Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,774

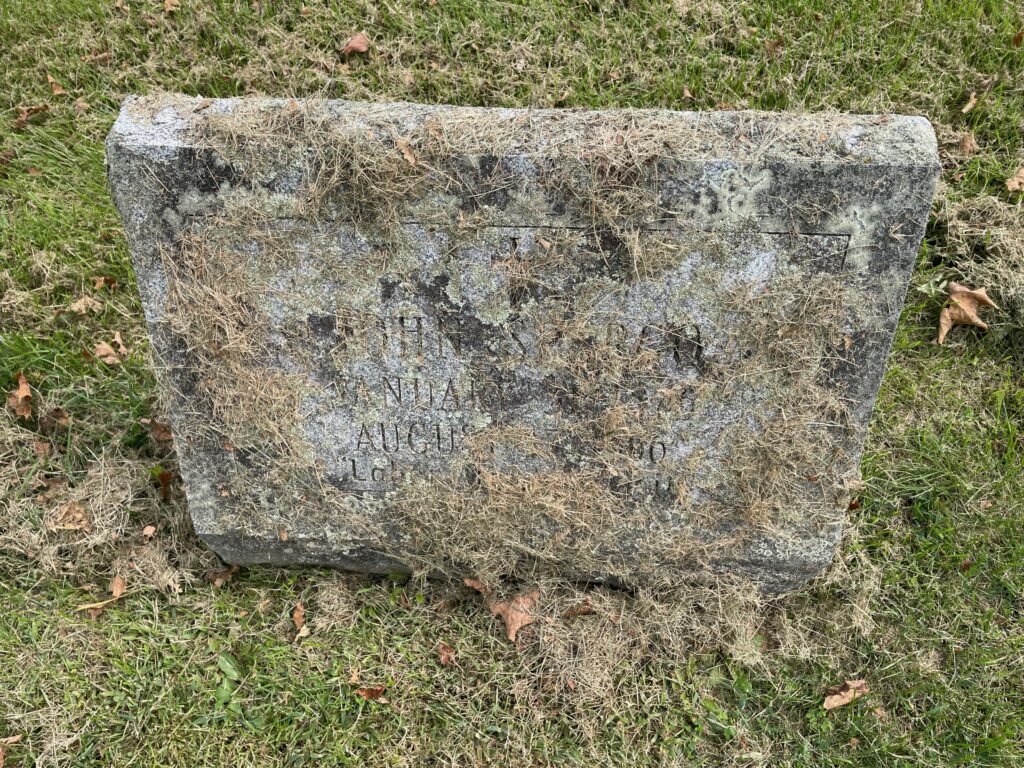

This is the grave of John Spargo.

Born in 1876 in Longdowns, Stithians, Cornwall, England, Spargo came from the skilled working class. He was trained to be a stonecutter. He was a good Methodist too, and early in his life became an ordained Methodist minister. Like a lot of young people in the late nineteenth century, Spargo became attracted to socialism. For him, the conversion experience was Henry Hyndman, an English Marxist who was the first important translator of Marx into English and who wrote significant works himself, though he was also an avowed anti-Semite, so not a great guy.

Anyway, Spargo was mostly self-educated, managing to take a couple of classes at a kind of Oxford extension program but that was it for any kind of higher education. He moved to Barry Docks in Wales to work as a stonecutter, was a big time volunteer for the Social Democratic Foundation, which was Hyndman’s Marxist group, and rose quickly in the British leftist labor movement. He soon became Trades and Labour Council, edited the local leftist newspaper, and then was selected for the National Executive Committee of the SDF. In 1900, he was deeply involved in the creation of the Labour Parlimentary Representative Committee, an amalgamation of groups that was an important precursor to the creation of the Labour Party.

But then Spargo felt that this was too much compromise with mainstream politics. Hyndman considered this all a huge sellout from the proto-Leninism he aspired to (I love the history of left fractionalism anytime one might actually win something) and Spargo went along with his hero. But then he made a different decision–he moved to the United States in 1901. At first, this was just for a lecture tour. As he was a good speaker, some socialists in the United States had seen him and thought he would be good to hear. He had just gotten married and he and his wife saw this as both a fun honeymoon and a chance to create the revolution. So why not go?

But the lecture series did not work out. Will it shock you to know that the socialists did not have their shit together? Hardly any of the planned lectures happened. Spargo got a job shoveling snow in New York to eat. He did get to know New York’s socialists though and became close to people in the Socialist Labor Party such as Morris Hilquit. He didn’t have the money to go back to England and then by the time he did, he decided to stay. He edited a socialist magazine in New York and finally, he did have success as a paid socialist lecturer. Spargo also used the time traveling around the nation to have sex with as many hot young socialist women as possible, to the point that this became part of his public reputation. At one point, he had to borrow $200 from Hilquit to pay off a blackmailer who had found out something or another that was genuinely damaging info.

I could go into the endless details of left factionalism; they are very well documented by the kind of lefty intellectual who is really into the vagaries of various early twentieth century socialist movements. That stuff never moved me much as a historian. He was heavily involved in the Socialist Party, but began to move to the right on some issues as early as 1905 or so and continued moving that way for the next six decades. First, he moved away from direct action socialism toward building up educational institutions to educate people on socialism. Well, that’s fine. He even started a settlement house in Yonkers, New York. He wrote some well-received books on child poverty and an important biography of Karl Marx in 1908.

Spargo moved to Vermont in the 1910s for a rural life to deal with a heart issue. He remained the head of the right-wing of the socialists for awhile, but by World War I was pretty well anti-socialist entirely. He supported American intervention in World War I, which led him to leave the SP entirely, and worked closely with American Federation of Labor head Samuel Gompers of this version of labor internationalism. He was horrified by the rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia and spent the rest of his life as an overt anti-communist.

Now, by the 1920s, Spargo wasn’t particularly relevant. He wasn’t really much involved with the labor movement after this; some old labor commies would become extreme anti-communists, but Spargo was at heart an intellectual, not a labor man, unlike Jay Lovestone, who usually is the person held up as the model of the former leftist turned far rightist. But at least Lovestone always believed in unionism. Spargo developed his own theories around what he called “socialized individualism.” His embrace of American individualism soon led him to turn his back on the socialized part of that entirely. By 1924, he was a loud support of Calvin Coolidge for president. When Herbert Hoover won the presidency in 1928, there was talk about bringing Spargo in as Secretary of Labor. To say the least, the Great Depression did not change Spargo’s politics. Maybe it was living in Vermont, one of only two states to never vote for FDR. That flinty, stingy, cheap individualism of old New England became perfect for Spargo, who loathed the New Deal and who came to love the House Un-American Activities Committee, even in its original form in the late 30s under the fascist clown Martin Dies. He lived forever and became an expert in ceramics when he wasn’t hating the left, writing a few books on the topic. By 1964, a very old Spargo was a loud Barry Goldwater supporter.

Spargo died in 1966, at the age of 90.

John Spargo is buried in Bennington Center Cemetery, Bennington, Vermont,

A word about this kind of granite grave and the care of modern graveyards. There are more important things in the world, but the modern lawnmower and a very prominent style of grave do not go well together, as you see. The riding mowers used by cemetery caretakers spray grass everywhere and it sticks to granite, making the gravestones almost impossible to read and quite often nearly impossible to find. I don’t imagine a social movement to change cemetery maintenance practices since Americans have a fetish for very short grass, but it is not the best for this series, not to mention my usual terrible photography skills.

If you would like this series to visit other people involved with the Socialist Labor Party, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Arnold Petersen is in Queens and Frederic Heath is in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.