotiations might look like. I was not as alarmed as some by SecDef Hegseth’s comments about Ukrainian territorial integrity and Ukraine’s prospective membership in NATO. With respect to the first, the idea that Ukraine would regain all of its territory on either the battlefield or the negotiating table was always far-fetched. Washington and Kyiv both maintained that position as a negotiating tactic, but I have yet to talk to anyone in anything approaching an official position who believed that it was possible, either American or Ukrainian. It was eventually going to have to be dropped, and so the question is merely “was this a good time to drop it?” and honestly at this point I don’t know; if it jumpstarts negotiations and if those negotiations reach an acceptable conclusion then it was worth it.

NATO is something I feel a bit more strongly about. I think that the open letter from a group of foreign policy analysts arguing that NATO membership should be taken off the table was wrong to the point of intellectual irresponsibility, and I think that NATO could play a hugely important role in securing a better peace between Russia and Ukraine. It is evident, however, that the Trump administration and several NATO partners don’t feel that way, and consequently it’s a negotiating chip rather than a potential reality.

Regarding what looks to be the emerging structure of negotiations… however much Trump and Putin want to settle this alone, it is functionally impossible to exclude Ukraine and Europe from the negotiations, something that Rubio seems to understand. Any plausible outcome is going to place obligations on both Ukraine and Europe, and consequently they need to have some stake in the outcome. For me, the single most important outcomes are a security guarantee and a guarantee of Russian non-interference in Ukrainian democratic politics. From what I’ve been reading thus far thinking on the former seems to be outpacing thinking on the latter; evidently Russia is insisting on Ukrainian elections at some point during the process, elections that Russia hopes to control.

Shortly after Trump’s election Matt Duss and myself made the argument in Foreign Policy that Ukraine needs to be looking for a way out:

It is clear that Ukraine does not have a path to a straightforward victory. Ukraine’s incursion into Russia this past August seized hundreds of square miles of Russian territory—the first time any foreign army has done so since World War II. While this might have provided a morale boost to Ukrainians tired of only playing defense and a propaganda hit to Putin, it is unclear how it will translate into overall victory. It has shown that concerns United States and European allies have expressed about Russian red lines may be overblown, but it is not certain that the Trump administration will have an interest in relaxing those red lines in any case.

More broadly, the military situation appears quite desperate and increasingly serious for Ukraine. Russia’s ability to reconstitute its military power through mobilization, the rehabilitation of old military equipment (with China’s assistance), the borrowing of soldiers, and munitions from North Korea has enabled it to restore a degree of momentum to the battlefield.

Ukrainian forces are falling back on several fronts, even as they exact a high toll on the Russians. Ukrainian efforts at further mobilization have created political conflict and failed to address the imbalance between Russians and Ukrainians available at the front. Moreover, Russia’s precision drone and missile campaigns against Ukrainian electrical systems and other infrastructure have drawn an increasing toll from Ukraine’s civilian population.

And yet, grounds for negotiation remain. While there are some on both sides of the political spectrum in the United States who oppose the country’s support to Ukraine for various reasons, the public has remained largely supportive. Ukraine has unfortunately become a partisan political issue in Congress, yet recent polling shows strong pluralities in favor of the United States both supporting Ukraine “as long as it takes” and encouraging Ukraine to engage in conflict-ending diplomacy. It’s important to recognize that these two positions are not in tension.

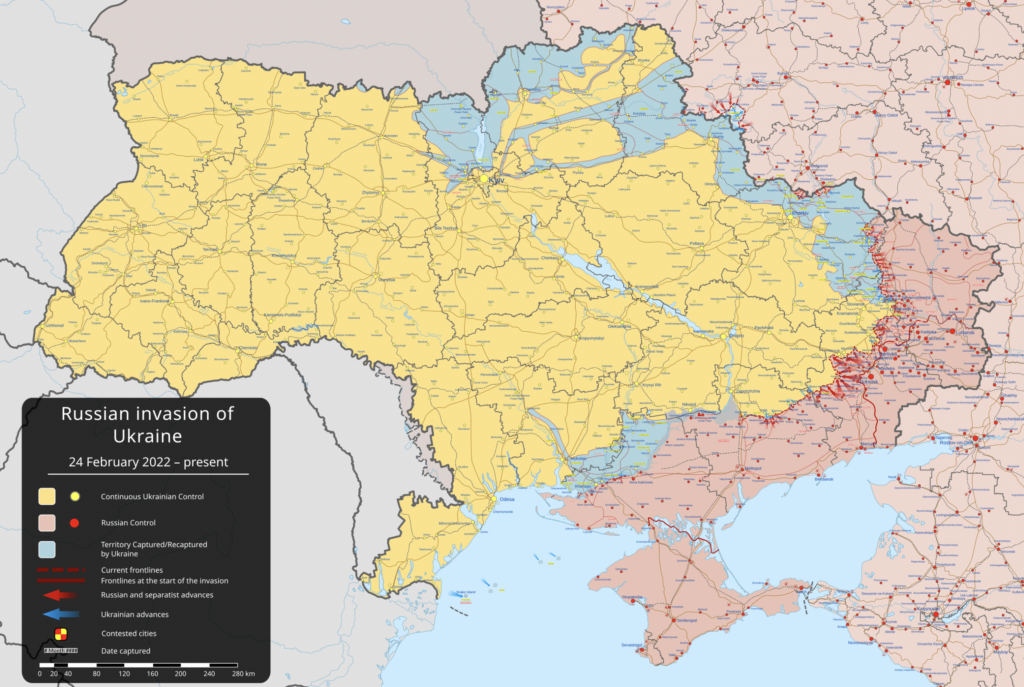

Back in 2022 and in early 2023 I argued against early overtures to Russia for a cease-fire deal, but it’s clear that the time has come to probe what Russia is willing to offer at the table. The answer to that question may be “nothing,” or possibly “nothing that can be achieved at reasonable cost,” but two factors have changed Ukraine’s prospects. The first is the difficult military situation; Russia is advancing in Kursk and in Donetsk, and the Ukrainians don’t seem to have a good solution to either of those problems other than hoping winter freezes the Russians in their tracks. The second is the new political situation in the United States, the full implications of which are not yet clear but clearly carry extraordinary danger for Ukraine.

Both Matt and I have been vocal defenders of support for Ukraine on social media, and the publication of this article has led to a predictable deluge of bad faith and not-quite-so-bad-faith demands for accountability regarding that support. Much of this comes from tankie and pro-Russian trolls and can be safely ignored. If you argued from February 2022 on that Ukraine needed to sacrifice its independence in return for peace, or if you argued at essentially every point in the first six months of the war that Ukraine needed to pursue an immediate ceasefire (prior to the recovery of Kharkiv, Kherson, and Snake Island), you don’t get any particular credit for making the same argument in fall 2022 (more on this in a bit). Making peace with Russia on terms acceptable to Russia has very high costs of its own.

The big question is what could have been done differently in fall 2022, when Ukraine was more aware of the robustness of the Russian defense around Kherson than its partners and when Ukraine was at a territorial high ebb. There’s certainly a “why didn’t you leave the poker table before you lost all those chips?” rejoinder to this argument, but I think a sound case can be made (and was made, by some) that Ukrainian military successes were going to be harder to replicate moving forward. Our own Leeward Mountain made that argument in comments.

I remain ambivalent about this. It’s not wrong exactly, but it would have been enormously difficult in political terms for the Zelenskyy government to reject an offensive and instead hunker down in a defensive pose. When I was in Ukraine in September 2023 optimism about the offensive was still running high (it had basically failed by this point), suggesting that the Ukrainian public was in no mood for a hunker-down strategy.

I also think that there were some unsettled questions about Russian military capacity in the fall of 2022. This is important, because too many folks will look at national-level metrics such as population and GDP and say “Russia big, Ukraine small, question answered” (you’d be surprised how often you get that kind of analysis, even from “Realists” who should know better). In fall 2022 it was not at all certain that Russia would be able to pull together its existing forces in a way that would allow it to defeat a concerted Ukrainian military assault, especially given that the Kharkiv offensive was haphazard at best. One does not need to delve too deeply into Russian military history to find major collapses, and it seemed possible that a well-trained, well-equipped Ukrainian force would be able to crack a Russian Army even if the latter was fighting out of prepared defenses. Similarly, it wasn’t obvious that Russia would be able to reconstitute military formations capable of making offensive progress in case the Ukrainian offensive failed to make much headway. This mattered insofar as it affected the level of risk that the Ukrainian offensive represented relative to a “hunker down” defensive strategy. Questions of Russian national cohesion were also unanswered in late 2022; they’re still unanswered today, except insofar as “more cohesive than we might have hoped.”

And of course all of this is so much window-dressing if Putin was uninterested in a diplomatic settlement in fall 2022, and I’ve yet to see any very concrete account that he was; foregoing offensive operations in the hope of a diplomatic settlement that then results in breathing space for the reconstitution of military power represents its own set of risks. If Zelenskyy had (through spending immense political capital) foregone the summer 2023 offensive in the hopes of creating the grounds for a ceasefire, we might very well all be kicking ourselves if Russia rejected the overture and resumed its own offensive anyway.

But here we are. The Russian Army did not collapse. Russian popular support for the war did not collapse. The Russian Army has been able to reconstitute offensive military power and is placing enormous pressure upon Ukraine. Despite its real technological advantages at the front, Ukraine has not been able to fully mobilize its population for war. Ukrainians grew frustrated with Biden and have grown frustrated with the war. Trump has been elected, and his buddy Elon is now contributing on questions of foreign policy. Saying that “we lost because of Trump,” is neither here nor there because Trump’s election was always a possibility, and not one that was overly dependent on the current state of the war. No matter how likely or unlikely all of these die rolls were, they now represent the reality that we have to deal with.

The thing about Trump is that we still do not know what Trump intends to do with Ukraine. Peace negotiations take a long time, even to try to reach a cease-fire, and Moscow and Kyiv and their supporters have not really even started the work that will need to be done. Just as Joe Biden could not simply order either Israel or Hamas to stop fighting, Trump cannot order Ukraine to lay down its arms and accept Russian terms. Trump is sensitive to criticism (especially with regard to Russia) and knows how the fall of Kabul made a permanent dent in Biden’s popularity. He doesn’t want Kyiv to fall on his watch.

There’s the very real possibility that Russia will reject any set of terms that Ukraine finds acceptable… but Russia is in very serious trouble itself. Its counteroffensive in Kursk and its offensive in Donetsk have both stalled after suffering extraordinary material and personnel losses. It’s economy is suffering serious damage, albeit not serious enough to collapse either the war effort or the government. But Ukraine needs to rebuild, and it needs Europe’s help to rebuild. Without a US commitment of support Kyiv cannot continue fighting indefinitely.

Photo credit: By Viewsridge – Own work based on: Russo-Ukrainian conflict (2014-2022).svg by Rr016 & Ukraine adm location map improved.svg by Yakiv GluckTerritorial control sources:Template:Russo-Ukrainian War detailed map / Template:Russo-Ukrainian War detailed relief mapISW, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=115506141