The (3+3) = 6 Court

Jay Willis takes a broader view of the “3+3+3 Court”…well, not really “theory” so much as “propaganda vehicle for a very partisan Court representing the faction that has lost the popular vote in 7 out of the last 8 elections”:

The fate of the Court, 3-3-3 proponents argued, thus hinged on the three Republican appointees who fell somewhere to the right of center: Barrett, Brett Kavanaugh, and Chief Justice John Roberts. Because these three prioritize the Court’s institutional legitimacy, the hypothesis went, they would act as a check the more grandiose ambitions of their less prudent conservative colleagues, their shared policy preferences notwithstanding. In early 2021, versions of this narrative that lauded the Court’s supposed restraint were published not only by conservative law professors, but also by CNN, Politico, and The Economist. “So much for a rock-solid 6-3 conservative Supreme Court majority,” wrote Bloomberg’s Kimberly Strawbridge Robinson, a common sentiment at the time.

These predictions proved staggeringly wrong. Over the past three years, an incomplete list of the Court’s achievements includes striking down the Biden administration’s student loan forgiveness program, creating a right to possess guns in public, barring a workplace safety rule that would have protected millions of workers from a deadly pandemic, strengthening the rights of religious Americans to discriminate against LGBTQ people, abolishing affirmative action, and hacking away at what remains of the Voting Rights Act. The conservative supermajority has been so dominant that they could afford to lose a vote and still overturn Roe v. Wade, thus ending the right to abortion care after five decades of trying.

[…]

There are three basic problems with this analysis. First, by quibbling about the meaning of “important” or “politically divisive” cases, Isgur and Jens skip past the simplest available definition: how much the two major political parties care about the result. Again, when normal people talk about their objections to a “politicized” Court, they are not literally asserting that the six conservatives vote in lockstep every single time. They are referring to the sense, borne out by three years of watching the Court stuff precedent after precedent in the garbage, that the more important a case is to the Republican Party’s policy agenda, the likelier the Republican Party is to be pleased when the opinion finally drops.

This framework pretty easily resolves the ambiguity to which Isgur and Jens point: The Court decided Students For Fair Admissions as it did because Republicans oppose affirmative action and have long vowed to end it. The Court decided Biden v. Nebraska as it did because it was a chance to harm a high-profile initiative of a Democratic president whom Republican politicians had criticized relentlessly. Milligan, in which a bare majority of the Court declined to kill off Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, might be more persuasive support for Isgur and Jens’s thesis if the Court hadn’t gutted Section 2 two years earlier, with—you guessed it!—all six conservatives in the majority. By confining their analysis to the previous term, Isgur and Jens avoid having to say anything about Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the clearest example of the Court fulfilling an oft-repeated GOP promise.

Isgur and Jens also ignore what it actually means to “win” a case, erasing the distinction between conservative victories that make sweeping changes to the law and liberal victories that, at most, preserve a fragile status quo. Again, consider their examples: The student loan forgiveness and affirmative action cases torpedoed a Democratic president’s signature agenda item, and shredded a longstanding legal principle that addresses discrimination against people of color. Milligan and Brackeen merely allowed the Voting Rights Act and the ICWA to survive; Texas denied Republican politicians the power to commandeer U.S. foreign policy (for now). Sure, the conservative justices splintered in these cases, but the results are only “victories” for the left in the sense that they were not total blowouts.

As Jay says, there is no honest way of describing a Court in which Brett Kavanaugh or Amy Coney Barrett is the median vote as anything but a disaster not only for liberalism but the ability of duly elected liberals to govern, but honesty isn’t an option for Republicans strongly benefitting from their star chamber.

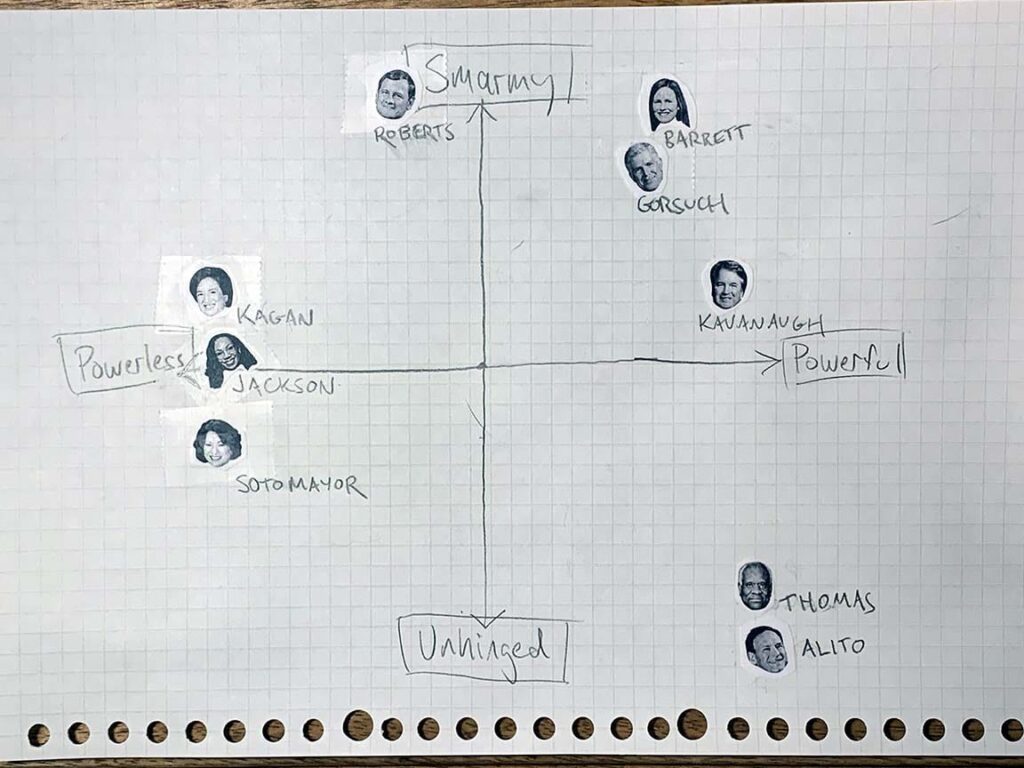

The basic left-right ideological spectrum describes the Court perfectly well, but if you insist on something more nuanced this is a better approach: