The State of Unions

On Labor Day, we should look at the state of unions. Chris Bohner has a deep dive and despite the public support for unions, nothing has really changed.

“We’re organizing like never before!” That’s what the AFL-CIO says, but is it accurate? While data is not readily available for public sector workers, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) tracks the number of workers involved in union elections in the private sector. In 2023, approximately 93,000 workers participated in an election for union representation, up from 63,000 workers in 2022. And 2024 is on pace for approximately 107,000 workers voting on union representation.1

The increase in union representation elections is encouraging, but if you step back and look at the number of elections in relation to total employment, the challenge becomes clearer. In 2023, the 93,000 workers participating in union elections represented just 0.09% of the 108.4 million production and nonsupervisory employees in the private sector. In 2024, the percentage is projected to be about 0.10% of all workers. In other words, only one-tenth of one percent of eligible U.S. workers in the private sector are getting the opportunity to vote for a union.2 This pace of organizing is not enough to keep up with employment growth, let alone meaningfully increase union density in the private sector (i.e. the percentage of all workers represented by a union).

Looking at the historical data, it’s harder to support the contention that labor is “organizing like never before.” The 2023-2024 election rate of 0.09-0.10% is just a smidge higher than the 2010 decade and significantly lags the average election rate of 0.17% in the 2000 decade.

But imagine if labor put on its seventies bell-bottom jeans and started organizing one percent of eligible workers as unions did in the 1970s, not the current one-tenth of one-percent rate. Instead of 107,000 workers voting for a union in 2024, the number would be more like 1.1 million workers.

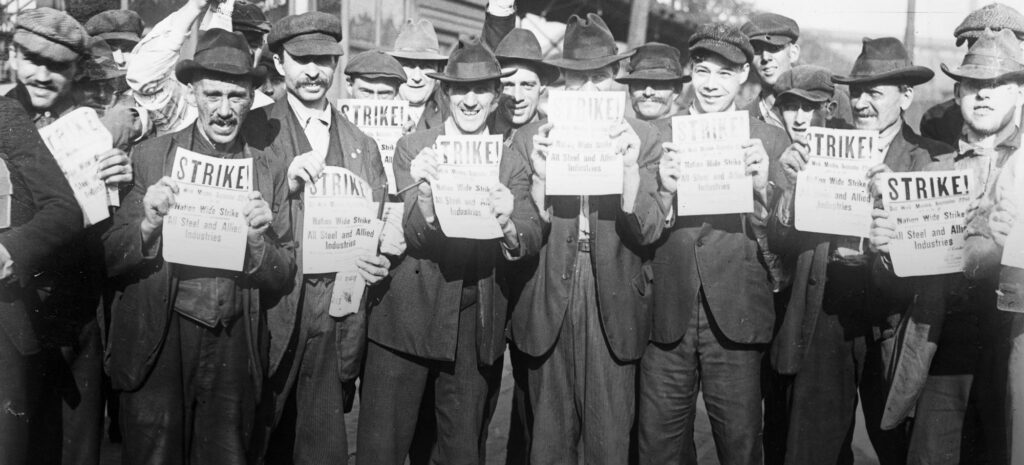

And then there’s strikes:

Through June 2024, total compensation for union workers is up 6% year over year, while non-union workers have only seen a 3.6% increase over the same period. That’s the good news.

The disappointing news is the strike “wave” of 2023 appears to be a blip rather than an emerging trend. In 2023, approximately 459,000 workers went on strike, including 50,000 UAW members at the Big 3 automakers and 160,000 SAG-AFTRA members employed by the entertainment industry. Through late August 2024, approximately 106,000 workers have been on strike, significantly lagging the 2023 total strike numbers.3 While additional union contracts are expiring in the fall — most notably the Machinists and Boeing — it is likely that 2024 will fall short of the 2023 strike numbers.

Looking at strikes as a percentage of the non-farm workforce, the Red for Ed strikes of 2018-2019 and the 2023 strikes were the largest strikes dating back to 2000, representing about one-third of one percent of the total workforce. However, as with the organizing data, the 1970s were marked by a vastly higher proportion of workers on strike as a percentage of the workforce, reaching nearly two percent of all employees. If two percent of workers went on strike today, roughly 3.1 million would be picketing. Attending all of those picket lines would surely be a travel nightmare for the presidential candidates and faux populists rushing to attend.

Now, Bohner has some interests that I don’t have, particularly around union democracy issues, about which I am ambivalent given that there’s little evidence that more direct union democracy in international decision making actually leads to better decisions. And some of the tone is a bit snarky for my tastes when it comes to discussing labor. But I do agree that we need to be realistic where we are as a movement. There are good things happening. But honestly, they aren’t that much better than before. They just have a bit more support. That’s good, but that’s a long way from really turning around the labor movement.