Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,776

This is the unmarked grave of Archibald Motley.

Born in 1891 in New Orleans, Motley grew up in the Black middle class. His mother taught school until she married and her father was a sleeping car porter, that entry into the middle class, even if it was a service job. Motley had to work as a kid though, in part because of his father’s health, which at one point required a six month hospitalization. He also learned about slavery from his grandmother, who lived with them and who had experienced it herself. In fact, she had been illegally taken from Africa long after the end of the legal slave trade and so told her grandson stories of Africa that really stuck with him. He was super into art and his parents encouraged him in it. He had gone to mostly white schools and then onto the Art Institute of Chicago. He was already into modernism and realism and did not fit in well with that school’s traditional ideology. He graduated from the Art Institute in 1918, but did not show his more experimental work for years, having learned not to expose himself to the conservatives, which affected him for years.

By the time he was in twenties, Motley was able to ride with his father on the railroad cars. I assume he was training to be a porter as well. This was during World War I. He got to visit all sorts of places he never could have gone before, from San Francisco to Atlanta to Philadelphia. He talked to people and learned about their stories and really experienced the horrors of southern segregation and violence for the first time. Like a lot of northern bred Black Americans, the shock he experienced on being treated like that and called names and all the other horrors of the more direct racism of the South changed Motley’s life.

The 1920s saw a lot of success for Motley’s work. The Harlem Renaissance is a problematic term in the sense that not all Black artists engaging in its trends lived in Harlem. That included Motley, as important as Langston Hughes or Zora Neale Hurston or Alain Locke, but based in Chicago. That’s why it is probably better called the New Negro Movement, as it was often referred to at the time. Locke’s idea of the New Negro deeply influenced Motley, with its emphasis on race pride and aesthetics, based around the representation of Black life and culture with great pride, whether highly politicized or (as in the case of Locke himself) not really political work. Much of this had to do with identity and its complexities in American life, which made a lot of sense for Motley, who as a light-skinned Black man, had to comprehend what that meant for him in the duality of the American racial system.

Like a lot of other New Negro artists, Motley was committed to ideas of racial uplift through art, something he came to believe was necessary while living through the 1919 race riots in Chicago. He painted a lot of portraits of the Black middle class and this brought him a good bit of success. His painting Mending Socks won a contest for the most popular painting showed at the Newark Museum in 1927. He was the first Black artist to have a one-man art show in New York City in 1928. That same year, he won the William E. Harmon Foundation Award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes, founded in 1926 and dedicated to honoring Black Americans in different fields. It often went to artists of various types in its early years, not just Motley but Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Claude McKay.

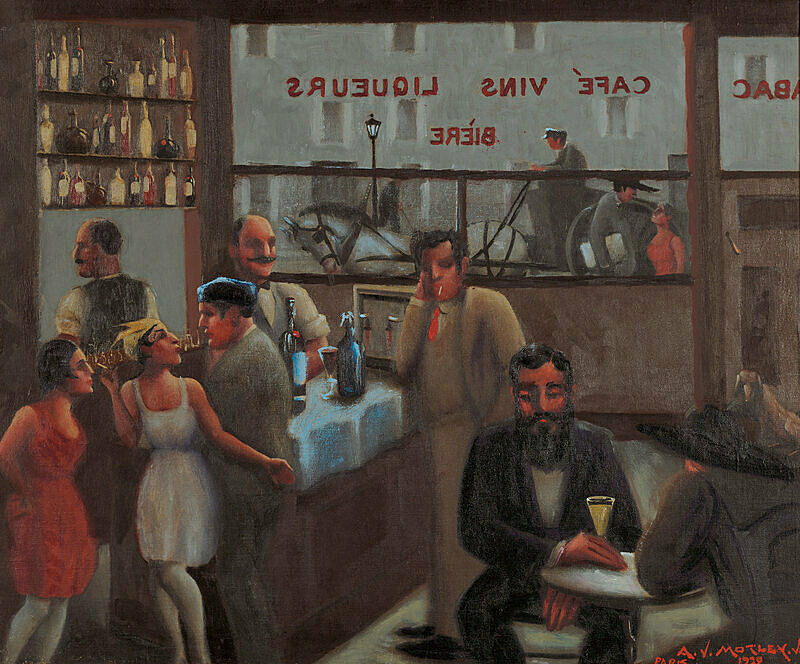

Motley became the most recognized painter of everyday Black life in the Jazz Age. His focus was not Harlem, but Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, as the Great Migration transformed that city and those people who all of a sudden were far from Mississippi by distance and increasingly by culture. Motleys’ astounding use of color allowed him to capture this amazing moment in time. He also worked hard to represent the Black community for all its colors, channeling his own thoughts about Black identity into community from which he came. Part of this was also didactic–he wanted to educate both Black and white communities about skin tone and identity. He completely rejected the long history of stereotype of portrayals of the Black community and wanted to represent everyone in his art. Some of his favorite sites to paint were the clubs and cabarets of the 1920s where people partied. His portraits were of people throughout the Black community, from very dark to his famous The Octoroon, reminded viewers of how Americans defined race.

Oh, speaking of his throwing up racial conventions, in 1924, Motley married a German woman named Edith Grazno. Her family disowned her for it.

In the 30s, Motley became a painter for the Works Progress Administration and did some great murals of Black life, which was rare in the great muralist era. But things generally slowed down for him after the mid-30s or so. His financial position wasn’t great and his artistic drive seems to have slowed. In 1948, his wife died and his finances got bad enough that he had to take a job painting shower curtains for a fancy brand of them. In the 50s, though, he started visiting Mexico and this created something of a revival in his work, as it has done for many American artists. Still, he would never again be the powerful force in the art world that he was in the 20s. That’s OK though, his impact was so huge in that era and not everyone has to be an amazing artist for decades upon decades.

Motley died in 1981. He was 89 years old. He was barely recognized when he died. The New York Times did have an obituary, but it was about 100 words and the only additional information I gleaned from it for this obituary is that some of his paintings were displayed in the White House for an exhibition of Black artists in the Carter administration. To say the least, Motley’s contributions have been more than recognized since his death, with major exhibitions of his own work and contributions into big exhibitions on the Harlem Renaissance and other early 20th century Black art.

Let’s look at some of Motley’s work:

Archibald Motley is buried in Mount Olivet Catholic Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois.

If you would like this series to visit other Black artists, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Horace Pippin is in West Goshen, Pennsylvania and Minnie Evans is in Wilmington, North Carolina. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.