Economists’ Flawed Use of History

Because of overlords who love to turn DATA into a fetish, anytime an economist demonstrates something historians have known for twenty years, it gets headlines in major papers because NUMBERS. Me, I don’t even know what data is at this point, but I do know that numbers only tell us very skewed stories about human society, very much including the economy. Just as one example, take the completely skewed perception people have of the economy right now versus how it actually is and how this is impacting the election. I argue for understanding the economy as culture as much as anything else because all the DATA in the world isn’t going to tell us a damn thing about how people articulate and act on their economic feelings.

Well, the Nobel in Economics just went to three economists named Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson. They won for some work in historical economics. This has been a big thing in economics lately, using history. That’s fine, but historians hate this work because it is bad history. That’s true of much of the smaller studies and according to the historian of capitalism Brendan Greeley, it is very much true of these Nobel winners too.

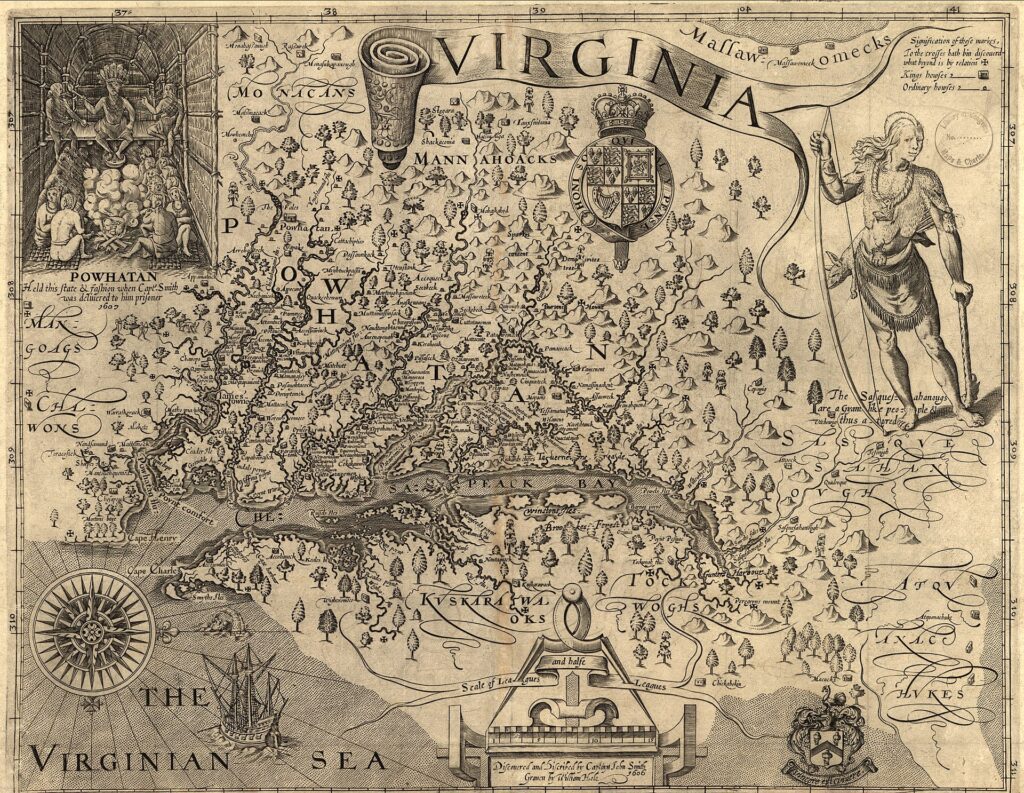

In Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson’s 2012 summary of their work on institutions, they use late 17th century England, Barbados and Virginia as examples. England and Virginia became inclusive: property rights, legislative assemblies, limited but slowly expanding franchise. Barbados became extractive, relying on enslaved labour to produce profits for a small elite.

These descriptions are true but insufficient, because England, Barbados and Virginia were all part of the same system. The same captive domestic market, protected by tariffs, sent slave tobacco and slave sugar through factors in the colonies and merchants in London and Glasgow.

The shape of this captive market was clear to John Mair, who wrote a chapter of instructions on how to account for the enslaved and the sugar trade through factors in Barbados and Jamaica, explaining how that trade “not only employs multitudes abroad in the colonies, but cuts out work for a vast deal of people at home.” Both manufacturers and merchants, he wrote, “are hereby not only maintained, but many of them enriched.”

London merchants and Barbadian planters, well represented in Parliament, became powerful advocates for inclusive institutions in Britain not in contrast to the extractive institutions on the other side of the ocean, but because of them.

It is easy to pick on Nobel Prize winners from afar. If they’re so wrong, it should be easy for you to prove it and claim your own trip to Stockholm. This question of just how much extraction contributed to England’s financial and industrial revolutions, though, is one of the most openly and furiously contested problems of early modern Atlantic history.

It offers another well documented, compelling explanation for the inclusive institutions of early-modern Britain. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson have encountered this question — it’s right there in their footnotes. They just don’t seem to think it matters.

They are by all accounts nice, thoughtful guys, so the problem doesn’t seem to be arrogance or wilful blindness. Rather, this inability to see how London, Virginia and Barbados function within the same system is, ironically, an institutional problem within the profession of economics. Economists are really good with numbers. This is important. Numbers matter, and the ability to infer how they affect each other matters, too. Some things, however, don’t seem to respond in obvious ways to numbers, or sometimes the numbers are constrained by things that are hard to measure.

It’s helpful to think of these things as institutions, the habits of mind and the state that shape markets. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson are right to see the importance of institutions, and they were right to drag the rest of their profession in their direction. The problem is that institutions are exactly the parts of markets that are inherently resistant to discovery through numbers.

Luckily, there are other professions that find, train and accredit the kinds of people who are good at understanding the political and cultural forces that drive institutions. These professions are the rest of the social sciences — sociology, history, anthropology, political science. Economists are socialised to look down on the rest the social sciences as unserious, but it’s a funny ol’ thing when you reach the end of numbers and bang into an institution. You need new tools, exactly the ones you were told lacked rigour. This week economists have been congratulating themselves on following Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson into institutions. They are, in effect, proud to have discovered the rest of the social sciences.

It would be churlish to gatekeep the economists out. The study of history, for example, is just the application of eyeballs to paper over time. All should be welcome. But it’s reasonable to expect curiosity and discipline, to ask the economists to sit still long enough to encounter all the basic questions lobbed at every first-year grad student. Mastery of these questions is not just a status signifier; it shows that you understand what has already been said, so you can contribute something new and meaningful.

Economists would never dream of approaching the nature of the firm without explaining carefully where they stand on Ronald Coase, for example. But this is exactly what Acemoglu and Robinson do in the opening chapter of Why Nations Fail.

But, but, DATA!!!!!!!

And lets you think this is just different disciplines taking shots at each other, when you put one discipline on a pedestal because it provides answers in a way that appeals to a particular subspecies of overlords, you are erasing the many different ways of knowing the world. There is nothing wrong per se with the field of economics. There is however something very wrong about pretending to be historians without doing even the most basic homework from the historians and there’s something really wrong with the smugness with which many economists approach their cousin disciplines.