Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,536

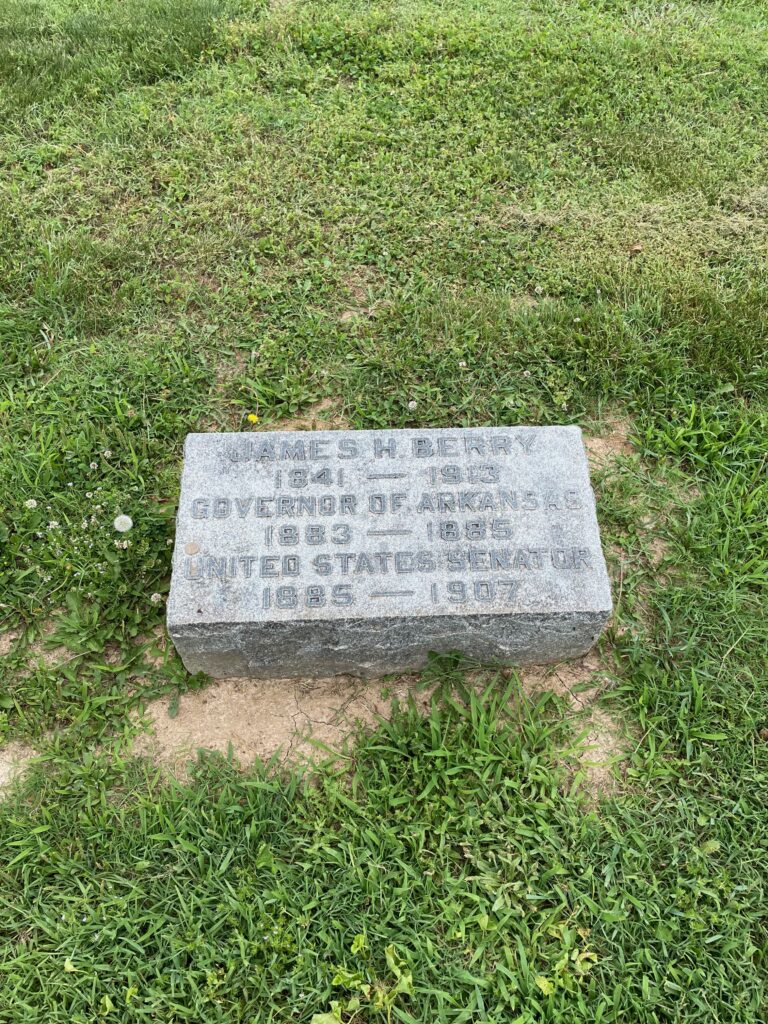

This is the grave of James Berry.

Born in Jackson County, Alabama in 1841, Berry moved to Arkansas when he was 7. His family were farmers who also opened a store when they got to Arkansas. Formal education was light for their kids. So I’m not sure whether they owned any humans or not. However, either way, it’s not at all surprising that Berry was happy to commit treason in defense of slavery. After all, even if you didn’t own slaves, that didn’t mean you didn’t want to own slaves, the sign of wealth and class in the South. He joined the Confederate Army in 1861, commissioned as a second lieutenant. They were at Pea Ridge.. He didn’t last too long. In the Battle of Corinth, in October 1862, Berry was shot in the leg and it was cut off. In other good news, the Union, under William Rosecrans, won that battle. Berry was captured by the Union army, who helped him recover from his injuries. He was then pardoned and returned to the Confederacy, where of course he could not longer fight.

Berry recovered from his amputation–no sure thing then!–and read for the law, while also teaching a bit of school. He married the daughter of a prominent businessman around this time and her father was so horrified by his prospects. he would not speak to his son in law for the next 17 years, until he became governor. Berry was admitted to the bar in 1866 and went into politics to fight against the horrors of Reconstruction, you know, Black people having civil rights and such. Berry was elected to the Arkansas legislature in 1866 as well and was there through 1874, serving as Speaker of the House in his last term. In fact, while he was there, he was one of the architects of the so-called “redemption” of Arkansas. This is the racist and horrifying term used for a long time, even by historians, to discuss the white supremacist Democrat retaking of southern states from the “horrors” of Republican rule and Black voting. His role in this was leadership in the legislative coup that kicked out the Republican speaker of the house and then calling the constitutional convention to get rid of Reconstruction. By this time, the Grant administration had basically stopped caring and did nothing.

In 1878, he became a judge on the Fourth Circuit Court. Then in 1882, he ran as governor. Of course, by this time you pretty much just needed to win the Democratic nomination to win the election and that’s what happened. His main goal was to reduce the debt, which generally meant no government services at all, and to create a state mental hospital, which I guess was one service. Berry ended up having kind of weird politics. He was a white supremacist–absolutely–but also believed in a paternalistic notion that under white leadership, Black life could get better. So he was fine with legal processes that would include the Black citizens of Arkansas. And he was horrified by lynching and even used his state power to stop a lynching once. But any actual Black political organizing or challenging white domination? Absolutely not. He also wanted to stop the convict lease system that incentivized the arrest and imprisonment of Black people to then loan out to private companies to use as free labor and work them to death if they wanted. But what he wanted was for state projects to do this instead. In any case, he didn’t succeed at getting the legislature to follow him on this anyway.

In 1885, Augustus Garland stepped down from the Senate to become Cleveland’s Attorney General. The legislature decided to send Berry to Washington. He remained in the Senate until 1907. He didn’t do much really. He was a solid Democratic vote for the Cleveland agenda, but not really much more than that. Like any good Democrat, he opposed a high tariff. He had at least slight interest in some of the Populist positions, such as the graduated income tax and some business regulations. But he was outright opposed to a lot of the reformist agenda. He was horrified by the idea of women voting. He thought the government should have no role in crazy things such as ensuring that the food we ate would not kill us, so he voted against the Pure Food and Drug Act and other such bills. Small government baby! Freedumb!! He was also an anti-imperialist, which was not uncommon at all for Democrats, as imperialism was very much a Republican policy. He opposed the annexation of Hawaii and the war in the Philippines. Now, a lot of the opposition to expansion in the Philippines had extremely racist overtones and I’d be surprised if Berry didn’t engage in this too, but the one speech I have seen from him on it really did focus on the betrayal of our own anti-colonial traditions and damning businessmen looking to profit off these poor people. So who knows.

In 1906, Berry lost his reelection race. This happened because of his opposition to one of the great reform causes of the day–the direct election of senators. A lot of state politicians were willing to give up this power to send people to the Senate and Arkansas had already instituted this. So Berry had to face a real election this time. A reformer named Jeff Davis (yep, that’s his name and he was named after that one too) beat him like a rented mule. He simply had no idea how to campaign. Time had really passed him by.

Berry was also very big into memorializing other people who committed treason in defense of slavery. In 1910, he accepted an offer from William Howard Taft to mark the graves of people from Arkansas who died in northern prisons during the war. This was a peak reconciliationist move, with northern Republicans now far more interested in remembering the Civil War as a time when good white men fought each other over causes (never mind which ones) that they believed in and fought honorably over than in remembering the Civil War as a fight for Black rights, which they preferred to not talk about anymore. In any case, Berry was very happy to serve in this way.

Berry spent his last years in the town of Bentonville, in the northwestern part of the state. He died in 1913, at the age of 71.

James Berry is in Bentonville Cemetery, Bentonville, Arkansas.

If you would like this series to visit other senators who came to Washington in the 1880s, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Daniel Voorhees is in Terre Haute, Indiana and William Maxwell Evarts is in Windsor, Vermont, although he was a senator from New York. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.