Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,566

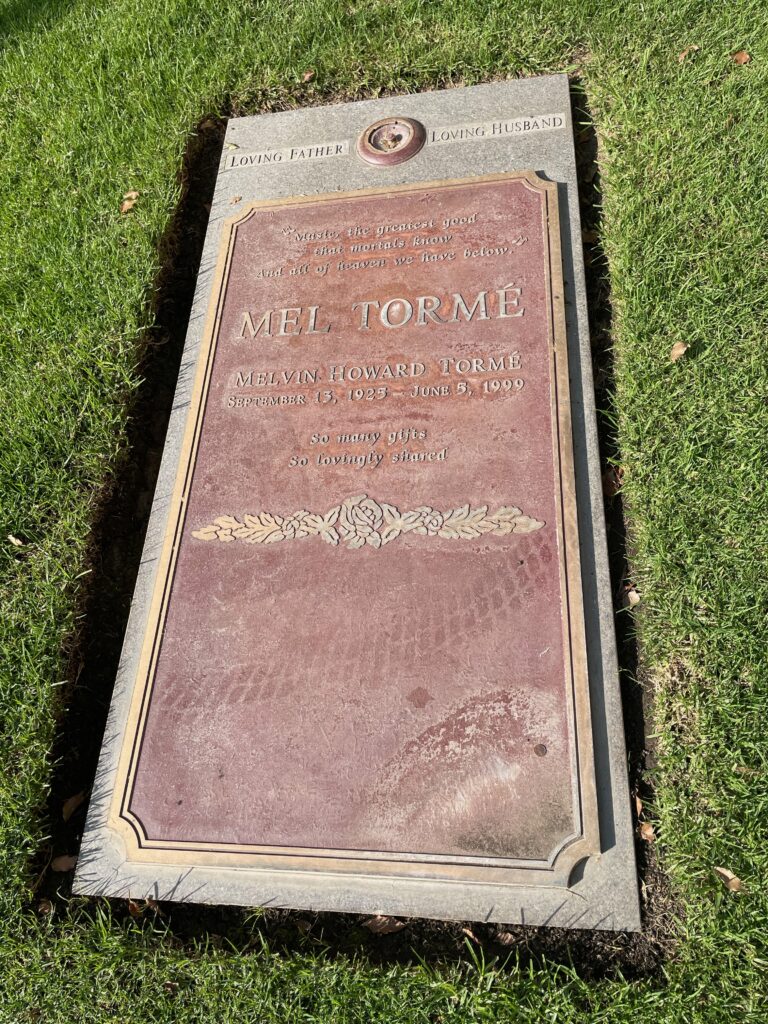

This is the grave of Mel Tormé.

Born in Chicago in 1925, Tormé grew up in a Jewish immigrant family, at least on his father’ side, who had come over from Poland. His mother was born in New York. From the time he was a tiny toddler, he was seen as a great singer. He sang at the age of only 4 with the Coon-Sanders Orchestra, which was a prominent Kansas City band named after its co-leaders, while it was playing Chicago. He went to school and graduated high school and all that, but he was performing his whole life. By the time he was 8, he was doing radio plays in Chicago. He started writing songs too, at the age of 13. By the time he was 16, he wrote a hit song called “Lament to Love” for Harry James.

So Tormé was almost destined for the big time. Chico Marx started his own band in 1942 and hired Tormé to play drums and do some singing. In 1943, he was cast in Frank Sinatra’s first film, Higher and Higher, an adaptation of a popular Broadway play of the early 40s. By 1944, Tormé formed his own group, Mel Tormé and the Mel-Tones and they started having hits pretty quickly. There was a brief pause due to Tormé needing to serve in World War II, which he did near the end of the war before a 1946 discharge.

By 1947, Tormé had hit the big time. He starred in the film Good News with Peter Lawford and June Allyson and his role turned him into a teen idol. The Velvet Fog legend was born through a bunch of top hits. The Copacabana disc jockey Fred Robbins gave him the name, though Tormé himself absolutely despised it. Now, Tormé ever only had one #1 hit, with “Careless Hands” in 1949. But for the next few years, he was consistently near the top of the charts with his version of contemporary pop with jazz and classical influences. He is considered one of the people who brought cool jazz to the mainstream, which I must say is far from my favorite era in the genre. But Tormé was absolutely a skilled arranger and singer with a great sense of timing.

By the late 50s, culture was changing rapidly and Tormé’s popularity declined. He was still a big deal, but to an increasingly older crowd and, later, to an era nostalgic for the 50s. But he did pretty OK. He had some acting gigs, including a co-starring role in Dan Raven, with Don Dubbins, which was a crime show. He was in a western with Jack Lord called Walk Like a Dragon. Incidentally, Tormé actually was a guy who liked old westerns and the guns in them and could legitimately draw very quickly. Should have put him against Eastwood.

Tormé still managed some minor hits in the 60s too, one of which reached #4 in the UK. He did have respect from other musicians and singers, which helped him when the albums weren’t really selling. He was hired by The Judy Garland Show to write songs and arrangements. But Garland and him didn’t get along so she canned him. He had his revenge though. Shortly after she died, in 1970, he published his first memoir of his work–The Other Side of the Rainbow with Judy Garland on the Dawn Patrol. It was 100% a revenge hit piece against someone he really hated.

Tormé had something of a comeback starting in the late 70s, with the rise of nostalgia for the 50s. Part of that was a return to respecting his style of vocal jazz. Part of it was just that era’s desire to relive “simpler times,” whatever that was supposed to mean. But whatever, good for Tormé. He became an institution. He was super popular in Europe, which didn’t hurt. He also had a long-standing gig in New York, at Michael’s Pub on the Upper East Side. Overall, he was performing about 200 times a year in this period, which is pretty impressive. He performed with Was (Not Was) on “Zaz Turned Blue,” a song about erotic asphyxiation, so I guess Tormé had a sense of humor too.

Where I remember Tormé entering my life–and I suspect a lot of you Gen Xers are in the same boat–was Harry Anderson promoting him all the time on Night Court. That was such a weird show looking back at it (I haven’t seen the reboot) in a number of ways. One of them was definitely Anderson having the space to engage in his passions and Tormé was definitely one of those passions. He even appeared on the show a few times. And in fact, Tormé liked to work a lot, so he was on a lot of TV over the years, everything from playing himself in an episode of Seinfeld to doing voice-over work and pitching on commercials. He was making money and who can blame a singer for doing that?

In his later years, Tormé kept working. He recorded a number of albums in the 90s. I haven’t heard any of them and I doubt I will ever do so, but for fans of his, at least he was providing some fresh material. He also wrote a biography of his friend, the drummer Buddy Rich, published in 1991. Actually, Tormé was a pretty good drummer too. He got the sticks out to play with Benny Goodman at the 1979 Chicago Jazz Festival, though I think Tormé himself would admit that he was not the equivalent of Rich or his personal hero, Gene Krupa. Also, Tormé wrote quite a few books. He had his hate book about Judy Garland of course, but also a song reflecting on singing popular music, a memoir, and even a novel.

In 1996, Tormé suffered a stroke and never really recovered. He died in 1999. He was 73 years old. At Tormé’s funeral, Harry Anderson gave the eulogy.

Let’s watch some Mel Tormé.

Mel Tormé is buried in Westwood Memorial Park, Los Angeles, California.

If you would like this series to visit other singers of the crooner age, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Frank Sinatra is in Palm Springs, California and Nat King Cole is in Glendale, California. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.