This Day in Labor History: June 5, 1944

On June 5, 1944, white workers at an airplane plant outside of Cincinnati went on strike over Black workers being promoted. Happening a mere day before the U.S. invaded France to drive out the Nazis, it led to a lot of condemnation of the strike, but also represented something that was far too common during the war, which were wildcat strikes over the integration of work.

When I get into conversations with people about union democracy, I hear a lot of claims of things such as “any truly democratic union is going to have progressive politics.” I have heard this stated by big whigs in the labor reform movement. Well, that could happen. But historically, the one thing that has bonded white workers together is white supremacy at the workplace and while today is not a century ago, I am not so sure that actual democracy in the workplace couldn’t lead to some of the same results. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first major piece of federal legislation that came out of the labor movement and if that wasn’t a grassroots worker revolt, the term has no meaning. I am highly suspicious of anyone who thinks the general public would actually have their personal politics if only real democracy took place.

Well, the defense of white supremacy at the workplace went on far longer than the nineteenth century. World War II brought great movement of workers around the country and to new areas too. This is when the development of large factories on the West Coast took place and, not surprisingly, when sizable Black populations also moved west. But of course southern whites were also leaving their impoverished homes at rates similar to Black southerners. They brought their racial politics with them. It did not take very much convincing for lots of white workers in the North to take on those southern racial politics, since they mostly felt them already. That was as true for Poles and Czechs as it was for any native-born white. Anti-blackness has long existed as a way for European ethnics to claim whiteness, as the historian David Roediger has shown in such detail in his histories of the 19th century Irish.

The New Deal of course brought a lot to the American worker. That was true for workers of all races. But there’s no question that white workers benefited more. Federal administrators were so worried about offending southern racial norms that they unwittingly instituted new forms of segregation at the workplace, especially in the more grunt labor type jobs with the Tennessee Valley Authority that previously weren’t so segregated, but became more so after the TVA implemented the practice. Most relief programs were administered by locals and if those locals were super racist, well, good luck being Black and getting much relief. The New Deal also saw the rapid expansion of the union movement. But these unions were made up of the real American working class, not some fake leftist one. There were leftist unions that promoted racial equality and sometimes they even succeeded, especially with the United Packinghouse Workers. But many others promoted full-fledged white supremacy.

The big industrial unions in the CIO were at least verbally anti-racism. But their members did not always listen to their union leaders on politics. For example, as the historian Thomas Sugrue explored, when Detroit allowed a public housing project to be open to Black people, whites at the local level abandoned the Democratic Party for a time, even though FDR had gotten them their union. The outrage over integration led to voting for Republicans in the city itself. So it was not surprising that all this moving around and all this new work would lead to racial tensions on the job.

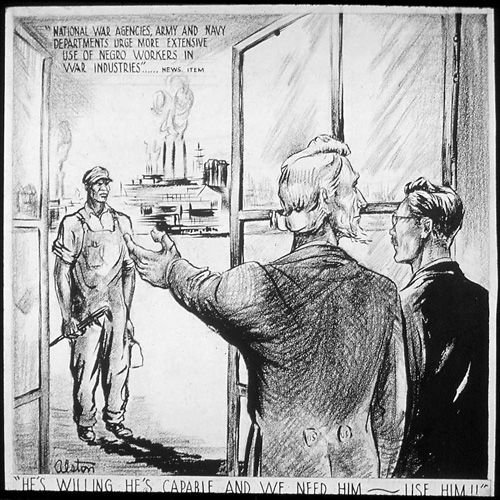

Now, FDR didn’t care much about the condition of Black people. In that, he was a good old school Democrat. He even named his favorite Confederate nostalgia author ambassador to Spain! Eleanor pressed her husband hard on these issues, sometimes to some success. But it was really A. Philip Randolph’s March on Washington movement that forced Roosevelt to do something about racism in the workforce. Determined not to have America’s racial problems broadcast to the world as the nation prepared to fight fascism, FDR issued an executive order in 1941 forcing the integration of workplaces receiving defense contracts, which was most large American workplaces. He then created the Fair Employment Practice Committee to enforce it.

The FEPC was pretty weak and advances for Black workers remained awfully slow, but they did happen. So it isn’t too surprising to note that there were a number of hate strikes in the war over this, with white workers freaking out and walking off the job in protest of a Black worker being promoted. The most famous of these was in 1943 in Detroit, when Packard, whose owner was a really truly horrible human being, intentionally promoted Black workers to generate hate, hoping to get the union out of his factory entirely. UAW leadership stood up for Black workers in this case, angering a lot of the Packard workers and the strike was suppressed. Again, this was real union democracy at the local level. It was just to promote horrible things.

There were lots of other hate strikes too. Miners in Butte, Montana engaged in one in 1942. Philadelphia transit drivers had another in 1944. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated at the time that between March and May 1943 alone, over 100,000 man-days of war production were lost over brief hate strikes. The second most prominent hate strike was in Cincinnati on June 5, 1944. The Wright engine plant made, naturally enough given the name, airplane engines. When the company promoted a few Black machinists, these UAW members (the UAW’s actual name is United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America) walked off the job.

The UAW did crack down on its own workers here. It issued a statement reading, in part:

“The strike … provoked by a handful of individuals is a blow at our boys invading Europe … The UAW is absolutely opposed to all forms of discrimination because of race … Negro workers have fought with white workers to establish our union … Negro Army, Navy and Marine Corps fighters are on every battlefront.”

The Washington Post had two headlines on its front page on June 6. The first was the D-Day invasion. The second was the hate strike in Cincinnati shutting down airplane production to support the invasion. Both leading Army officials and UAW leaders came to Cincinnati to try and convince the workers to go back to work. They refused. They simply refused to work with Black people.

The strike only ended when the War Department stated that it would cancel its contract with the facility if the workers did not return. Thus, the owner said that any worker who did not return by that Friday would be fired. The UAW was fine with this. That did the trick. The leaders of the strike were fired, with UAW approval.

This strike hasn’t received much attention. It’s mentioned in passing in a couple of books, which is part of the reason why this post is much more context than detail. But let’s remember that democratic unionism is not some sort of panacea. Unions are made up of people and people are complicated, to say the least. There’s little in our history that suggests that some sort of pure democracy will lead to better outcomes, but there is plenty of leftist ideology that pretends it so.

This is the 523rd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.