Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,766

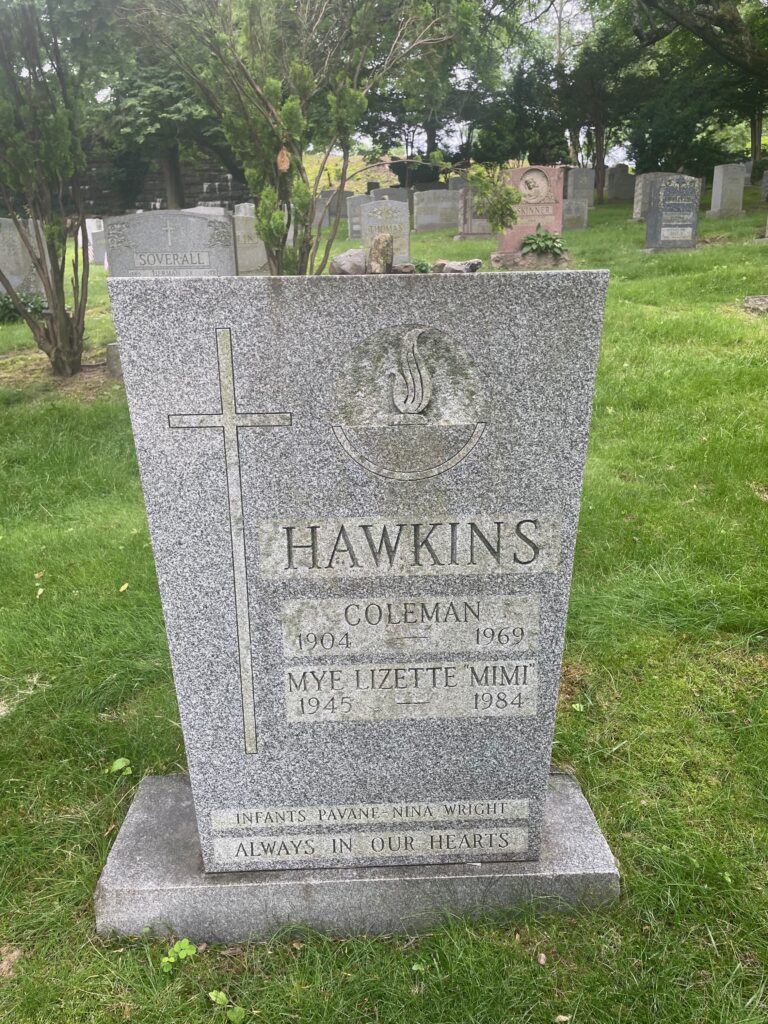

This is the grave of Coleman Hawkins.

Born in 1904 in St. Joseph, Missouri, Hawkins was introduced to music as a child. His parents had him start playing the piano at the age of four. Later he picked up the cello and then the saxophone. He stuck with the last, which was, uh, a good call. By the time he was 14, he was playing in clubs around eastern Kansas. The family was somewhat mobile during the late 1910s, as were many Black families, and he spent some time in high school in Chicago and then in Topeka, He was able to attend Washburn College for a bit as well, studying musical composition.

In 1921, Mamie Smith hired the kid Hawkins into her Jazz Hounds. An amazing career began. In 1923, now based in New York, he joined Fletcher Henderson’s Orchestra. He stayed with Henderson for a very long time, unusual for the big band era. He served a full eleven years with Henderson and it was an education. Of course he played with other people during this time as well, when Henderson wasn’t on the road. That included with Louis Armstrong in 1924 and 1925, as well as with the Mound City Band Blowers, the rare integrated group based out of St. Louis. Hawkins expanded his instruments to bass sax and clarinet in these years too. Over the years, he became a star soloist with Henderson and began to be featured on recordings. Arguably, he became the first really important saxophonist in jazz history while he was with Henderson. Here’s a quote from his New York Times obituary on this point:

During Mr. Hawkins’s career, which spanned almost half a century, he created the first valid jazz style on the tenor saxophone, influenced countless saxophonists and was in the vanguard of jazz development.

There were saxophonists in jazz bands before Mr. Hawkins began to develop his manner of playing in the mid-1920’s. But they were using a slap-tongue effect, which resulted in a chickenlike sound, reflecting the prevalent feeling that the saxophone was essentially a comic instrument. Mr. Hawkins, who had been using this technique himself, found and developed resources in the saxophone while he was in Fletcher Henderson’s Orchestra at Roseland Ballroom between 1924 and 1927.

He used a big tone and a heavy vibrato. His swaggering attack drove along relentlessly through intensely rhythmic, choppy phrases.

I’m not really enough of an expert on this subject to be able to offer much analysis of the claim and would be curious to see what our many jazz experts around here have to say. Hawkins was also known for his incredible volume, often said to be the first saxophonist to really turn up the sound to become the lead in a jazz orchestra, during a period when the trumpets tended to dominate.

In 1934, Hawkins decided to try Europe. Initially, he was with Jack Hylton, the English bandleader, but pretty quickly he became a solo act. He stayed in Europe for most of the next five years. In 1937, he recorded with Benny Carter and Django Reinhardt in Paris. Of course, being in Europe meant missing out on the fast-changing jazz scene in the United States. So when he returned in 1939, he had to make a statement to assert his dominance as a saxophonist. There was no shortage of competition with the rise of Lester Young, Ben Webster, and others. Well, he did. On October 11, 1939, he played one of the most important solos in jazz history. Playing at Kelly’s Stables in New York, he did the standard “Body and Soul,” where he ignores almost all the melody and uses it as a moment to improvise. This became one of the founding statements of the be-bop movement that would come later and blew everyone’s mind. Hawkins was back.

Mostly in the 40s, Hawkins worked with small groups, not ignoring the big band era still popular, but rather handling more manageable groups. He became perhaps the most important pioneer of be-bop at this time and his 1944 session where he brought in a young trumpeter named Dizzy Gillespie, as well as Don Byas, Clyde Hart, Oscar Pettiford, and the great Max Roach, is often considered to be the first true be-bop session. That became the great album Woody ‘n You. He blew everyone’s mind, including Miles Davis, who later said it was Hawkins who taught him how to play a ballad and let’s just say the student was pretty good at it. He started soloing a lot more at the beginning and ends of songs. He was also deeply immersed in the classical world and brought Bach especially into jazz for perhaps the first time.

Over the next fifteen years, Hawkins played with effectively everyone in jazz, both in the U.S. and Europe. Hank Jones, J.J. Johnson, Fats Navarro, Roy Eldridge, Jo Jones, and of course Thelonious Monk. He and Monk had played together a bunch back in 1944, but then didn’t really for a long time. But in 1957, they reunited for the session that became Monk’s Music, with John Coltrane as well. That session also provided half the tracks for Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane, which was not released until 1961, but is a legendary set of recordings. But it is worth noting here to some extent that Hawkins by this time was playing the secondary role behind the great Coltrane. Of course a lot had changed in jazz over the past twenty years. In fact, Hawkins was a big reason for that. Respect for Hawkins was enormous. Said Lester Young, “As far as I’m concerned, I think Coleman Hawkins was the president, first, right? As far as myself, I think I’m the second one.” Can’t have higher respect than that! Generally during these years, Hawkins was almost a solo performer. He really didn’t have anything like a consistent band and just set up with whatever rhythm guys were around,

But Hawkins stayed pretty relevant into the early 60s. In fact, some of his recordings from this era and among his very greatest. He was a regular at the Village Vanguard in these years and was really at the peak of his game. He was on Max Roach’s astounding We Insist! album, with Abbey Lincoln. He and Duke Ellington finally recorded together in 1962 for Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins, one of the finest albums in both of their careers and which of course included a lot of the Ellington Orchestra too. Hawkins’ 1962 album Here and Now is another excellent contribution to his discography. Then in 1963, he and Sonny Rollins got together for Sonny Meets Hawk, which at the very least is a quite solid contribution to both of their careers.

Unfortunately, Hawkins was always a pretty heavy drinker and by the 1960s, it really started affecting his career. After about 1963, he was just about finished as a useful artist. He recorded nothing after 1967 and died of liver disease in 1969. He was 64 years old.

Coleman Hawkins is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, The Bronx, New York.

Let’s listen to some Hawkins:

Hawkins was the first Critics Pick in the Downbeat Jazz Hall of Fame, which is a pretty flawed list overall, but is as good as we can get and certainly no one is going to question Hawkins’ place in it. That was in 1961. If you would like this series to visit other members of said HOF, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Bix Beiderbecke, selected in 1962, is in Davenport, Iowa, and Art Tatum, selected in 1964, is in Glendale, California. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.