Finding Slave History

This is good news for those of us who care about a truthful discussion of the historical record:

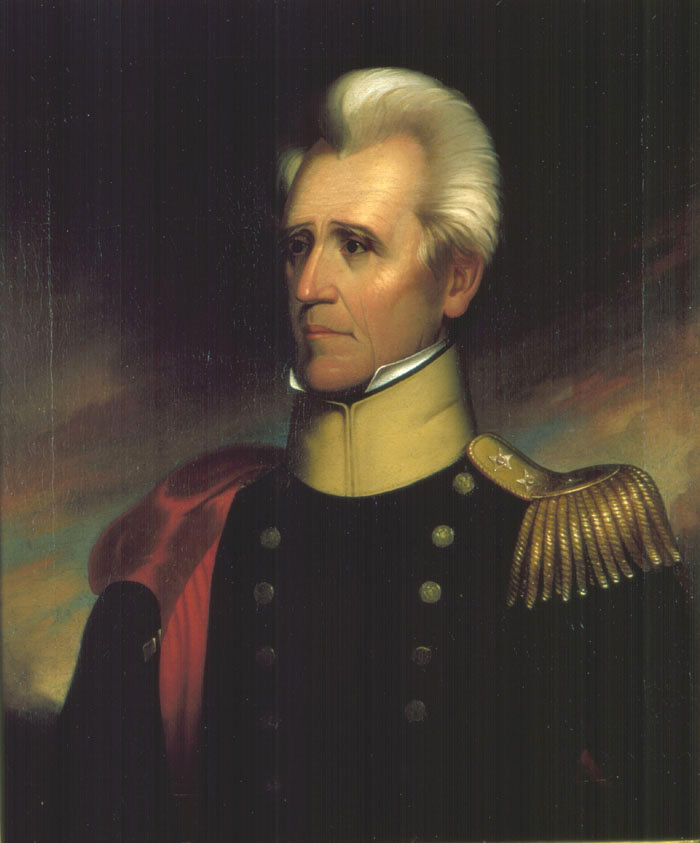

At least 26 enslaved people died on the Tennessee plantation of President Andrew Jackson between 1804 and the end of the Civil War in 1865. Where they were laid to rest is knowledge that had been lost to time.

But on Wednesday, the Andrew Jackson Foundation announced a discovery: They believe they have found the slave cemetery at The Hermitage, the home of America’s seventh president.

An old agricultural report from the 1930s had given them an idea: It mentioned an area that was not cultivated because it contained tall trees and graves. They also suspected the cemetery would be near the center of the 1000-acre (405-hectare) plantation, and on land of low agricultural value. Late last year, with the help of an anonymous donor who was interested in the project, they cleared trees and brought in archaeologist James Greene.

Physically walking the property to search for depressions and gravestones yielded a possible site. Ground-penetrating radar and a careful partial excavation that did not disturb any remains confirmed it: At least 28 people, likely more, were buried near a creek, about 1000 feet (305 meters) northwest of the mansion.

Finding the cemetery after all this time was exciting but also solemn for Tony Guzzi, chief of preservation and site operations.

“For me, this is going to be a reflective space. A contemplative space,” he said.

Jackson was one of a dozen early U.S. presidents who owned slaves, and identifying their graves has been a priority at other presidential sites as well as historians seek to tell a more inclusive story about the people — enslaved and free — who built the young nation.

Richard Blackett, Andrew Jackson professor of history emeritus at Vanderbilt University, said that when he first came to Nashville 22 years ago, the film shown to visitors at The Hermitage did not even mention the enslaved people who had lived there.

“More recently, people have developed a keen interest in trying to understand the nature of enslavement, and the people who experienced it, and the people who imposed it,” he said. “And that has created a need to find out more about the people who were at the bottom of the totem pole, but the people who did all the work.”

But some other historic homes have done more, more quickly. Even two decades ago, it was known that there was a burial site at The Hermitage, along with the general location, he said.

My own experience at the Hermitage was pretty disappointing compared to that of Monticello or Montpelier, where the slave experience is much more centered. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t workers there doing what they can to make it better. Telling the stories of the Black workers who made Andrew Jackson’s life of luxury possible will only make for a more complete story of the American experience.