Intellectual property is theft

I mean not literally, but Louis Menand has a very interesting essay on the problematics of copyright law in particular.

Among these are:

Under current U.S. law, copyright terms are absurdly long — 70 years after the death of an individual creator, and 95 years after the publication of work for hire, like for example Mickey Mouse. Consequences of this include a tremendously strong incentive for individuals with valuable copyrights to sell them to corporations, since the corporation can extract value from the copyright for many decades after the creator is dead. Thus Bruce Springsteen, for example, just sold the rights to all his music to Sony for around a half billion dollars, meaning that “Born to Run” is almost sure to show up as the soundtrack to a zillion car commercials in the future, which is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives.

Another consequence of such long terms is that a huge amount of culture ends up in a gray zone, where as a legal matter someone owns the copyright, but as a practical matter it’s too expensive to figure out exactly who that might be. For example a large amount of early Motown music plus many midcentury film documentaries are currently unavailable in any commercial form for this reason. Other examples are plentiful.

Yet another issue is that the ability to create what technically are known as “derivative works” — as Menand points out culture is at the most basic level nothing but derivative works — is impaired in very questionable ways:

The no man’s land between acceptable borrowing and penalizable theft is therefore where most copyright wars are waged. One thing that makes borrowing legal is a finding that the use of the original material is “transformative,” but that term does not appear in any statute. It’s a judge-made standard and plainly subjective. Fair-use litigation can make your head spin, not just because the claims of infringement often seem far-fetched—where is the damage to the rights holder, exactly?—but because the outcomes are unpredictable. And unpredictability is bad for business.

The publisher of “The Wind Done Gone,” a 2001 retelling, by Alice Randall, of Margaret Mitchell’s “Gone with the Wind” from the perspective of a Black character, was sued for infringement by the owner of the Mitchell estate. The parties reached a settlement when Randall’s publisher, Houghton Mifflin, agreed to make a contribution to Morehouse College (a peculiar outcome, as though the estate of the author of “Gone with the Wind” were somehow the party that stood for improving the life chances of Black Americans). Then there’s the case of Demetrious Polychron, a Tolkien fan who was recently barred from distributing his sequel to “The Lord of the Rings,” titled “The Fellowship of the King.” Polychron had approached the Tolkien estate for permission and had been turned down, whereupon he self-published his book anyway, as the estate learned when it turned up for sale on Amazon.

In Randall’s case, Houghton Mifflin argued that the new novel represented a transformative use of Mitchell’s material because it told the story from a new perspective. It was plainly not written in the spirit of the original. In Polychron’s, the sequel was purposely faithful to the original. He called it “picture-perfect,” and it was clearly intended to be read as though Tolkien had written it himself. Polychron also brought his troubles on himself by first suing the Tolkien estate and Amazon for stealing from his book for the Amazon series “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.” The suit was deemed “frivolous and unreasonably filed,” and it invited the successful countersuit.

Polychron sounds like an idiot — suing the estate of an author who you have just ripped off is the legal equivalent of mailing yourself a letter bomb — but I kinda want to take a look at what he’s done, and I can’t, 50 years after Tolkien’s death and 70 years after the publication of his most famous work, which seems a bit perverse.

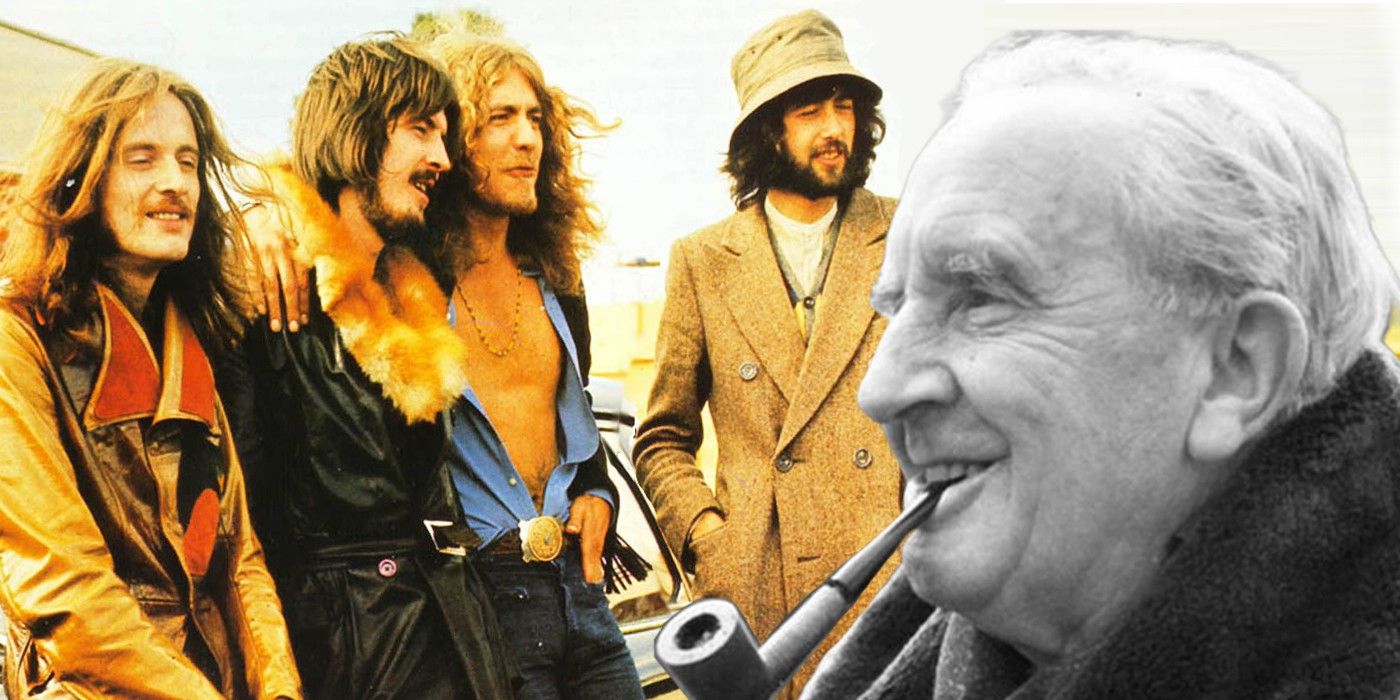

Omigod I just had a blinding insight, which is that this:

There’s a lady who’s sure

All that glitters is gold

Is lifted straight from this:

All that is gold does not glitter;

Not all those who wander are lost.

Led Zeppelin copied somebody else’s stuff without acknowledging it?

Now I don’t believe in nothing no more.

OK I realize this falls squarely into the fair use/derivative transformation space, but lots and lots of things don’t. For example the Stairway to Heaven lawsuit. And I really just did notice this at this moment, which is odd given I’m a massive fan of both the Lord of the Rings and Led Zeppelin IV. ETA: As several commenters point out, Tolkien is himself appropriating Shakespeare here — and Shakespeare’s own work is full of explicit derivation — which is Menand’s larger point about how cultural creation is always to some significant extent derivative by its very nature.

Menand is always worth reading, and here he’s talking about a very important and usually under-discussed in ordinary political and cultural discourse subject. Check it out.