Has California’s housing policy revolution been successful? Will it be?

In the last decade or so, the status quo of near-total deference to local governments on housing and land use policy, leading to exclusionary policies that create economy and middle class-crushing housing shortages, placing the cost of home ownership and leases in many desirable locations out of reach for much of the middle (and sometimes upper-middle) class while promoting climate destroying sprawl, has started to erode. This erosion crosses partisan divides, as major state-level land use reforms have passed in blue states like Washington, Oregon and Vermont, but also red states, perhaps most notably Montana, but also Florida, Texas, and others. But nowhere has state-level housing reforms generated as much activity, and as much legislation (and the rediscovery of long-underutilized state powers from a previous generation’s housing policies) than in California, which is ground zero of the housing policy revolution.

This string of recent legislative and political success has inevitably produced some “what does it all mean” reflections. One genre of such reflections takes the housing policy revolution in California to be something of a failure. The basis for this is simple enough: new housing construction has remained basically flat since the mid-teens throughout the era these policy reforms have been passed. Christian Britschgi provides a good example of this genre, accounting for the lack of progress (outside of ADUs, where he rightly acknowledges the policy changes have been unambiguously successful) thusly:

So, what’s going on? Why haven’t other YIMBY housing laws kicked off a boom in new duplexes and transit-adjacent apartments as they have with ADUs?

I’d boil it down to two basic problems. Firstly, many YIMBY reforms have focused on handing down better bureaucratic mandates to local governments who have no interest in reforming their own housing laws. Secondly, the Legislature lards down what could be productive housing laws with endless interest group carveouts and handouts.

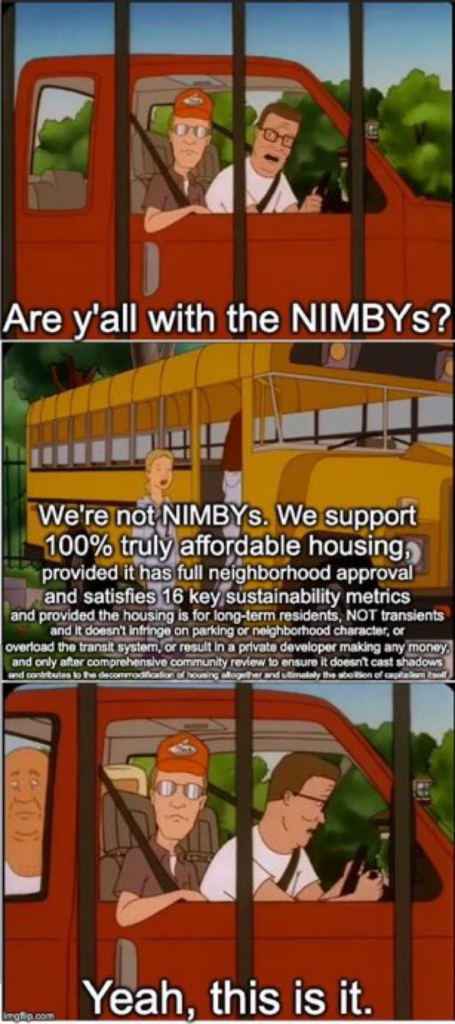

Both of these points are more or less sound; the resistance and foot-dragging from local government on the legal mandate to reform their own laws and procedures has definitely slowed down reforms, and watering down reforms and/or payoffs for local interests have sometimes been the price of winning over the median vote. Nevertheless, I’m a bit more optimistic than Britschgi. I’ve been having a hard time putting my finger on exactly why I react to the current moment with more optimism, and a couple of recent housing stories helped me figure it out. They come from two of the most recalcitrant, reactionary faux-left NIMBY consensus cities left in the state –a consensus which has faded considerably across most of the state and especially in Sacramento (not just the legislature, but the city government too), still clings to power, on the city councils, the ecosystem of politically connected non-profits, and deep in the cities’ own administrative departments: San Francisco and Los Angeles.

The story from San Francisco is at first glance a minor one. A proposal to build a zoning-compliant 24 unit building on a current parking lot (along with an adaptive re-use of an old building that used to be a private library for a now-defunct medical college) in the wealthy-even-by-San-Francisco neighborhood of Pacific Heights, was approved by the SF board of supervisors by a 10-1 vote. In approving it, they rejected an appeal by a neighborhood NIMBY group “Telegraph Hill Dwellers,” who were pushing for the city to require a full project-specific environmental impact study.

Opponents argued that the project required a full environmental impact report because of its potential impact on the library building, known as the Health Sciences Library, a San Francisco landmark built in 1912. They argued that the Planning Department had wrongly determined that the project could piggyback on a broader, citywide environmental study that was part of the city’s general plan.

……

Attorney Richard Drury, who represented the appellants, argued that the environmental study completed as part of a broader general plan didn’t specifically analyze the impact the project would have on the historic library. While San Francisco regularly allows proposed developments to bypass full environmental studies because they are located within the boundaries of specific neighborhood plans — think Rincon Hill, Market-Octavia, or Central SoMa — there is no specific area plan that covers the Sacramento Street property.

“If this were to be allowed, no residential project would ever have to do project level (environmental review) in the city of San Francisco ever again,” Drury said. “And that is just not right.”

Telegraph Hill Dwellers President Stan Hayes said the project would set “a sweeping precedent” that would result in “opening the floodgates to future projects” that “sidestep CEQA.

Some background on this: One interesting thing we’ve learned about San Francisco, as state housing law has put pressure on the NIMBY consensus, is that they’re actually less committed to maintaining current zoning than they are to their precious process. An older state housing law, revived and given real bite by current AG Rob Bonta, required San Francisco to submit a complaint “housing element”–that is, a plan to change zoning and other regulations to meet their 8 year housing target for the RHNA (regional housing needs allocation) cycle. For decades these plans were openly unserious; cities could submit obvious nonsense and no one would complain. Now, the process is being taken more seriously, and there’s a penalty for not having a housing plan deemed in compliance by the relevant Sacramento bureaucrats. If you fall out of compliance, your city is subject to what’s become known as the “builder’s remedy”–essentially, you have to approve any new housing, regardless of zoning, proposed by a developer, as long as 20% of units are set aside as affordable housing. This penalty specifically targets wealthier areas–in areas where home prices aren’t very high, that level of affordability set-asides would render most projects non-profitable–but of course that describes pretty much all of San Francisco. Also new for this RHNA cycle: the state isn’t just demanding cities come up with a serious plan, they are monitoring the cities to make sure they actually follow through. The Department of Housing and Community Development (the state bureaucracy that oversees this process) and San Francisco had some terse back-and-forths over the last year about their progress on the plan (then deemed compliant) they submitted about a year ago, which includes both upzoning and procedural reforms) to remove some of the myriad barriers to housing approval. A large portion of those 10 yes votes on this project likely would have been no’s, but for the sword of Damocles that is the builder’s remedy. Another important contributor to this story is a 2023 housing bill proposed by San Francisco’s own Phil Ting: AB 1633, which creates paths to impose a number of potential penalties on municipalities that abuse CEQA to block housing. (UC-Davis Law Professor Chris Elmendorf, a must-follow for those interested in the in-the-weeds details of California Housing Law, explained why he thinks 1633 will be a particularly high impact piece of housing legislation in this thread.)

The impact of this change to the incentive structure won’t just be limited to faster approval and less denials. Some unknown number of potentially viable zoning-compliant projects in San Francisco never get off the ground because of the lengthy delays, studies, and uncertainty the San Francisco way of doing things injected into the process. Confidence a project can pass a CEQA review on the merits isn’t enough–you have to have the capital to fight through it, paying taxes and other expenses for years, on top of construction costs. (And of course the notion that “the environment” is best served by requiring each and every infill housing project to undergo a lengthy, costly review is too silly to take seriously, which is why it’s almost never defended on the merits; NIMBY defenses of this kind of CEQA abuse treat it as a community defense tool against unwanted development.) If the effects of the HCD taking the housing element process seriously+AB 1633 change the pattern, perhaps fewer new housing developments will be dead before they even reach the proposal stage.

That hunch–“if we reduce uncertainty and pointless unnecessary process costs and delays, more housing at a wider range of price points will be built”–is also in evidence in what is arguably a more important story out of Los Angeles. Here, the story starts not with state law, but with an executive order from Mayor Karen Bass. But a host of state laws are conditioning and boosting the impact of that order. Ben Christopher at Calmatters has the story, which I’d encourage interested parties to read in full:

The seven-story apartment building planned for West Court Street on the south side of Los Angeles’s Echo Park neighborhood doesn’t make sense, not if you know anything about affordable housing in California.

All 190 of the proposed units will be reserved for people making under $100,000, which in Los Angeles makes this an “affordable housing” project.

But unlike the vast majority of affordable developments that have been proposed in California in recent memory, no taxpayer dollars are allotted to build the thing. Especially in the state’s expensive coastal cities, the term “unsubsidized 100% affordable project” is an oxymoron, but Los Angeles is now approving them by the hundreds.

That’s thanks to an executive order Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, signed in December 2022, shortly after being sworn into office. In the year and change since, the city’s planning department has received plans for more than 16,150 affordable units, according to filings gathered by the real estate data company, ATC Research, and analyzed by CalMatters. That’s more than the total number of approved affordable units in Los Angeles in 2020, 2021 and 2022 combined.

…

Between the extraordinary cost of building new apartment buildings in coastal California and the money that a developer can recoup through legally capped rents, traditional affordable housing projects almost inevitably run a sizable financing gap. That gap is almost always filled by public subsidy. A large project might require half a dozen loans, grants and tax bill write-offs from local, state and federal housing agencies. Most of these sources of public finance come with strings attached, which can saddle projects with yet higher costs and further delays.

Los Angeles’ new breed of affordable housing circumvents all of that — at least on paper. None of these units have actually been built yet. But talk to supportive policy advocates and industry players in Los Angeles and you quickly run out of new synonyms for “unprecedented.”

“This is clearly a monumental shift in how affordable housing is developed in the state,” said Mahdi Manji, policy director at Inner City Law Center, a legal service provider and affordable housing advocacy group in Los Angeles’ Skid Row. “We just haven’t seen this before.”

Privately funded developers hoping to crack Los Angeles’ affordable housing market tend to follow a familiar pattern.

First, they evoke Bass’ order — “Executive Directive 1” — to guarantee and speed up the process.

The order sets a shot-clock of 60 days for the city’s planning department to approve or reject a submitted project. As long as that project meets a basic set of criteria, it must be approved. That means no city council hearings, no neighborhood outreach meetings and no environmental impact studies required.

It also means less time getting a project green-lit.

“To go from acquiring a lot to putting a shovel in the ground in less than a year is kind of unheard of,” said Steven Scheibe, a small-scale developer working on his first entirely affordable project through Executive Directive 1.

Less time spent paying off debt, making payroll and ensuring skittish investors that the project is a sure thing saves projects on the front end.

….

Most so-called “ED1 projects” also make use of a hodgepodge of statewide “density bonus” laws that allow developers of 100% affordable housing projects to pack far more units and floors onto a given lot than would otherwise be allowed under local zoning rules. These laws also let affordable developers pick and choose from a wide range of goodies and freebies that cut costs further and allow for yet denser development. That means no parking spots, limited open space, smaller rooms and fewer trees.

All those added units mean developers can set the rents lower and still pay themselves back for the cost of construction and then some.

Together the executive directive and the density bonus form a necessary “one-two punch” to make these projects work, said Charly Ligety, a director of research and development at Housing On Merit, a nonprofit that invests in affordable housing projects. “It’s, one, ‘Oh, I can put 80 units on a single family plot…’ and then, two, ‘…and I can get it approved quickly.”

One thing Christopher hints at in this story is that this may have been accidental on Bass’s part. Her mayoral campaign gave little indication she’d be pushing any limits on behalf of the housing abundance agenda; she seemed to be more of a status quo, “lip service for supply, subsidize demand a little more, call it a day” kind of politician. On this theory she may have thought her EO to give a boost to affordable housing developers would only matter to the conventional kind of affordable housing developer–politically connected and heavily subsidized. And one could hardly blame her; developers building homes the middle class can afford without subsidy, while perfectly normal for much of history and, still today, much of the country, was so utterly foreign to 21st century LA that one can be forgiven for not anticipating the possibility.

Here again, we see the cumulative effect of several different piecemeal reforms housing that might not have been particularly effective on their own, but start to get results in combination. Getting housing construction for this level affordability to pencil out without subsidy requires both various affordable housing density bonuses from state housing law, and the process reforms of Bass’s EO. This also exposes one of the most persistent left-NIMBY articles of faith: that developers will never voluntarily build affordable housing, they’ll always just chase the luxury market. This falsehood has had some real persuasive power because conditions have been created that make it appear to be true, but that truth is an artifact of malignant policy interventions. It turns out if you legalize the conditions under which new housing at middle class prices can be profitable, and those greedy bastards will build it.

As a coda to this overlong post: recent events in the CA senate race demonstrate another source of my cautious optimism is the shift in politics. A few weeks ago, Katie Porter, trying to find a viable lane to the left of Adam Schiff in the California Senate race, seized upon the housing crisis, where it seemed like Schiff was open to an attack, as he’s pretty much entirely ignored the issue. Her first foray into the issue appeared to frame the problem as an issue of lack of attention/subsidy at the national level and the old chestnut “Wall Street greed,” landed with a bit of thud. In reaction to that, her campaign has come back in the last few days she’s back with a more thorough program; two items on her trademark whiteboard 10 point plan are “skyrocket the supply of homes” and “unleash private capital to build houses.” The more detailed version of the plan calls out the excesses of local control and “oppressive rules like mandatory parking requirements.” What this looks like to me is that she still harbors some of the old “subsidy, not supply” left-NIMBY instincts, which is why she started there, but she and her staff are sufficiently competent politicians to see which way the wind is blowing and adjust their pitch accordingly. It’s getting her some positive attention from the press and the pro-housing crowd in CA, who have been largely indifferent to this race until now. I doubt it’ll be enough to catch Schiff, but a bit of a boost for her might lead to blocking Garvey from the November ballot, which would be nice.

TL, DR: the NIMBY power can’t be defeated overnight, or directly, in one fell swoop. That doesn’t mean we’re losing.