Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,744

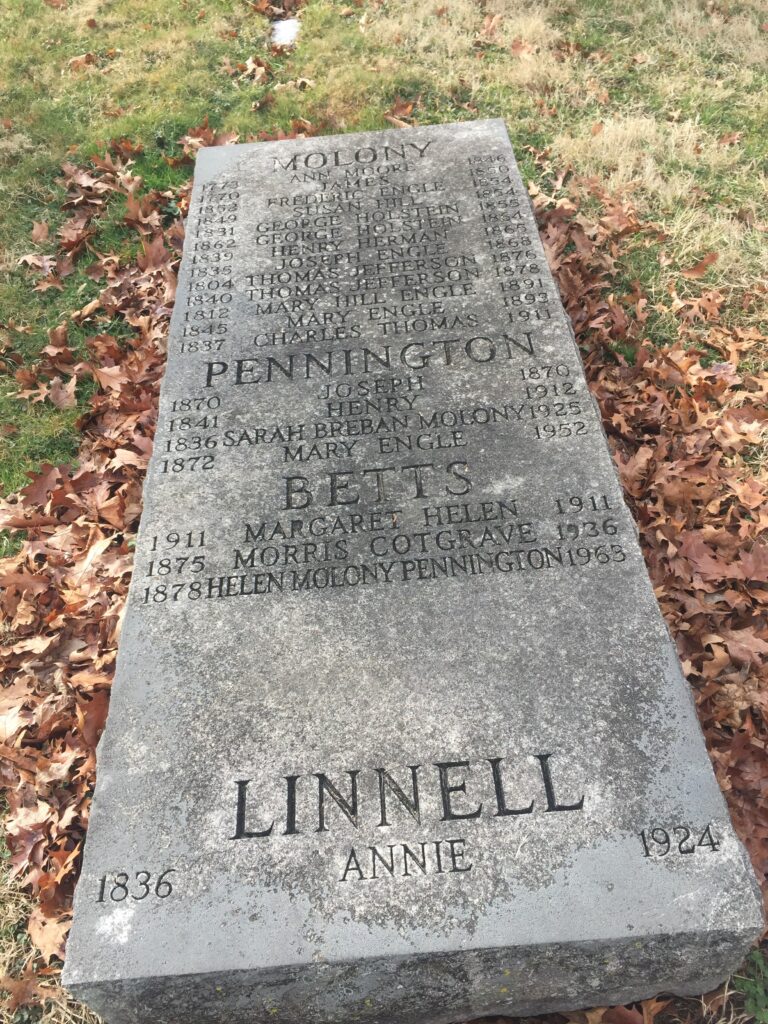

This is the grave of Mary Engle Pennington.

Born in 1872 in Nashville, Pennington grew up in Pennsylvania. Her parents were Quakers and I don’t know why they moved to Tennessee, but they wanted to be back home. Her parents valued the education of girls and encouraged her when, at the age of 12, she checked out a library book about chemistry and became interested in the topic. She was a brave girl. She went over to the University of Pennsylvania and asked some chemistry professor for help with the terminology. He was like, kid, I don’t have time for this, you are too young, come back when you are older.

Well, she did. She enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania in 1890 and finished her undergraduate degree in 1892, majoring in Chemistry with minors in Zoology and Botany. Except for one thing–Penn did not give degrees to women. They gave them “certificates of proficiency.” And yet, they then admitted her to their PhD program and she earned that doctorate in 1895 and that wasn’t no certificate of proficiency either. Pennington had some post-doc type things, including one at Yale in physological chemistry.

But the fact was that women simply were not going to get the good jobs in these fields. It was a sexist world. But this was also the Progressive Era and women were creating their own professions. Pennington was a piece of this. She tapped into the growing concern about women’s health and since men didn’t want to touch this subject with any seriousness, it opened the door for women. So in 1898, Pennington started her own lab. The Philadelphia Clinical Laboratory dedicated itself to food safety, especially in the milk supply, a big concern for women at this time, given all the adulterated milk entering the cities. We can’t overstate the importance of this–bad milk was a leading killer of babies and small children. It caused diarrhea their digestive tracts just could not handle. Milk became a major issue for female reformers, allowing them to make the nation better while also framing it entirely within maternal instincts, creating more space for them to operate in both science and public policy. Pennington was able to engage in investigations of dairy farms outside of Philadelphia and helped standardize routine farm inspections for the milk supply. There was also the issue of ice cream. A common job for poor kids in the summer was selling ice cream out of pushcarts. Pennington realized none of this was regulated at all and while I have little doubt she’s rather see those kids in school, her emphasis was on the consumer safety side of this. She took samples that demonstrated clear bacterial infection to the ice cream suppliers, who saw the threat she offered them and they agreed to higher safety standards in the production of the ice cream.

Well, Pennington proved quite effective at food safety and as the government started taking this more seriously with the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, she found government work. That was extremely unusual for any female scientist. She got a job at the Bureau of Chemistry in 1905, which was led by Harvey Wiley. Now, men were sexist but not all men were sexist and like everything else, we have to remember when he say that so and so was a product of their time that some people were forward thinking. Wiley was evidently one of them, for he thought Pennington excellent and when the Food and Drug Administration was created, he urged her to apply as the head of the new Food Research Laboratory. She did so, but under the name M.E. Pennington, so as to hide her gender. She got the job and became the first woman to head a federal lab. Pennington’s work of course had contributed to the evidence needed for the new food safety laws. Wiley himself cited such work as critical to the laws. People credit Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, and of course that was a key point, but it was a lot more than one person with one book telling one very gross story. We always do oversimplify these things to tell pat narratives about the past and I don’t blame anyone for this, but it does erase people such as Pennington.

In the next decade, Pennington became perhaps the top food safety scientist in the nation. Milk was certainly at the top of her list but so was chicken. Refrigeration had shifted American meat preferences. The U.S. was a pork nation until the creation of the refrigerated rail car because it was the one meat you could trust if it was salted. There was a lot of fear of refrigerated meat when it appeared on the market. Beef was first, in the late 19th century. It took awhile for proof of safety to allow it to win out, eventually surpassing pork. It would take a long time before the U.S. became a chicken dominate nation, as we are today. Poultry is really sketchy if not shipped correctly. Pennington became the leader in ensuring the proper way to freeze and store chickens, helping build up the market for poultry. She led investigations on proper refrigerated box car designs, for example. She and Howard Castner Pierce also won a patent for inventing a poultry cooling rack.

Overall during Pennington’s career, she received five patents, including creating a sterile food storage container and a method of freezing eggs. I can’t say I’ve really ever heard of freezing eggs. I guess no one would have a reason to do that today. Plus eggs are so much more available than they were a century, when they were more seasonal in nature. She also pioneering frozen fish technology, basically pioneering flash freezing fish and getting that to market as fish filets. Can’t say I’d eat frozen fish filets today or, God forbid, fish sticks, but this was a huge part of the American food market for a very long time and of course people do still eat this today.

During World War I, Herbert Hoover brought her on board as par of his War Food Administration. In 1919, Pennington left the government to work for American Balsa, a manufacturer of refrigeration units. She then started her own consulting business in 1922 and ran that for the next 30 years. She created the Household Refrigeration Bureau in 1923, an organization to create and support proper refrigeration practices. She became a consultant and supporter of the National Association of Ice Industries, basically a trade group of ice distributors for the iceboxes that people used before the arrival of electric refrigerators. For the NAII, she wrote pamphlets about food safety, such as The Care of the Child’s Food in the Home in 1925 and Cold is the Absence of Heat in 1926.

Pennington died in 1952, still working. She was 80 years old.

Mary Engel Pennington is buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Pennington is a member of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers Hall of Fame. And what a Hall of Fame!!!!! As an aside, one of the things I love about doing the grave series is learning about stuff like this. Anyway, if you’d like this series to visit more illustrious members of this august body, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. John Engalitcheff, Jr., who evidently invented a lot of the technology used in air conditioning systems, is in Baltimore and Reuben Trane, who was involved in early 20th century cooling systems, is in LaCrosse, Wisconsin. Damn, this is going to rake in the donations! Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.