Impact fees

I don’t know if this is an important enough supreme court decision to trigger commentary from Paul or Scott, but a decision of some interest to those of us who follow housing and land use policy came down today. In Sheetz v County of El Dorado, the Supreme court unanimously ruled that:

developers and home builders in California may challenge the fees commonly imposed by cities and counties to pay for new roads, schools, sewers and other public improvements.

The justices said these “impact fees” may be unconstitutional if builders and developers are forced to pay an unfair share of the cost of public projects.

California state courts had blocked such claims when they arose from “a development impact fee imposed pursuant to a legislatively authorized fee program” that applies to new development in a city or county.

But the 9-0 Supreme Court decision opened the door for such challenges.

The decision could have wide impact in California, since local governments have increasingly relied on impact fees rather than property taxes to pay for new projects.

But the justices did not set a rule for deciding when these fees become unfair and unconstitutional.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson said they joined the court’s opinion in Sheetz vs. El Dorado County because it was limited to allowing such challenges.

A few thoughts:

- To state the obvious, there are good reasons to be wary of a conservative court expanding the scope and application of the takings clause, and that obviously applies here.

- The fact that the decision is 9-0 serves to ameliorate some of those worries, at least for me. Louis Mirante has a worth-reading thread on twitter in which he speculates Jackson and Sotomayor’s price for joining the majority was preventing Thomas from writing the controlling decision (it was Barrett) which could have been much more radical and eliminated impact fees altogether. As Mirante put it “everyone knew the conservatives were going to cook fees, the question was how hard.”

- I haven’t read the decision carefully but based on the above story and other write-ups I’ve seen, this definitely seems like a major shift in power to the judiciary. “Unfair share” is, to put it mildly, a highly constestable standard.

- Most knowledgeable observers seem to think this will end up reducing impact fees pretty substantially. One thing I’m curious to see is if a relatively consistent judicial standard for judging impact fees will emerge fairly quickly, or if we’ll have a wild-west period where different judges will use radically different standards to assess the unfairness of current impact fee rates around the state.

- On the merits of the underlying policy issue, I think there are basically two stories to be told about impact fees in California, and neither of them make this particular policy instrument look particularly good.

- One of them is the NIMBY story. The more you can make the construction of new housing cost, the less of it you’ll get, which is in itself a victory for NIMBYs. Furthermore, a key NIMBY narrative is that new housing “does nothing to improve affordability because it’s really expensive and only an option for the rich.” This is wrong as an empirical matter (filtering is real) but it is also something NIMBYs in markets like California decry and underwrite at the same time–by piling additional costs on housing construction, you not only ensure you’ll get less of it, you’ll ensure that what you do get is as expensive as possible, making your critique of market rate housing seem accurate. When extremely wealthy municipalities like Sunnyvale impose six figure fees on new homes, you don’t have to be that cynical to figure out what’s going on.

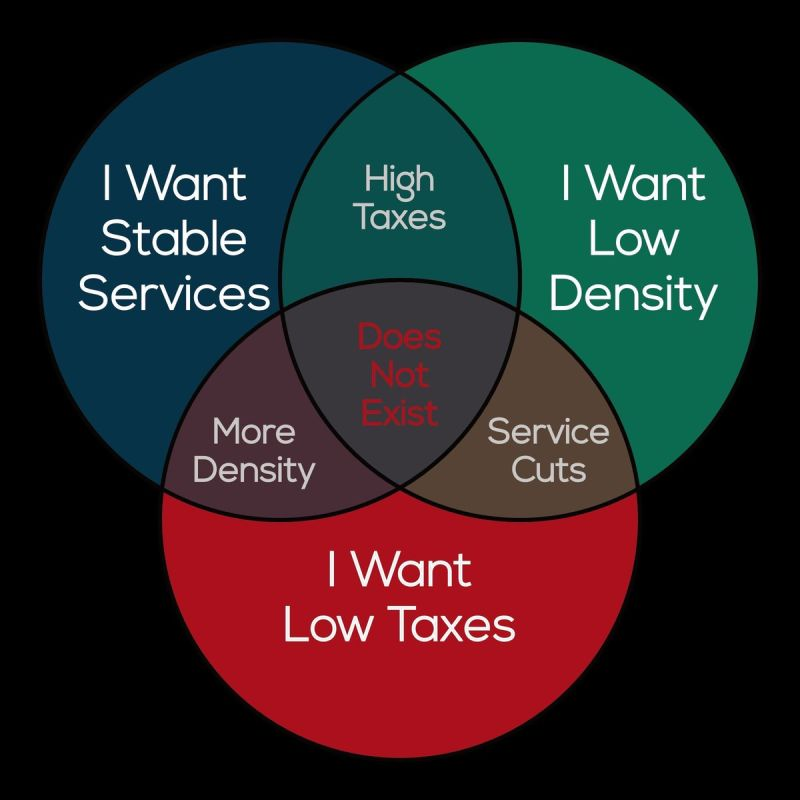

- The NIMBY story, of course, isn’t the only story. Even moderately pro-housing politicians often support impact fees. In an important sense, impact fees enable politicians and incumbent residents/voters to lie to themselves and each other about the amount of tax revenue needed to maintain infrastructure and services over the long term. I once had an extended back-and-forth on twitter with a former member of the city council in Seattle–a left-leaning CM who had views on most issues, including housing and land use, that I thought were pretty sound, for an electable politician, but who was pro-impact fee (Seattle doesn’t have them, he was trying to get them introduced on his way out the door, unsuccessfully). The basic logic of the standard justification for impact fees is that they are needed to address infrastructure improvements to accommodate that new development. That suggests something is fundamentally wrong with the current tax structure. Compare two timelines: in timeline A, a city isn’t growing and there is no new development, so no impact fees are collected. Presumably, that means the general taxes collected to cover infrastructure, which remain steady since there has been no change in the tax base. In timeline B, the city grows (in population and general tax revenue) by 20%, thanks to sufficient new development to make room for the new residents. In a no-impact fee environment, there’s 20% more revenue and 20% more residents to serve. If there are any efficiencies of scale at all, that should put the city in a better position. The idea that tax rate X provides sufficient infrastructure for 500k people, but not for 600k people, requires one to assume that greater density does the opposite of what we know it does for the cost of public services. What’s really going on here, of course, is that voters and the politicians who represent them are in complete denial about the trilemma captured in this post’s image, and impact fees are a way for them to retain that denialism at the expense of new residents (while pretending it’s those straight-out-of-central-casting mustache twirling villains we call “developers”, rather than than normal people with bad timing, who’ll pay the costs.

- In California the elephant in the room is of course Prop 13, which has rendered using the most logical tax source for local infrastructure incapable of generating sufficient revenue. Even if local voters and politicians decided they wanted to get serious and be grown-ups about this issue (they don’t of course) they’d be functionally unable to do so due to state law. So for California, at least, the contradictions inherent in their tax code and underlying approach to governance may be about to heighten.