This Day in Labor History: May 2, 1968

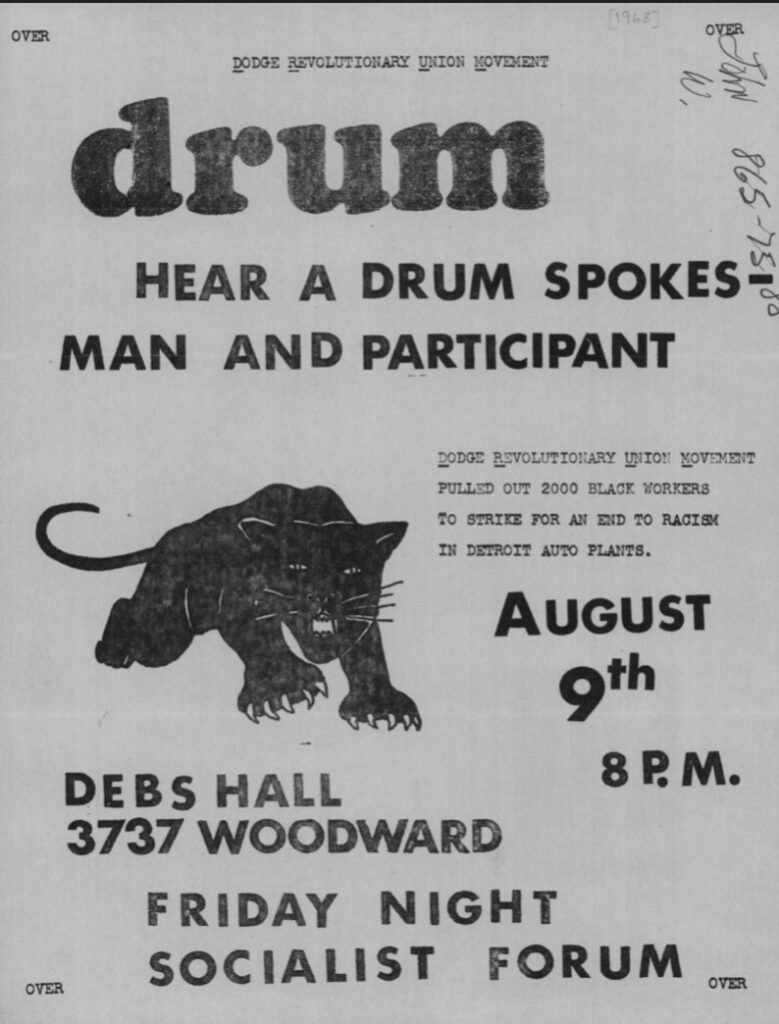

On May 2, 1968, a small wildcat strike at a Chrysler plant in Detroit led to the creation of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. This merging of Black Power and leftist unionism challenged the United Auto Workers leadership as much as it did the auto industry. DRUM did not last long, but it is an important moment in our labor history.

By the 1960s, the shopfloors of some auto plants had become increasingly dominated by Black workers. The white immigrants who had worked building up the auto industry were still around, but a lot of their kids were trying to avoid the auto plants. The job was terrible in many ways. The United Auto Workers had absolutely transformed conditions in the industry and for workers who joined in the 30s and 40s, it was completely life-changing. But the UAW never really challenged the fundamentals of the Fordist work process, which turned workers as close to machines as possible. Meanwhile, the companies had never really acquiesced to unions and the shopfloor was a constant battle between the little tyrants of the foremen and the union activists enforcing the contract. So if you had better options, a job where you might use your brain at some point might make sense. But for Black Americans, these were some of the least bad jobs available for working class people in a society where historical discrimination ran rampant, even if the Civil Rights Act and further legislation had made overt contemporary discrimination a violation of the law.

So by the late 60s, you had plants such as the Hamtramck, in the middle of Detroit but technically in an enclave within the city with its own governance known by the same name, where upwards of 70 percent of the workforce was Black. The United Auto Workers was at one point a pretty dynamic organization. But by this time, the leadership, from Walter Reuther on down, were old men who were out of touch with what the workforce had become. Regardless of the race of the workers, you had a lot of turnover around this time. The great contracts the UAW had won had allowed the generation of workers who joined the union in the 30s and 40s to retire and to do so with pensions. That began to happen in large numbers by the mid-60s. So the average age of the factory worker in the auto industry plummeted and many plants had few people over the age of 30. Their priorities were different than that of the first generation of UAW workers. Meanwhile, the leadership that also came out of that generation had little desire to go anywhere. They had sweet jobs and they thought they were representing the workers the right way.

Moreover, if there’s one thing this aging UAW leadership did not understand, it was Black Power. That was even crazier to them than the angry young workers who a few years later would strike against the union and GM at Lordstown. So they just weren’t very responsive by 1968.

Now, DRUM is one of these moments in our labor history is massively overrated. There are a few cases where, because of the political leanings of the scholars themselves, there are more books that mention an incident than there ever were workers involved in it. A classic example is of that of Judi Bari and EarthFirst!’s attempts to organize workers in northern California in the early 90s. That’s been mentioned in hundreds of books. Maybe there were 10 workers involved. I think they tried to handle a grievance case once. That’s it. DRUM is another example of this. Historians are interested in both Black Power and challenges to established labor leadership, which is why it gets talked about so much. That’s why I didn’t mention it in my Ten Strikes book and have never gotten to it in this series before now. Rather, DRUM was a brief moment.

But it’s an important moment. One of its leaders Gordon Baker, who preferred to be known as General Baker, a socialist radicalized while a student at Wayne State in the early 60s. He had gone to Cuba for awhile after graduation. He then challenged the Vietnam draft directly before taking a job in the Dodge plant to organize workers there. What he found was that the shop floors of these factories were actually quite violent. Workers beat each other up. There were knives. There were outright fights between foremen and workers. For a guy who was raised up on revolutionary violence, channeling this hate into useful political action had real potential and at the time, had a solid theoretical basis in anti-colonial activism on a global scale.

The moment that DRUM made itself known actually came from a solidarity action on May 2, 1968. A small group of white women stopped work, angry over the treatment of women in the plant and the speeding up of the assembly line. DRUM members stopped work in solidarity. Dodge fired two of the women and five of the DRUM members. Dodge blamed Baker for all of it. Meanwhile, Baker and his colleagues worked with the city’s Black radical paper Inner City Voice to promote all the terrible things going on in the Dodge plant. DRUM never really did extend far past this plant, but between 1968 and 1971, it was an important force in labor relations here.

UAW leadership hated DRUM. In fact, Local 3 filed a grievance against Dodge for allowing DRUM to pass out leaflets criticizing the leadership. It organized a slate to go up against Local 3 leadership, which was headed by an aging white guy named Ed Liska. It didn’t win those local elections, but it came close. Both sides used violence against each other. DRUM led several wildcat strikes over these years. At the core of its ideology was that there were several layers of oppression against the Black working class. Sure, America generally and also Chrysler. But the UAW was also part of this oppressive structure that needed revolutionized. One DRUM member, while being escorted from the plant after being fired, stabbed a Black worker associated with UAW leadership three times before running away and escaping not only the plant but the city of Detroit. Meanwhile, Local 3 leadership funneled money to the Detroit police to beat up DRUM activists for pay. The whole situation was very ugly.

Of course it didn’t last very long. By 1972, it was mostly dust. Some of the members wanted to keep fighting within the auto factories. Others thought they could create a national organization of radicalized Black workers. Baker was part of the latter. He paid for his activism. He was blacklisted by the auto industry and the UAW, though eventually used a false name to return to the Ford River Rouge plant by the mid 70s. He moved the remnants of DRUM into the New Communist Movement, but we are in leftist splitter land here and while he spent the rest of his life fighting for justice, not much was accomplished. The Black Power moment passed and not much had changed for most Black auto workers.

I borrowed from Jeremy Milloy, Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Violence at Work in the North American Auto Industry, 1960-1980 to write this post.

This is the 517th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.