Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,636

This is the grave of James Montgomery Flagg.

Born in 1877 in Pelham, New York, Flagg started drawing when he was a young kid and he really got into it. He wanted to draw for the rest of his life, which is more or less what he did. I guess his parents were supportive of this because he started to send his drawings to magazines for publication when he was 12 and by the time he was 14, he had a contract with Life as a contributing artist, which is pretty bloody impressive.

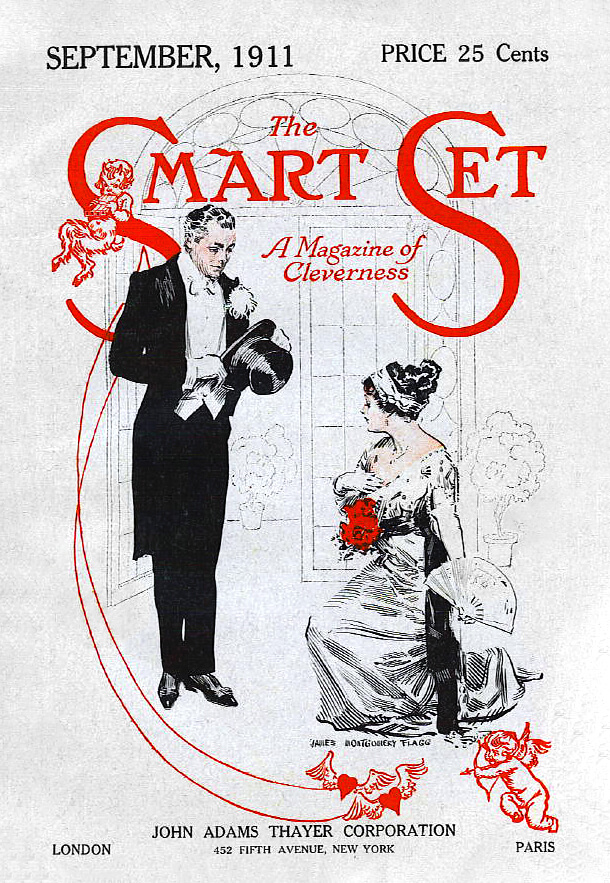

In 1894, Flagg figured he’d better study art a bit more systematically and evidently the family had money. He went to the Art Students League of New York, graduating from there in 1898. Then he went to Europe for two years to study art there, mostly in London and Paris. He came back to the U.S. in 1900 and immediately got all the work he wanted illustrating magazines and books. He had a comic strip in Judge from 1903 to 1907 called Nervy Nat. Speaking of which, remember when comic strips had an end date instead of being something that go on for generations for the few people who still really want to see what The Family Circus and B.C. are up to? He would occasionally do advertising too, but he found it slightly embarrassing, so he would only take those contracts if his name did not appear anywhere associated with the ads. Checks cashed though. William Randolph Hearst was a fan of his work and gave him all the commissions he wanted. He had a popular serial known as “The Adventures of Kitty Cobb” that he started in 1912 and it evidently ran for several years. Here’s a bit of his work from this era.

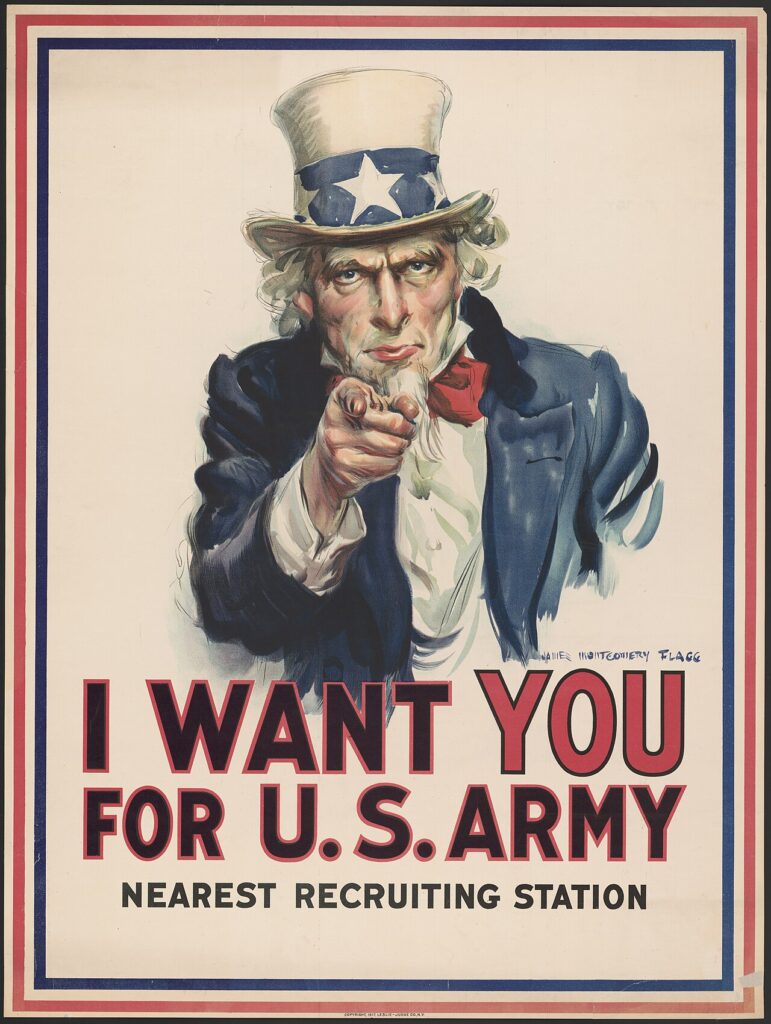

There would be no real reason to remember Flagg, except for one thing. He got involved in the U.S. propaganda effort during World War I and he drew the iconic Uncle Sam “I Want YOU for the U.S. Army” poster. Well, I can’t say that’s not iconic! What I can say, and this isn’t surprising of course, is that several years ago, I went to an exhibit of World War I propaganda posters from across the war at the MFA in Boston and I was struck how no matter the country, they were all exactly the same and used the same kind of imagery and even fonts. Still, this was a good one. You can’t deny the power of a masculine Uncle Sam pointing directly at you.

War poster with the famous phrase “I want you for U. S. Army” shows Uncle Sam pointing his finger at the viewer in order to recruit soldiers for the American Army during World War I. The printed phrase “Nearest recruiting station” has a blank space below to add the address for enlisting.

But even here, Flagg basically stole the idea from a similar British poster from 1914. That’s fine of course, the point here wasn’t to create art but to use effective propaganda to get people to enlist to fight a war. I only mention this to reinforce the international nature of this art. Flagg used his own face here as the model, but he made himself older and gave himself facial hair that he didn’t have himself. This is not the only classic World War I propaganda poster Flagg designed. Let’s take a look at a few more.

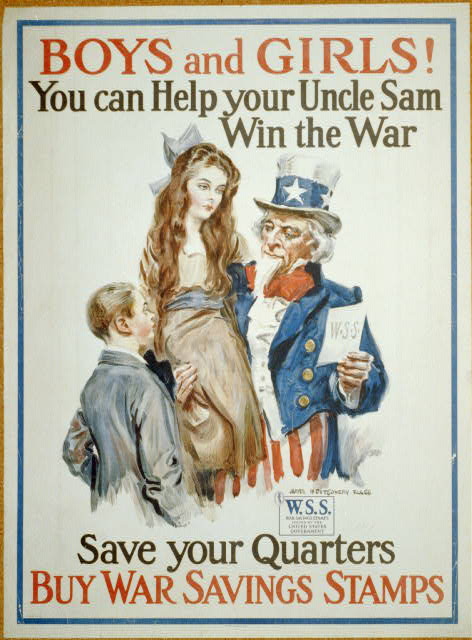

One thing that is interesting about the garden poster is that no one is more responsible for the dominance of Uncle Sam as the cartoon symbol of the United States in the 20th century than Flagg. Earlier, the visual symbol of the nation was usually Columbia, the woman portrayed above. Flagg still used that too. Of course, he is not the only one who helped with the transition–that goes back to the imperialist moment of 1898 at least. And Ford produced a bunch of cartoons for the silent movies in the war that used Uncle Sam kicking some ass. But Columbia remained a recognized female symbol that lots of Americans would have known at the time. Today? Forget about it. The students all know Uncle Sam of course (well, as much as they know anything about this country), but they have no idea who Columbia was.

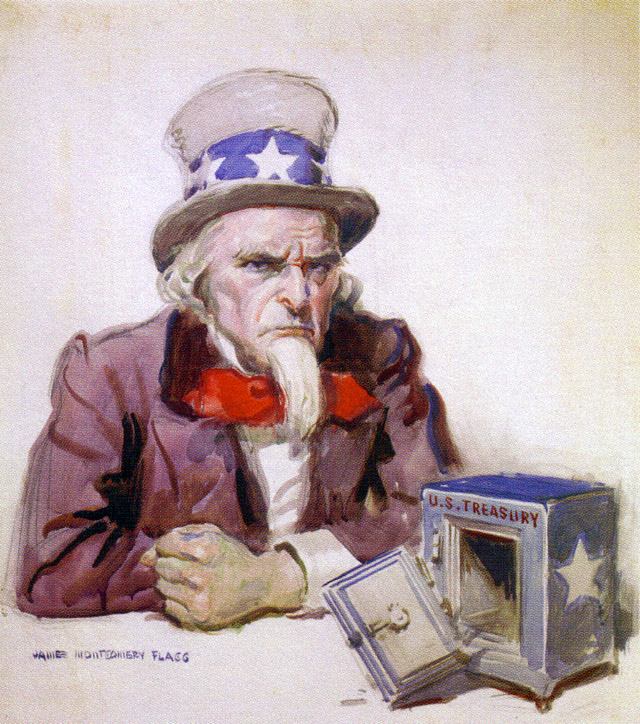

The government wanted to keep the propaganda effort up after the war too, largely to pay for the thing. So Flagg got commissions at least through 1920. Here’s another example of his work.

Personally, I find this somewhat less effective. Uncle Sam looks like a drunk who has realized he drank away all his money.

For the next thirty years, Flagg remained a leading magazine illustrator, probably the highest paid in the country for many of these years. He had the big jobs–Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s. Clearly he work anywhere he wanted. He even wrote films, including one called Perfectly Fiendish Flanagan in 1919, which evidently is a western comedy. In fact, he directed four films himself, though none seem to survive. Too bad, Pride and Pork Chops sounds like my kind of film.

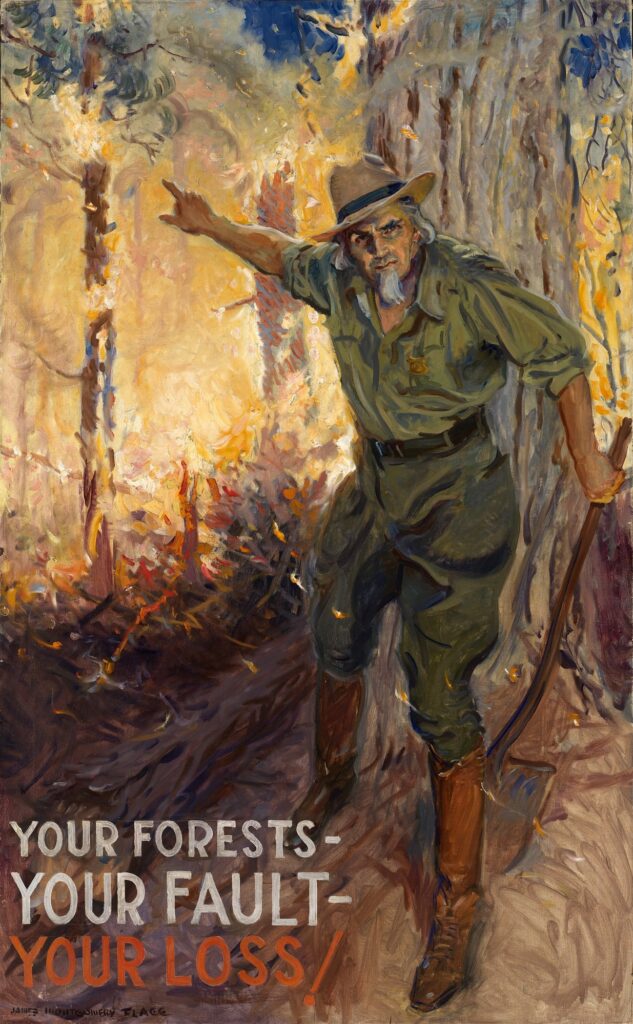

Flagg had a side gig as a portrait painter. He did this for a long time, getting in a late portrait of Mark Twain before the great writer died in 1910. His portrait of the boxer Jack Dempsey is in the National Portrait Gallery. He got rich, bought a second home in Maine, and lived a pretty good life. Here is an example of an anti-forest fire poster he made in the late 30s or perhaps early 40s.

Then World War II happened and Flagg was back with some more propaganda posters. Here is one from just before the end of war, after the Germans surrendered but before the U.S. nuked Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

But the later years of Flagg were rough. He started losing his eyesight, just about the worst possible thing for anyone, but especially an artist. By all accounts, he was a terrible patient and lashed out at all the people around him in anger, frustration, and outrage. Earlier in his life, he was known as the life of the party, a charming guy who knew everyone and got to paint those portraits because people liked him so much. Sad end.

Flagg died in 1960. He was 82 years old.

James Montgomery Flagg is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, The Bronx, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other famous American illustrators, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Howard Pyle is in Florence, Italy and if you want to send me back to Florence, I guess I can live with that sacrifice. Paolo Garretto is in Monaco, so while you are at it, I could use a cheap vacation there. Within the U.S., Lon Keller is in Annville, Pennsylvania and Philip Goodwin is in Norwich, Connecticut. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.