This Day in Labor History: May 13, 1874

On May 13, 1874, a man in New York named Charles Walker was arrested for working his dog on a cider press. This is a chance to talk about the labor history of animals!

We don’t usually think of animals when we think of labor history. That makes sense on one level, but of course animals do all sorts of work for us. I’m not so inclined to make the case that cows on feedlots are doing work per se when they are living in gross conditions so that we can eat them, but there’s an argument to be made I suppose. But even outside of that, animals do work. They used to do a lot more. Think of the farm, among other things.

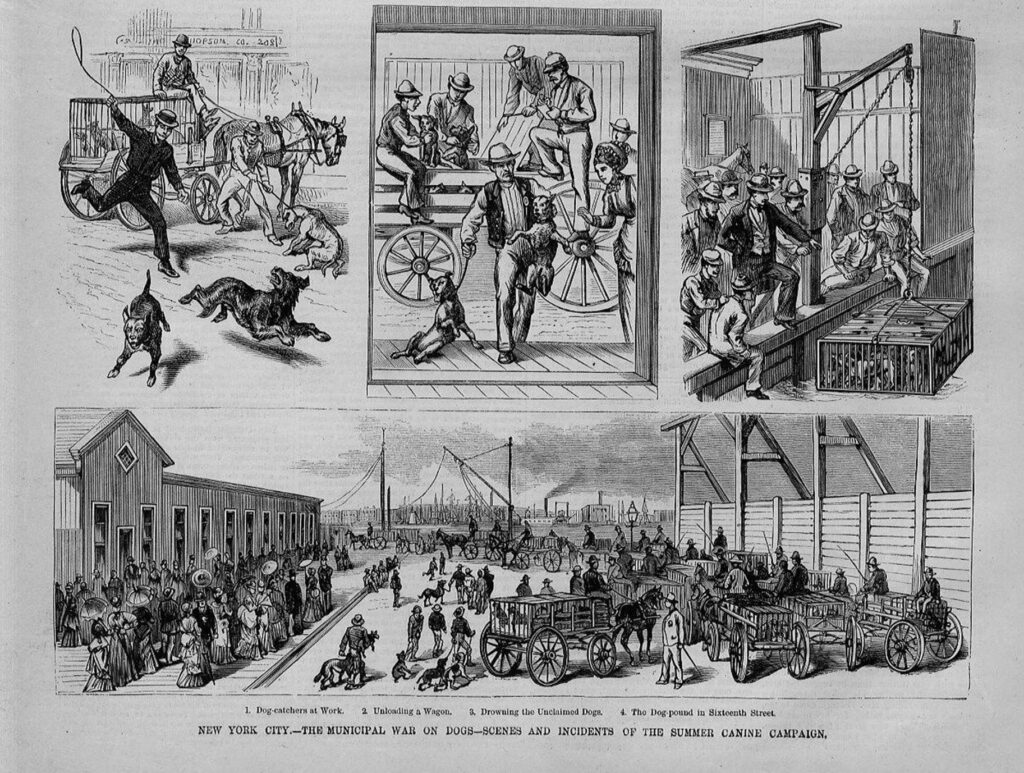

The 19th century city was filled with animals. Domesticated and semi-domesticated animals were a serious part of the city. There were horses almost everywhere and they all did work. Until the development of more sophisticated transportation options, it was either something drawn by a horse or you walked. But people found all sorts of ways to use animals for work. That included dogs. The idea of tying a dog to a cider press seems horrible and of course the guy was arrested so it seemed horrible in 1874 too, at least to some people. But it’s not like such a thing was uncommon. It’s also worth noting here that the 19th century city had other animals that weren’t working exactly, but still caused total chaos. That was especially true of pigs, which had tremendous value because they ate just about anything. You could just let them roam around too. So you had bands of semi-wild pigs raising hell in the streets, including knocking people down into the muck of the 19th century city. Oh, and those streets were filled with horse shit thanks to the thousands of working horses.

Henry Bergh had founded the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in New York. People came to him and told him of the horrible treatment of this dog that was on a treadmill, powering a cider press. The guy just had the dog doing it in the front window too, so it’s not like he was hiding it. Why would he think it would be a problem? In fact, many people complained about this before Bergh got around to dealing with this. He was always pretty ambivalent about this case actually, in part because he didn’t like dogs on a personal level. A lawyer named James Goodrich took the lead because of his own personal disgust. ASPCA worked with Goodrich to have Walker prosecuted. In 1867, New York had passed an animal cruelty law and they used it to prosecute Walker. He was found guilty and fined $25, which was about 3 weeks of work at that time, so it was a big time fine. Walker appealed and the case went all the way to the state Supreme Court.

Of course Walker was outraged. People worked their dogs all the time in these years. One thing that had changed though was the industrialization of dog labor. We were a long ways from a working sheepdog on a farm out here. As early as the 1820s, agricultural journals promoted the idea of working dogs on machines. People found all sorts of ways to use them to produce power. One guy in Troy, New York hooked his dog up to a treadmill to produce for a tiny machine that made small pieces of wood for sashes and window blinds. This got reported as far away as the UK as a great way to make money off dogs. European visitors to the U.S. noted the many machines Americans had developed to run on dog power. On farms, for example, dogs now often ran the churns that turned milk to butter. Dog labor could replace traditional women’s labor here, especially as butter production increased beyond a single woman and her daughters producing just for the household. This was super common. The naturalist John Burroughs, for example, remembered later in life the dog churn on his parents farm. By the 1840s, a group of dogs powered knitting machines in Boston. Poor people in American cities used dogs to pull their carts. That was especially true among the ragpickers, where the poor would tie a couple of dogs to the carts they also pulled to help with the weight.

The idea of the dog as pet in the modern context really came out of the Gilded Age, which is how you see the creation of the ASPCA and the modern animal rights movement. Henry Bergh became associated with it as its head and it was covered all the time in the newspapers, some in support and others making fun of the sheer idea of animal rights. In fact, Bergh himself basically hated dogs, but he found animal suffering revolting. He also found the poor revolting. A lot of this attack on dog labor masked attacks on traditions of work done by the poorest Americans. Ragpickers especially came under a lot of public scorn in these years and so attacking their use of dog labor was one way to further that aim.

The case against Charles Walker attempted to prove that dog machine labor itself was cruelty. One can easily make such an argument. People who testified said they had seen a Newfoundland under significant distress from being tied to this machine and forced to walk the treadmill, including fatigue, abrasions, and blood. Core to the prosecution’s case was John Hackett, a rich New Yorker who trained dogs. This got to the basic point–like much in the early conservation movement, animals were valuable for how they served the rich. How they served the poor needed a criminal definition. The defense argued that dog labor was outright good because it saved human labor.

The prosecution countered with classic free labor arguments–there was no consent from the dog, though their idea of consent from a human was that said person agreed to labor at whatever conditions the employer demanded in order to not starve. Don’t pretend like the people making this case cared about human workers and they sure as heck didn’t care about unions. This is the same year after all that New York elites called down holy hell on workers who dared to lobby for government employment in order to get through the Panic of 1873, which led to cops beating the living hell out of these workers at the Tompkins Square Riot. It would be interesting to track coverage of dog labor with coverage of these workers. I’d bet my entire retirement account that those who supported ending dog labor wanted the workers dead or in prison.

What really killed Walker’s defense though was the discovery that he didn’t actually use the dogs to press cider. He tied them to the press all right. But there was no cider being produced. Basically, he thought it was funny and put the treadmill and press in the window to attract other people who thought it was funny. So he was found guilty and the state Supreme Court upheld the fine.

In the aftermath, Walker had a new idea. He tied a Black kid, reported to be about 8 years old, to the treadmill and put him in the window instead. People wondered why this was OK and dog labor was not. Good question.

I found this story in Andrew Robichaud’s Animal City: The Domestication of America, published in 2019. Super fascinating book, you all should check it out.

This is the 520th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.