Tim Walz and Holocaust education

In 1993, when he was a 29-year-old high school teacher in a small Nebraska town, Tim Walz designed a classroom project in which his students were asked to try to predict what country in the world was most likely to be the site of the next genocide. Their prediction: Rwanda.

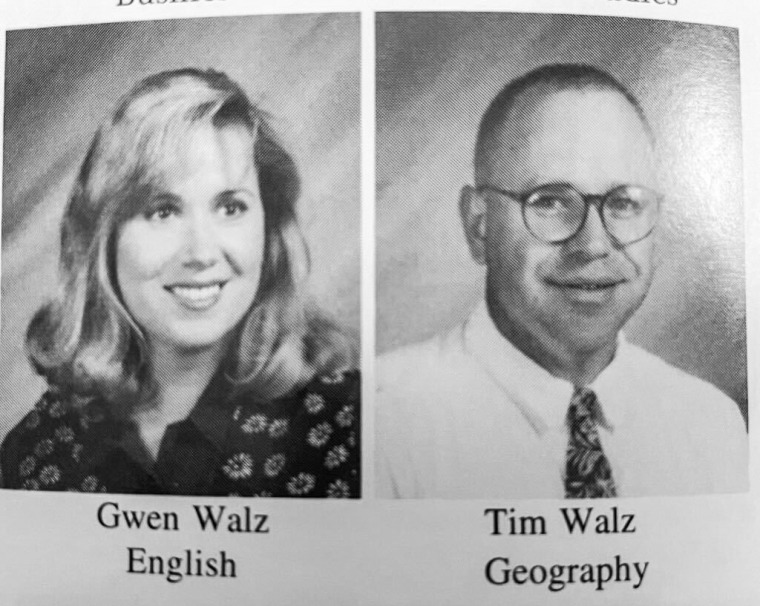

In 1993, while teaching in Nebraska, he was part of an inaugural conference of US educators convened by the soon-to-open US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. Eight years later, after moving to Minnesota, he wrote a [Master’s] thesis arguing for changes in Holocaust education. And as governor, he backed a push to mandate teaching about the Holocaust in Minnesota school.

Through it all, Walz modeled and argued for careful instruction that treated the Holocaust as one of multiple genocides worth understanding.

“Schools are teaching about the Jewish Holocaust, but the way it is traditionally being taught is not leading to increased knowledge of the causes of genocide in all parts of the world,” Walz wrote in his thesis, submitted in 2001.

The thesis was the culmination of Walz’s master’s degree focused on Holocaust and genocide education at Minnesota State University, Mankato, which he earned while teaching at Mankato West. His 27-page thesis, which JTA obtained, is titled “Improving Human Rights and Genocide Studies in the American High School Classroom.”

In it, Walz argues that the lessons of the “Jewish Holocaust” should be taught “in the greater context of human rights abuses,” rather than as a unique historical anomaly or as part of a larger unit on World War II. “To exclude other acts of genocide severely limited students’ ability to synthesize the lessons of the Holocaust and the ability to apply them elsewhere,” he wrote.

He then took a position that he noted was “controversial” among Holocaust scholars: that the Holocaust should not be taught as unique but used to help students identify “clear patterns” with other historical genocides like the Armenian and Rwandan genocides.

Walz was describing, in effect, his own approach to teaching the Holocaust that he implemented in Alliance, Nebraska, years earlier. In the state’s remote northwest region, Walz asked his global geography class to study the common factors that linked the Holocaust to other historical genocides, including economic strife, totalitarian ideology and colonialism. The year was 1993. At year’s end, Walz and his class correctly predicted that Rwanda was most at risk of sliding into genocide.

The Holocaust and genocide in general are extraordinarily important topics that, to the best of my recollection, were never once mentioned during my the years of my primary and secondary education in the 1960s and 1970s. Walz’s decades-long commitment to making sure students learn something about these things, first in his own classroom, and eventually in the state where he became a member of Congress and then governor, is both a very good thing in and of itself, and a sign of what an interesting and remarkable person he is — the precise opposite of the legions of empty suit credential mongers who infest national politics, while displaying a passion for practically nothing other than their own personal ambitions.