This Day in Labor History: January 14, 1977

On January 14, 1977, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union lost a union election in Los Angeles after the Immigration and Naturalization Service raided the workplace, deporting many of the union activists. This disgusting action helped spur the ILG to move toward working with immigrant rights groups to build the larger alliances between the labor and immigrant rights movement that exist today.

The American labor movement’s relationship with immigration was pretty terrible for most of its history. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first major law in American history that originated with the American labor movement. American Federation of Labor head Samuel Gompers notoriously co-wrote “Meat vs. Rice,” the 1902 pamphlet about how American workers couldn’t compete with Asian workers who only needed to rice to live. Eastern European immigrants weren’t treated much better, whether the Knights of Labor’s opposition to “Hungarians,” or labor’s support for the 1924 Immigration Act, which effectively stopped two generations of intense immigration from eastern and southern Europe. In terms of migration from Latin America, the movement’s history was slightly more complicated, in part because that did not become a major issue in American immigration history until a bit later. But labor certainly did not oppose the 1930s deportations of Mexican and Mexican-American workers and as late as United Farm Workers head Cesar Chavez demanding the deportation of undocumented workers competing with his workers (without asking his workers what they thought; in fact, a lot of these workers were their own family members), fear of immigrants outcompeting “American” workers remained powerful.

But by the 1950s, the reality of farm labor in southern California required a somewhat more nuanced approach to migration from Latin America, which meant the formation of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee and opposition to the exploitative Bracero Program, but not necessarily immigration from Mexico itself. As Mexican and then Central American workers became a bigger part of the workforce in California, the labor movement simply had to take them more seriously. Larger swaths of the labor movement began to move away from its traditional anti-immigration stances and more to the point, these were the organizing unions.

Many of these more progressive unions were growing. One that was very much not growing was the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. The ILG was long way from the era up the Uprising of the 20,000, with young Jewish socialist women taking to the streets of New York to fight for their rights under leaders such as Clara Lemlich and Rose Schneidermann. Capital mobility had decimated the ILG and other garment worker unions. But the ILG had a footprint in Los Angeles going back to the 30s and 40s, when shops opened there with largely Mexican workers and which had a major strike there in 1933.

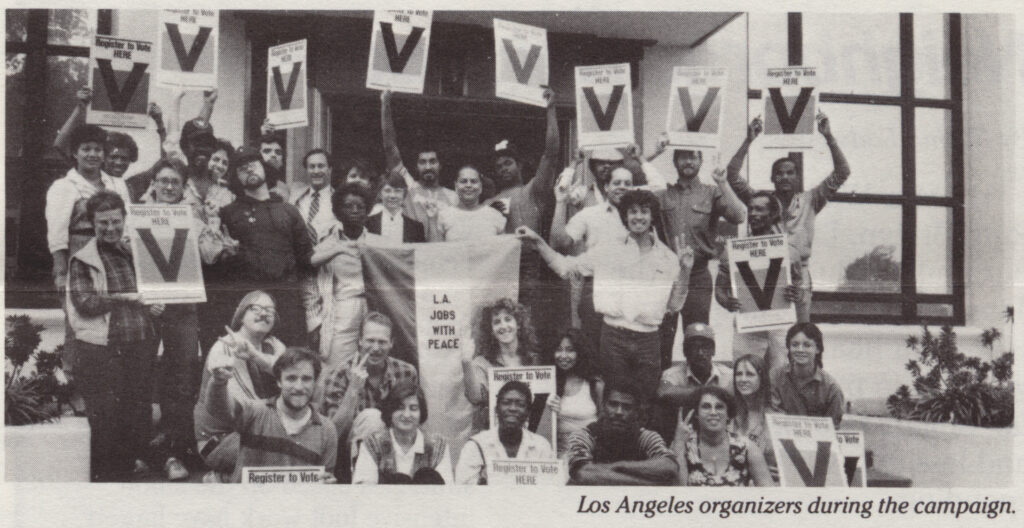

Los Angeles was changing rapidly in the 1970s. Once the most anti-union city in America and one that deeply imbibed conservatism, the rise of mass Mexican migration and the 60s generally challenged the city’s leadership. It began sprinting to the left politically, with all sorts of social activism roiling this one staid city. A lot of this was Chicano activism and a lot of the workers laboring in the LA garment factories had at least some interest in this. The ILG began hiring Spanish organizers and taking LA more seriously, building up highly politicized organizing capacity.

Now, the garment manufacturers–who still run basically the same model from the Triangle Fire to the Rana Plaza collapse–had a good method for undermining unions in their shops. They would call the INS to deport their own workers. Oh whoops, we had no idea that we hired undocumented immigrants, better round them up! But although these were undocumented immigrants, a lot of them were quite willing to join unions and engage in labor activism, despite the risk. Unions hired more Spanish speaking organizers and brought in more community activists without traditional ties to labor to connect with the communities they were organizing. They also took on a more aggressive pro-immigrant stance that wanted to get the migra out of the workplace entirely. A lot of these workers were also political refugees and brought radical politics from Mexico and El Salvador and other nations to the workplace. ILG also hired some of the fired radical workers as organizers.

Now, the ILG had a much harder time signing up Asian workers than Latino workers and this divided the workplace. It also gave employers power. So in January 1977, two companies fired workers just before a scheduled union election. Eliminating the militants put the election in the hands of the anti-union Asian workers. Ten days before the election, on January 4, the Lilli Diamond textile plant had the INS come and get rid of their workers. And ten days later, the ILG lost the election among the remaining workers.

But the ILG did not accept this defeat lying down. Although by the late 70s, the NLRB was already a sclerotic agency that did not move quickly enough to actually help workers, the union first tried for redress through its processes. It didn’t do much. So the LA local of the ILG got the international to file a lawsuit over the targeting of union supporters. ILG international leadership was pretty ambivalent about immigration still—ILG International leadership had long had a reputation for being out of touch with their rank and file workers. But the agreed. Working with immigrant rights activists, the union moved around the NLRB and into the courts where immigration policy could be litigated. Courts began to agree and reversed deportation orders at various plants. The union began to win contract language about immigration agents, including informing the union when INS agents were in the factory.

Although by the early 80s, the ILG had withdrawn its support for the Los Angeles campaign, noting the millions spent for maybe 1,000 new members, the courts continued to give the local and its immigrant rights allies wins. Until William Rehnquist that is. The old racist in INS v. Delgado decided for the majority that workers did not feel constrained by the presence of INS agents inside a plant. William Brennan wrote the dissent, but of course dissents are generally meaningless and that was that.

Still, the ILG local in LA continued working on immigrant rights issues through the 80s, sometimes winning campaigns, sometimes resisting employer attempts to roll back gains in already unionized plants. Obviously, these campaigns did not turn around the labor movement. But they did contribute materially to new alliances between the labor movement and immigrant rights movements that continue to be strong today.

I borrowed from Tobias Higbie and Gaspar Rivera-Salgado, “The Border at Work: Undocumented Workers, the ILGWU in Los Angeles, and the Limits of Labor Citizenship” published in Labor in December 2022 to write this post.

This is the 545th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.