On Naval Power

God grant me the confidence of an economist to declaim on subjects on which they have no expertise!

Long time readers will recall the Battleship Wars, which remain the darkest period of the LGM-Crooked Timber relationship (apart from perhaps the Greenwald Conundrum and the Cooley Incident). Those battles largely ended when the commenter section of Crooked Timber basically begged John Quiggin to stop humiliating himself. John, undaunted by his previous lack of success and buoyed by a sense of… well, something… has determined to renew the confrontation, claiming that recent developments in the Black Sea, the Red Sea, and the East China Sea vindicate his claim that naval power has been worthless since 1941.

The Black Sea

John begins with the Black Sea Campaign of the Russia-Ukraine War.

Two years after the invasion, most of what’s left of the Black Sea Fleet has fled Sevastopol to take refuge in the Russian port of Novorossiysk, which is, for now, safely out of the reach of Ukrainian drones and anti-ship missiles. (As I was working on this post, Ukraine hit Sevastopol again, damaging three ships and the ship repair plant there) The Black Sea Fleet has played no significant role in the war, except as a supplier of targets and propaganda opportunities for the Ukrainian side. Its attempted blockade of Ukrainian wheat exports has been a failure.

Over the twenty-six months of the conflict, Ukrainian forces have severely attrited the Russian Black Sea Fleet, a force vastly superior to Ukraine’s rump navy, with attacks by missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles, aircraft, and unmanned surface vehicles. The most dramatic victories include the destruction of the Russian cruiser Moskva in 2022 and the submarine Rostov-on-Don in September 2023. This has resulted in damage to or destruction of some one third of the Black Sea Fleet, losses that Russia cannot replace because it cannot bring additional ships into the theater of operations (Turkey is a thing) and because it lacks local shipbuilding and repair capacity in the Black Sea littoral.

But as any good economist (or accountant, or any living human other than Donald Trump) should know, benefits must be weight against costs. If you think that the Russians have achieved nothing with the naval superiority that it still enjoys in the Black Sea, then you’re either ignorant of the situation or willfully blind. Russian naval forces have achieved nothing in this war, except…

- Seizing Snake Island, a strategic point that Ukraine was forced to retake after a lengthy, costly campaign. Had the war ended on Russia’s terms in the spring of 2022, this would have been a significant achievement.

- Fixing Ukrainian defensive forces in Odesa in the first months of war, preventing their relocation to more vulnerable parts of the front.

- Closing several Ukrainian ports, including the largest and most sophisticated container ports available to Ukraine in the Black Sea

- Severely limiting Ukrainian grain exports by forcing such exports to either use smaller, less capable and less accessible ports or to rely on vastly more expensive and politically fraught land lines of communication.

- Severely limiting Ukrainian imports (including of defense equipment) by forcing imports to use already over-burdened land-lines of communication.

- Striking Ukrainian targets directly with surface and sub-surface launched cruise missiles. These strikes in some ways replicate ALCM strikes, but complicate air defense strategy and have caused significant damage.

Apart from the Snake Island situation, these conditions continue to hold to greater or lesser degree, notwithstanding the tactical successes that Ukraine has enjoyed. This doesn’t mean that Russia has won the naval war or that Ukrainian tactical victories are meaningless. It does mean that an analyst worth his or her salt should at least try to investigate how Russia is using its military assets to achieve its war aims. It would be insane, for example, to judge the success of the Russian land and air campaigns by the attrition suffered by its land and air forces; attrition is unpleasant but generally speaking it’s an unavoidable consequence of deciding to attack a neighbor. But let’s be as clear as we possibly can be; the Russian Black Sea Fleet has, notwithstanding its dramatic setbacks, accomplished several of its most critical goals during this conflict. It has interdicted Ukrainian maritime commerce, forced Ukraine to redistribute resources and effort away from other sectors, and maintained significant pressure on the Ukrainian littoral. Attrition over the course of the war has affected its capacity to continue accomplishing those missions (although no one takes seriously at this point the possibility of a amphibious assault on Ukrainian territory) but Ukrainian trade has been substantially limited over the course of the conflict and continues to be limited today. Quiggin is, thus, wrong about his central claim. Russia is successfully leveraging its naval advantage in the Black Sea to assist its overall war effort. It may not be able to continue to do so indefinitely (and we may be close to a tipping point), but Ukraine’s inability to actually put any naval vessels to sea is devastating for its ability to secure maritime lines of commerce. Russia has been able to do so because it has submarines and surface vessels that can threaten to directly interdict maritime commerce, something that air attacks (especially air attacks at very long range) cannot hope to do with any consistency.

But we’re not done yet! As I alluded to in the recent podcast (and as I’ve argued recently in my Defense Statecraft course), the Black Sea Campaign has only limited utility for projecting the future of naval warfare. This kind of claim is often seen as a cop-out (every war is unique, etc.) but there are plenty of reasons to believe it’s especially true of this campaign. Briefly:

- Russian naval forces are incapable of using their key advantage (mobility) to fight Ukrainian air and ground forces because of the small size of the theater of operations; the Russians can’t run away and choose the timing and circumstance of their engagements because there’s just not enough water.

- Russian naval forces are suffering from unusually poor port and maintenance facilities. Sevastopol isn’t enough; it’s not for nothing that Russia’s initial invasion in February 2022 attempted to seize the Black Sea coast, including the shipyards at Mikolayiv (critical to Russian naval success since the imperial period) and the port of Odesa.

- Russian naval units are older and less sophisticated than those of just about any contemporary navy. Moreover, Russian maintenance and training are viewed by analysts and contemporaries as being somewhere between “extremely poor” and “depraved indifference to human life.”

- The Ukrainians are fighting with significant intelligence, technical, and material support from the most advanced naval powers in the world (US, France, UK).

Now, all of these should be viewed as Caveats to Lessons Learned rather than Reasons We Can’t Learn Any Lessons, because after all naval wars are incredibly rare and we have to analyze the hell out of the empirical evidence we can get our hands on. What the Ukrainians have established, beyond any doubt, is that you can over a 26 month period severely attrite an aging, unmodernized, poorly maintained naval force that lacks access to secure bases and shipyard facilities and that is incapable of being reinforced or reconstituted in any significant way. This is good and important, but it may not be replicable in any context other than the highly stylized situation that holds in the Black Sea. it would be reckless in the extreme to try to learn large lessons about the future of naval warfare from this conflict… which of course is leap that John has not hesitated to make.

The Red Sea

John argues that the two most sophisticated navies (the Royal Navy and the USN) in the world have been “humiliated” by Houthis using a combination of cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, long-range drones, and small surface craft to harass shipping in the Red Sea. Houthi attacks have certainly disrupted merchant traffic in the Red Sea, reducing overall tonnage by some 65% as shipping has diverted around the Cape of Good Hope. Many of the Houthi attacks have seen some degree of success (inflicting damage on commercial vessels) while the overall campaign has inflicted an uncertain degree of economic damage, felt most directly by Egypt which has lost out on Suez Canal transit and other port fees. The total number of ships that have been struck by some kind of projectile is in some dispute but appears to be around two dozen. The Houthis have yet to lay a finger on any Western warship, although they have forced warships to use expensive anti-aircraft missile systems (shooting down a Houthi missile or drone is often more expensive than the cost of the drone itself). It’s worth noting that the largest navy in the region belongs to the country most deeply affected by the harassment, but that for political reasons Egypt has declined to use that navy in either an offensive or a defensive manner.

I’d say the biggest difference between the Houthis and the Russians (and let’s be clear, the Houthis have failed to stop commerce in the Red Sea while the Russians have succeeded in throttling commerce in the Black Sea) is that the Russians have surface ships and submarines that can directly interdict traffic, while the Houthis are limited to taking potshots with missiles, drones, and go fast boats. Roughly 2 million metric tons of shipping goes through Suez every day, while ports suffering from the Russian blockade have exported abut 13 million metric tons of cargo in the last five months of 2023. It’s worth noting that the Houthis enjoy a vastly superior geographic position than the Russians; at various points in the Red Sea Houthis are capable of visually identifying transiting vessels (and firing on them at very short range) while Russia needs to operate at distance from bases in the eastern Black Sea under conditions of Ukrainian air superiority.

Nevertheless, the Russians effort is strategically relevant; the Houthi effort is a public relations sideshow. One area in which I definitely agree with John is that naval authorities tend to overstate the macro importance of threats to shipping lanes. Generally speaking, attacks against shipping lanes (even at choke points) divert traffic rather than stop traffic, causing temporary dislocation and a mild increase in costs. The cost advantages of sea transit over air and rail are so extreme, however, that it generally doesn’t matter if ships “take the long way around.” But that becomes rather the point when we think about the impact of naval power on maritime economics; attacks on shipping (and threats of attack) can be a big problem for specific actors (Egypt, Ukraine) without having as much effect on global maritime trade as a whole. The last thing I’ll add is that large navies have pretty much always struggled to manage attacks against shipping from small-scale naval forces. The Europeans (and later the Americans) had a profound degree of naval superiority over the Barbary states in the 18th and 19th centuries and nevertheless struggled to prevent attacks against commercial vessels.

The Indo-Pacific/South China Sea

John grants that no humiliation of naval fans has taken place thus far, because the Chinese are sensible enough to realize that the massive navy that they’ve built (for funsies, apparently) can’t actually do the job of seizing Taiwan. It is worth noting (contra John’s beliefs) that China has constructed sixteen large, modern amphibious assault vessels in the past 18 years, with (at least) an additional four big flat-decked amphibs on the way. These are supported by 47 additional landing ships that have entered service since the 1990s, to say nothing of all the other major surface vessels that China has constructed over the last two decades.

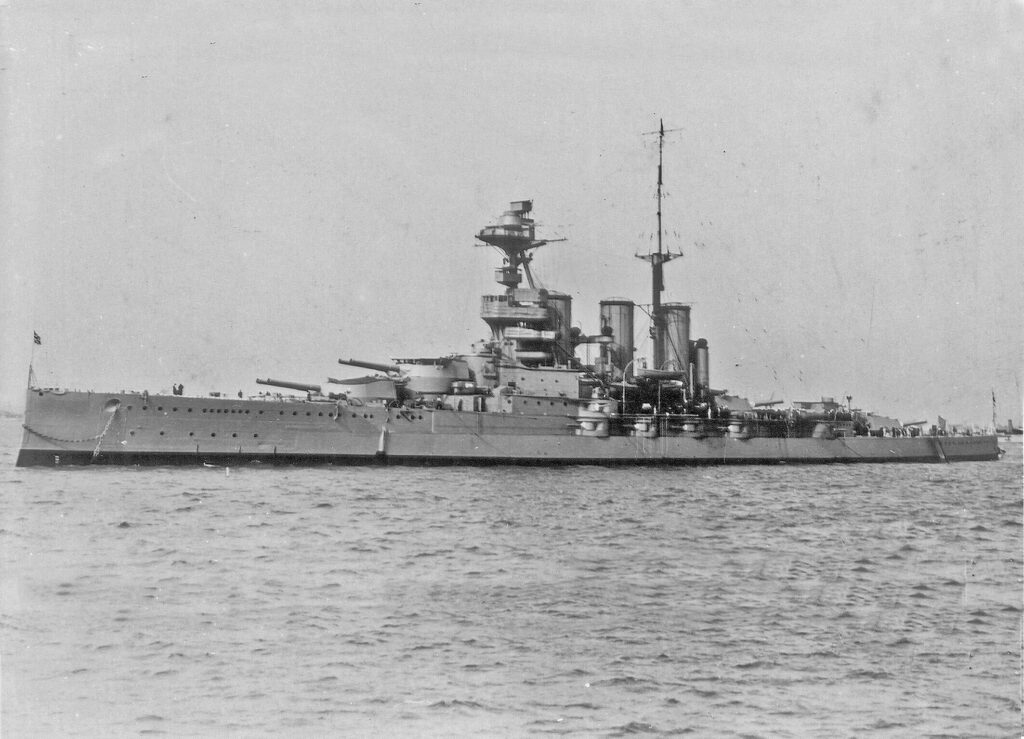

Doesn’t seem like a navy that’s afraid to think big. I doubt that the Chinese are building these ships for the aesthetics. Now, the fact that China has engaged in the largest peacetime buildup of naval capacity since Tirpitz’ naval laws isn’t proof positive that naval forces aren’t obsolete; the navies of the interwar period misallocated resources towards battleships in obvious and consequential ways, and rapidly altered their behavior in the face of evidence as soon as the fighting began. But it’s certainly worth pondering that the People’s Republic of China, which has invested immensely in cutting edge technology designed to destroy enemy naval vessels at great range, has also invested mightily in naval forces clearly designed to conduct littoral, blue water, and amphibious operations in its near and far abroad. Just because the Chinese believe in naval power doesn’t mean you have to, but you ought at the very least to take into account that China absolutely, positively, without a shadow of a doubt believes that large, modern warships are necessary to accomplish its national security ends.

John barely even considers what most observers think is rather obvious; to the extent that China is deterred from seizing Taiwan (and I don’t want to get into whether China is actually being deterred or just doesn’t want to invade; I’m inclined towards the latter but it’s awfully hard to say.), the existing naval forces of the United States, Japan, and the Republic of China constitute important elements of that deterrent. Again, the Chinese are behaving as if large numbers of additional surface warships will help them achieve their goals, which makes me think that it’s at least possible they take seriously the existing naval capabilities of their likely opponents in a naval conflict.

Wrap

Finally, a bit on the “naval fan” comments made by Dr. Quiggin. Across this entire experience, John has made clear that he does not believe that anyone who studies naval power (or the interaction between naval power and other forms of defense statecraft) ought to be taken seriously. A curious scholar might, after all, examine the voluminous work on naval theory and practice available through a wide variety of professional journals and magazines. The destruction of Force Z off the coast of Malaya, for example, is not actually understudied; there’s an extensive literature about how it happened, why it happened, and what lessons about technology and practice that could be drawn from the events. I do applaud the spirit that animates John’s interest in naval affairs, because I dislike academic gatekeeping. There’s nothing I hate more about contemporary academia than the “I’m not really an expert on that” problem. Modern academics are so paranoid about stepping on the toes of others that they’re reluctant to make any claim on anything that lays within even the borderlands of their expertise; “I’m a scholar of the French Revolutionary Army 1793-1796, inclusive; I really couldn’t comment on the events of 1798.” Moreover, as the citizen of a more or less healthy democracy he is absolutely entitled to have strong opinions and to be forthcoming about those opinions. However, it would be incredibly helpful (not to mention courteous!) if he actually bothered to learn anything about the subject that he’s trying so hard to write about.

I have spoken.