Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,807

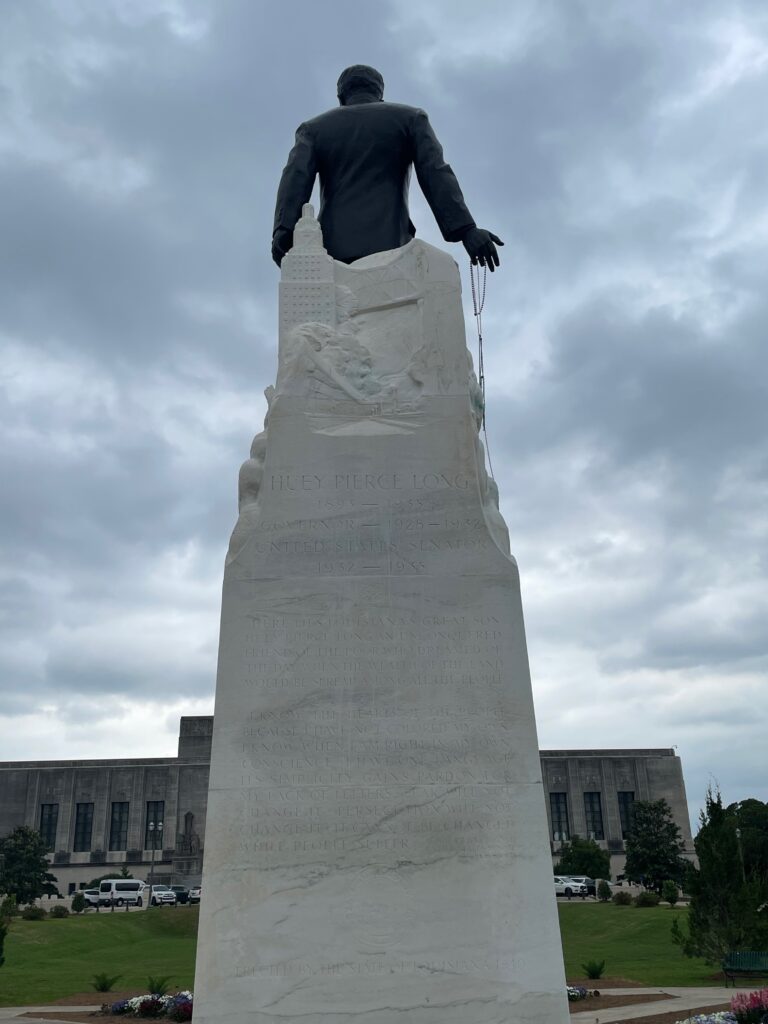

This is the subtle and understated grave of Huey Long.

Born in 1893 in Winnfield, Louisiana, Long grew up poor. He supported himself as a traveling salesman. But he was super ambitious, though not initially for politics. He went to whatever college he could to get that education he so wanted–three in the end. He decided on the law as a profession and passed the bar. By this time, he started to have some political ambitions and he was good at hating the rich. That was his thing–he represented the poor against the corrupt elite of Louisiana who he knew would never accept him or people like him. This was the thing in the post-Populist era. The Populists had real play in much of the South because everyday white folks were so bitter about being led by corrupt people who didn’t care about them. When racebaiting didn’t work to get the poor in control, the rich just went around fixing elections. That kept them in power and it fed hopelessness among the poor whites but it didn’t paper over any of those resentments. Long became really good at tapping into that and took cases that would represent the poor against the corrupt interests.

It didn’t take Long to see the path before him. He ran for the Louisiana Public Service Commission and won on a populist platform that he soon turned to suing the companies ravishing Louisiana, such as Standard Oil. In fact, attacking the oil industry was core to his political identity. It wasn’t oil development that he and his supporters hated, it was who benefitted from it, which was definitely not them. He was a great lawyer–really, William Howard Taft, then Chief Justice, called him “the most brilliant lawyer who ever practiced before the United States Supreme Court.” And say what you will about Taft–he knew his lawyers.

Long wanted power. He ran for governor in 1924, but lost. When he ran again in 1928, it was as a full bore populist, attacking the powers that ran the state. He won and he sought to put in his program that centered around him and how he could deliver for the state of Louisiana. A lot of these programs were really good–expanded social programs, big public works projects, good roads. He also made Louisiana’s state capitol building the tallest in the nation, which whatever. In 1931, he proposed a cotton holiday, where farmers would simply refuse to grow cotton until the prices rose to an amount where a farmer could make a living growing it. So no one would grow it in 1932 and that would show those big industrialists who controlled the economy.

It’s impossible to overstate how much Long’s opponents hated him. The hate was two-pronged. First, the mainstream Louisiana Democratic Party was filled with right wingers who wanted to do nothing for the poor ever, no matter the race. So the fact that he was investing in programs to help people was complete anathema. The other reason for the hate was of course personal–he was a demagogue threatening to rule the state by fiat and that disgusted these people both personally and on principle. The legislature impeached Long in 1929 for abuse of power, but he used his behind the scenes magic plus the fury of the people to defeat that effort. Long seemed unstoppable.

Then in 1930, Long decided he wanted more revenge against the old-line Democrats. Joseph Ransdell was running for reelection to the Senate. Long wanted nothing more than to crush him. So he did. He ran for the Senate and won the primary with 57 percent of the vote. Long still had a governor term to finish up, so he didn’t bother showing up to Washington until 1932.

Long was an early supporter of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932. He brought his anti-corporate barnstorming to Washington at a time when there was a lot of space for that. He was most certainly the kind of populist who thought in conspiracies–his case was that Standard Oil and other such companies controlled the world economy and that the U.S. should stay out of anything reeking of foreign influence. There’s almost no question that Long would have been an extreme isolationist in the late 30s and early 40s.

It didn’t take Long any time at all to start opposing FDR though. A lot of this was personal. Long was not a man built to be subservient to anyone. He needed the limelight. So he started criticizing the New Deal as too timid, which was a fair critique of the early legislation, and presenting his own program intended to raise his own profile that could only be satisfied by sitting in the Oval Office himself. In February 1934, he announced his Share Our Wealth program. The ideas were mostly pretty good and in fact many would become central to the Second New Deal after FDR’s 1936 reelection. At the core was a heavy tax on millionaires. It was simple. Personal fortunes over $1 million would be taxed at 1%, over $2 million at 2%, until you got to $100 million, which would be 100% taxation. He had another proposal to limit annual income to $1 million, with 100% taxation after that. His third prong was to cap individual inheritances at $5 million. Now, I’d be fine adopting this very law as it is for the present–no one needs that kind of money–but it’s important to remember that $100 million then is $2.3 billion today so his tax really was on the extreme rich. What would all this fund? Free higher education for all. A 30 hour work week with 4 weeks of paid vacation. Old age pensions. Farm relief. Public works projects. Higher pensions to World War I veterans. A universal health system.

I mean, this sounds pretty good! But of course Long was a deeply problematic figure. Whether he was a fascist or not is not a debate I find fruitful, but he was most certainly a demagogue. He toured the nation promoting his proposals and Roosevelt was really worried about a third party challenge in 1936. Long was basically still controlling Louisiana with him telling the governor what to do and there was talk about violent insurrection from some of the opponents of his machine. Like, when Long visited Baton Rouge, he still used the governor’s office as his personal office. To say the least, Long was on the personal take through all of this and corruption was rampant.

In 1935, Long was visiting Baton Rouge to push a bill that would gerrymander an old enemy of his out of his judgeship district. After it happened, the judge’s son in law walked up to Long and shot him. Long was surrounded by bodyguards and they fired at least 60 bullets into the guy’s body. But Long died two days later.

Long was 42 years old upon his death.

I have written 1100 words on Long and have barely even touched on many important issues. We can leave that for comments. Save Our Wealth fell apart shortly after his death. But his political machine continued dominating Louisiana for a long time, with his son Russell a long time senator who chose to use his gravestone as an essay. Also, I finally read Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men last year and thought it was a great novel. The book of course is a lightly fictionalized version of Long’s life.

Huey Long is buried outside the Louisiana State Capitol, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Typical understatement.

If you would like this series to visit other controversial figures from the 1930s, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Francis Townsend is in Compton, California and Charles Coughlin is in Southfield, Michigan. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.