Gaming Notes

My Steam Replay dropped last week, which was a reminder that I should put together another one of these posts before the year ends. I don’t use Spotify, so the annual hoopla over Spotify Wrapped tends to pass me by, but Steam Replay usually offers some surprising revelations. To wit: for someone who doesn’t think of herself as an avid gamer (and who can—and this year, has—gone months without playing anything), I actually play a lot of games. I’m even well above the Steam median in games played and achievements unlocked.

There’s an obvious solution to this mystery: the kind of big, open-world games that you can easily lose hundreds of hours to, like the latest Baldur’s Gate or Star Wars extravaganza, hold almost no appeal to me. I tend to play smaller, shorter games. And when a game catches my interest, I tend to play it obsessively, trying for every possible achievement. Hence, more games played, and more achievements racked. But still, I don’t feel like gaming has been a major element in my leisure time activity this year. This final batch of games feels more like a grab-bag than something a dedicated gamer would play.

Before I get to the reviews, a few interesting bits of gaming news. Two games I’ve previously discussed have released major patches. Slay the Princess has come out with The Pristine Cut, which adds new storylines and a new ending to an already furiously branching narrative tree. I haven’t played it yet—frankly, exploring the myriad story options in the original game was already a little bewildering, and I’m not sure I have the energy to seek out the parts of it that are new. But if you were intrigued by my thoughts on the game, the version currently available is the one that developers Black Tabby Games consider the definitive one. Second, Potion Craft: Alchemist Simulator has released a major quality of life upgrade which makes significant gameplay adjustments, allowing the player to control the ingredients grown in their garden, and massively overhauling the game’s skill tree. Since quality of life issues were my main complaint about Potion Craft when I wrote about it last year, I was eager to see the effect of these changes, and I have to say that my gameplay experience was massively improved. Consider my previous mixed review upgraded.

Finally, Swedish developers Something We Made have announced a sequel to their charming photography-and-exploration game Toem. The game’s conceit was simple and compelling enough that I can easily imagine a sequel being just as enjoyable as the first installment. The current projected release date is some time in 2026, but I’ve already got Toem 2 on my wishlist.

As usual, consider this post an invitation to talk about your own gaming. What is the best game you played in 2024? What are you looking forward to in 2025? Are you planning to do any gaming over the holiday?

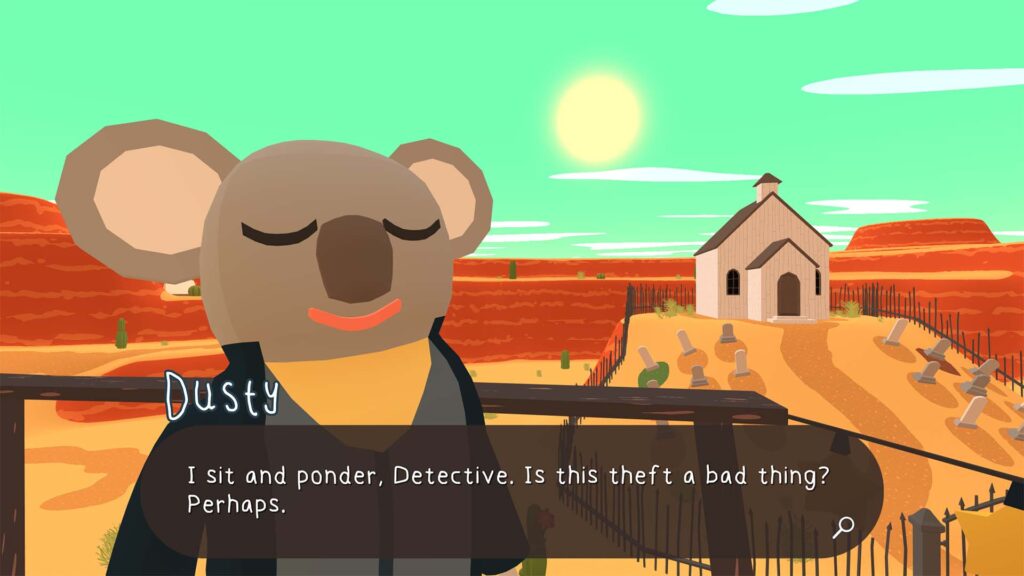

Frog Detective 1: The Haunted Island (2018)

Frog Detective 2: The Case of the Invisible Wizard (2019)

Frog Detective 3: Corruption in Cowboy County (2022)

A lot of the games I talk about in these write-ups are detective games, for the simple reason that they combine two things I enjoy in gaming: puzzles and a strong story. So right off the bat I have to clarify that Australian studio Worm Club’s Frog Detective trilogy doesn’t exactly tick either of those boxes. You play the titular detective, who in each game is dispatched to unravel a different mystery: what is causing the strange nighttime noises on a remote island? who destroyed the planned welcome party for a new resident in an exclusive neighborhood? who stole all the hats in an Old West town? The means of solving these cases, however, are more in the vein of scavenger hunts. You have to collect a certain number of cactus flowers to go in a stew to give to a town resident to get a painting to give to another resident, and so on and so forth. (Puzzle-wise, the Frog Detective games can easily be played by children, though they have a knowingly childish tone that might best be appreciated by adults.) The solutions to the mysteries, too, are simple to the point of absurdity, often hinging on misunderstandings or verging on surrealism. The source of the nighttime noises on the haunted island, for example, is a chicken who is preparing for a dance contest, who has decided to hold her practice sessions in a convenient cave.

This profound silliness is where the Frog Detective games’ true appeal lies. Everyone in these games is monomaniacal and over-literal—when Frog Detective is given a notebook to hold his case notes at the beginning of the second game, the giver won’t let him leave before he decorates it with stickers—while also being pretty phlegmatic about matters of ego and self-regard. Frog Detective—who never goes anywhere without his trusty magnifying glass—cheerfully admits that he is only the second-best detective in his department, repeatedly reminding his supervisor (whose name is “Supervisor”) that he is being sent on assignments because the top guy, Lobster Cop, is busy with more important cases. On the other hand, when suspicion falls on Frog Detective for the hat heist, everyone agrees that he’s the most likely suspect, because the shape of his head must make him an inveterate hat-hater. Even the game’s graphics, which consist of large, uneven blobs of color that look like they were cut out of construction paper by a preschooler, seem in on the joke.

It’s the sort of humor that can wear thin rather quickly, but happily each of the Frog Detective games lasts only an hour or two, and along the way they manage to get in a few pointed jabs at the whole copaganda industry—when the theft of hats turns out to be an actual crime rather than, as in the two previous games, a misunderstanding, everyone is shocked to discover that “crime is real?!” If nothing else, the Frog Detective games, in all their deliberate ugliness and no-less deliberate absurdity, are clearly a labor of love made by people who are determined to be weird, and though they wouldn’t be my first recommendation as a gaming experience, I have to appreciate them for that. (All three Frog Detective games have been released jointly under the title Frog Detective: The Entire Mystery.)

Firmament (2023)

In my last games roundup I waxed rhapsodic about Cyan’s remaster—which was really a total reimagining—of their best game Riven. This reminded me that there is a Cyan game I still haven’t played, which is why I must now deliver the whiplash-inducing judgment that Firmament is one of Cyan’s worst offerings. The game starts in a familiar enough fashion. You wake up, a nameless, personality-less first person player character, in a strange, involved location full of levers to pull, pathways to clear, and mechanisms to activate, and have to work out what has happened here, and what you can do about it. Two things set Firmament apart from this established template. First, the player is accompanied by recordings of a nameless woman, who explains that you are a Keeper in charge of caring for the Realms, and that in the wake of some unspecified emergency you must make them ready for the Embrace. (There are a lot of Capitalized Nouns in Firmament.) Second, you are immediately furnished with an Adjunct (see?), a kind of multitool that fits over your arm, with which you can activate various terminals that control doors, bridges, carts, engines, and many other machines scattered throughout the game’s worlds. As you wander through the suspiciously empty Realms, your guide’s narrative reveals a history of abuse, exploitation, and betrayal.

The problem with this is that it’s all terribly boring. For one thing, visually. Firmament has gorgeous graphical capabilities, but the vistas and settings they’re used to reveal are all samey and nondescript. A glorious, snowy mountain range looks stunning the first time you move through it, marveling at the detail on every rock and snow bank. After a few minutes, when you realize that generic natural scenery is all you’re going to get, it starts to feel a bit dispiriting. The same is true of the structures you encounter, such as the Spire (there we go again) whose beauty your guide marvels over, but which in actuality is just a mass of different shapes thrown together. Cyan games are known for the level of thought that goes into their settings—the architectural and decorative flourishes on every structure, the scattered artifacts that suggest how these spaces were used by the people who lived in them. All of that is absent in Firmament, as is a sense of those people—Cyan players will be accustomed to a wealth of documentary evidence and environmental storytelling, but in this game these are very thin on the ground. The result is that the thrill of discovery that accompanies most Cyan games, the emotional involvement one develops with their settings and characters, are almost entirely absent. (After Firmament was released, Cyan came under fire for using AI to generate in-game texts and documents, but if this is what you get from those tools, I’d say Firmament is a great advertisement for the irreplaceability of human artists.)

That same tedium afflicts Firmament‘s puzzles, which mostly involve figuring out industrial processes: activating a steam engine, or supplying precursor materials for a chemical factory. There are some neat moments along the way—the player gets to ride a block of ice down a chute, or don a protection suit and venture into a vat of sulfuric acid to hammer away at encrustations that are keeping its mechanism from working. But not a single puzzle in Firmament felt fun, or gave me a sense of accomplishment when I solved it (in fact, after a certain point I was so enervated that I started reaching for clues just to keep things going). The magic of Cyan games is how they get you involved in their worlds, immersing you in their logic until the solutions to their puzzles are more a matter of understanding how the world works than figuring out specific clues. In Firmament, all that weight of meaning is held off until the game’s final revelation—which, in fairness, is a solid one, and even takes advantage of the players’ assumptions about Cyan games to pull the rug out from under us in certain ways. By the time I got to this point, however, I was more than ready for Firmament to be over.

Paper Trail (2024)

When you boil them down to their essentials, there are only a few different kinds of puzzle games. Path-finding games, in which the player has to get a character from one side of a game board to another, according to an increasingly complicated set of rules and limitations, are an extremely common type, and it takes a bit of ingenuity to come up with a novel twist on the concept. British developers Newfangled Games have lit on one such twist in their latest game, in which they treat the game board as a piece of paper, which the player can fold in over itself, revealing different elements on the reverse side that can change the board’s configuration and create new paths across it. You control Paige Turner (geddit?), a high school graduate making her way from home to university, a journey that traverses caves, swamps, oceans, cities, and many other locales. The basic rules are quickly established—you can’t fold over a fold, or over Paige herself—but like any good puzzle game, Paper Trail quickly adds more and more complications to its premise—switches that open doors or raise bridges, oddly-shaped game boards, or ones where folding one piece of the board will cause another part of it to fold as well.

The puzzles are tough but fair, and like the best sort of brain teaser, they work mainly because they force you to adjust your mode of thought, to treat a game board not as a fixed entity but as something that you can manipulate. An in-game hint system is similarly effective, showing you the folds required to solve each level but leaving out other actions—where you should move Paige and other manipulatable objects—so as to maintain a level of challenge. I’ve spoken in the past about how the right toughness level for a puzzle game is an incredibly personal thing, but for my money, Paper Trail sits right at the sweet spot. If there’s a criticism to be made of the game, it’s that its story, the reason Paige is running off to university, is a rather banal one. That’s hardly a deal-breaker in a puzzle game, of course, but especially in the type of puzzle that is about getting a character from one point to another, it helps to cement your emotional involvement if there’s a good story about why they’re doing that. The one in Paper Trail, which involves disapproving parents and a lost sibling, is trite enough that I came to resent the time the game spent on it. In the end, however, this is a minor aspect of the game, and the thrill of accomplishment that comes from getting Paige to her destination more than outweighs her unoriginal reasons for going there.

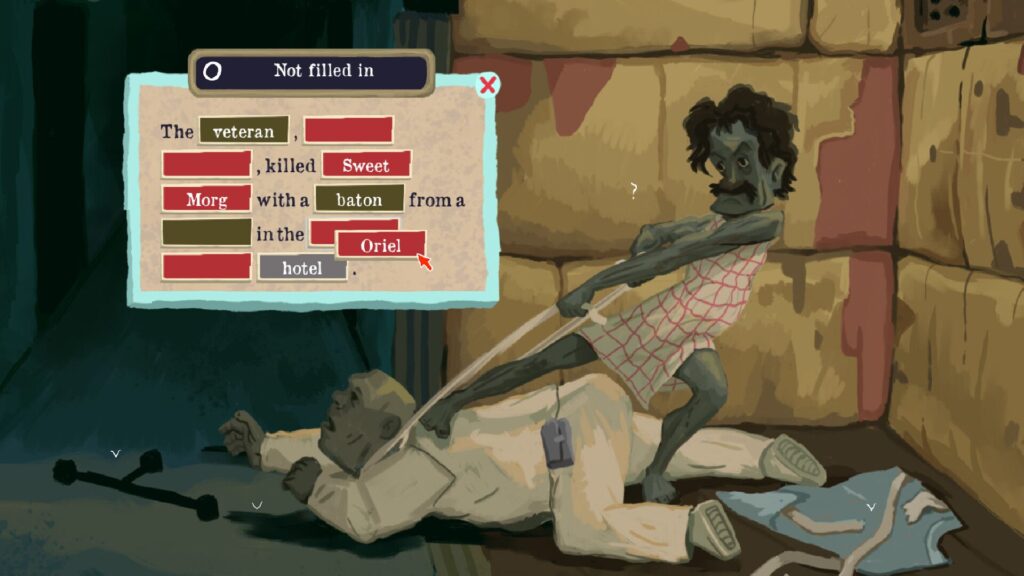

The Rise of the Golden Idol (2024)

There are two 2024 games that I bought on the day of their release. One is the Riven remake, and the other is Color Gray Games’s sequel to their delightful, addictive 2022 mystery game The Case of the Golden Idol. Both have ended up as my favorite games of the year. Which is a sign that I know that I like, but also that these games’ developers have done a good job of holding on to to what works, and making it even better. Like its predecessor, Rise of the Golden Idol presents us with a series of vignettes, mostly having to do with murder or other kinds of violence—a woman tearfully rakes over the dirt in her garden, while her house bears unmistakable signs of a recent affray; a crowd flees a drive-in theater after one of the cars bursts into flames; an auction is thrown into disarray by sudden darkness, while in the next room, a security guard is electrocuted. In each scenario, the player must investigate—rummage through people’s pockets, leaf through calendars and post-it notes, and combine all that with information from previous chapters—in order to fill in puzzle pages identifying who is who, what has happened, and who is at fault. It’s a pure logic puzzle, given sizzle and pizzazz by an irresistible pulp adventure story. The first Golden Idol game was a historical mystery, in which clueless European explorers high on their own sense of superiority got more than they bargained for when they tried to exploit the powers of the titular artifact. Rise of the Golden Idol takes a classic, and utterly irresistible, sequel approach, in which modern people seek to apply science to ancient mysteries, only for it all to blow up in their faces.

Color Gray released two DLCs to The Case of the Golden Idol last year, which expanded its story and delivered more puzzly goodness. But as much as I enjoyed going back to the world of this game, I found those mysteries frustrating, with too much information flooding the zone, and too-convoluted questions requiring me to perfectly lock into the developers’ state of mind (once again, this sort of thing is extremely personal, but I’ve heard similar reactions from people who are much better at puzzles than I am). Rise of the Golden Idol is a much smoother experience. The puzzles are tougher than in the first game, often requiring the player to piece together information from different time periods, and to keep track of the trajectories of a wide array of characters. But unlike in the DLCs, this isn’t toughness for toughness’s sake. The game plays fair, and if you pay attention, the solutions will often present themselves. The range of puzzles is also much wider—you have to figure out which neighbor lives in which unit in an apartment building, or identify different exotic birds at a sanctuary, or (in one of my very favorite puzzles) interpret a message conveyed through the medium of dance—which makes the whole thing so much more fun. A big help is that Rise makes some substantial improvements to the original game’s interface, which streamline the puzzle-solving process, allowing you to focus on one question at a time. (Some of these changes have also been incorporated into The Case of the Golden Idol, which released a massive, free quality of life upgrade shortly before Rise‘s publication.)

None of this, of course, would matter if Rise of the Golden Idol didn’t have a great story, and here too the game outdoes its predecessor, following multiple characters across different strands of story, each seeing their own bit of the elephant while the player grows more and more alarmed at what’s happening. As the oblivious scientists (and eventually, executives) at the story’s center use their discovery for ever-more immoral ends, the ripple effects of their actions spread outward in unexpected ways, claiming unsuspecting victims, and building up to a terrifying grand finale. It isn’t one of the game’s official puzzles, but putting together the game’s timeline and realizing how its characters affect each other in unexpected ways is yet another way in which Rise of the Golden Idol is a compelling, satisfying mystery, a more than worthy sequel to an already great game.