Supreme Court Fake Math

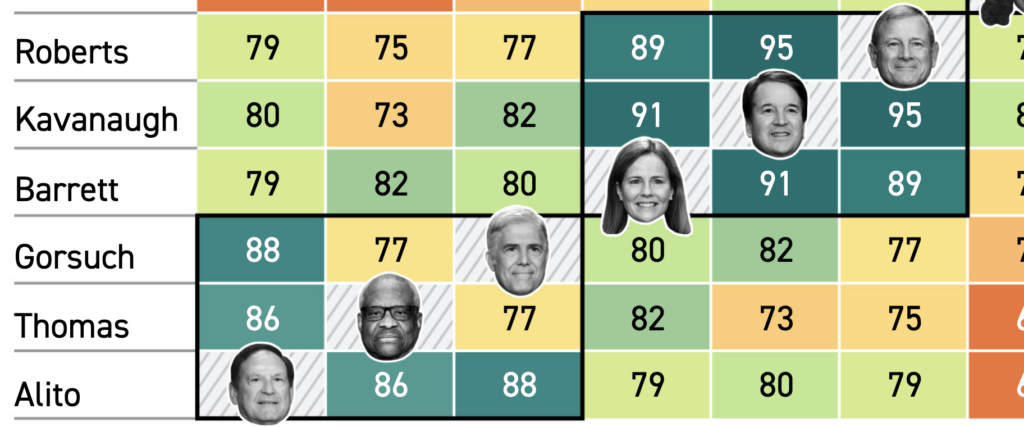

I see we have yet another attempt to deny the obvious — that there is a Republican supermajority that constitutes the most reactionary Supreme Court since 1937 — and asserting instead that there is a “3-3-3” Court of three liberals, three conservatives, and three moderates. All attempts to model Supreme Court ideology start with one issue. Even in the contemporary era, when it has near-total control of its docket and hears a relatively small number of cases, the Supreme Court still hears a lot of minor cases in which the law is toward the determinate end of the spectrum and in which the justices would be expected to have weak-to-no ideological preference. These cases often produce unanimous outcomes and don’t generally fall along typical ideological patterns when they don’t. Unless you’re trying to disprove the most extreme forms of legal realism, if these cases are not excluded from models of ideological behavior they will produce misleading data. This model excludes only the unanimous outcomes from this subset, which as they acknowledge loads the dice in favor of their conclusion:

Some might think this analysis is flawed because it gives all the non-unanimous cases the same weight instead of focusing more on the most important or most “politically divisive” cases in which all six conservatives lined up against three liberals. A critic might argue that, in those cases, political bias overwhelms all other legal considerations, including “institutionalism.”

But first, we have to agree on what makes a case important. Is it the number of people affected? Is it the economic impact? There isn’t a right answer to this question — but if one defines “important” as the most politically divisive, then it becomes circular. The most politically divisive cases wind up being … the most politically divisive, both on and off the court.

Political scientists do have some methods to try to judge the importance of cases, but I agree that ultimately some level of qualitative judgment is required. And here’s where we run into trouble:

The Supreme Court struck down the Biden administration’s student loan debt forgiveness plan. That was a 6-3 case that lined up ideologically and was by nearly any measure an important one. But if that case were decided only along the ideological axis, then why did five of those conservative justices uphold the Biden administration’s immigration enforcement plan? That decision held that states — in this case Texas and Louisiana — couldn’t sue to force the president to deport undocumented immigrants who had been convicted of crimes while in the United States? This was also considered a highly political case while it was pending before the court, but because it was decided 8-1 in favor of the Biden administration, it barely got any attention. If it had been decided 6-3 against the Biden administration, it no doubt would have been considered divisive — which just highlights the problem with the definition.

One problem that even serious political science models have a hard time dealing with is the ideological nature of the caseflow — assessing votes on the merits doesn’t tell us in itself what kind of cases the Supreme Court is taking. And here, we can see just how reactionary the Court is while just looking at the votes might make it look more moderate. The Court issued one transparently ridiculous holding –“despite the fact that nobody suing suffered any injury, we have determined that a statute giving the Secretary of Education to ‘waive or modify student loan payments does not give the Secretary of Education the power to modify student loan payments [if the Secretary is nominated by a Democratic president]” — on a straight party line vote. It rejected an even more legally ridiculous argument on procedural grounds while carefully leaving open the possibility that the courts could intervene in a core executive power at the future date. This doesn’t tell us that the Court has a 3-3-3 alignment, it tells us that when the lower courts are dominated by wingnuts conservative litigators are going to shoot their shot and they aren’t always going to win.

The Supreme Court also decided three cases about how to deal with the country’s history of racial discrimination last term. The court upheld section 2 of the Voting Rights Act which requires states to consider race in creating congressional districts. That was a 5-4 decision with the chief justice, Sotomayor, Kagan, Kavanaugh and Jackson in the majority. The court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act which gave adoption placement preferences based on tribal status. That was 7-2. And it struck down Harvard and North Carolina’s race-based admissions policies by a 6-3 vote along ideological lines. Only the last case got major headlines. Why? Perhaps because the other two didn’t line up strictly on ideological lines, and therefore were not divisive.

Citing Section 2 of the Voting Rights as a locus of moderation less than two weeks after the Court finished the job of making Section 2 essentially unenforceable on a straight party-line vote is amazing stuff. No notes.

We see the caseflow argument come up again:

These dynamics are crucial to consider when it comes to understanding the highest profile cases the high court could be deciding this term — including to what extent Donald Trump is immune from criminal prosecution or whether states can ban mailed abortion drugs. There are serious legal arguments on both sides of these questions and no controlling precedent.

There are not, in fact, serious legal arguments on behalf of the propositions that “random District Court judges can usurp the decisions of the FDA if they conflict with Republican policy preferences” or “presidents have total legal immunity unless they are impeached.” That these cases have gotten even this far shows how the federal courts have been captured by reactionary Republicans, and Court gives the conservative litigants some but not all of what they want in these cases it will not be evidence of “moderation” of “institutionalism” except insofar as “institutionalism” means that the law should play at least some role in Supreme COurt decision-making.

Incidentally, if the lead author of this piece sounds familiar, well:

Sarah Isgur, one of the Trump administration’s most dedicated practitioner’s of child separation, keeps tweeting about parenthood. One lesson I have learned from her tweets is that raising kids is easier when they have not been forcibly taken from you. pic.twitter.com/gdnvwHlczs— Isaac Chotiner (@IChotiner) December 16, 2020

Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, as moderate as forcible family separation!