Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,534

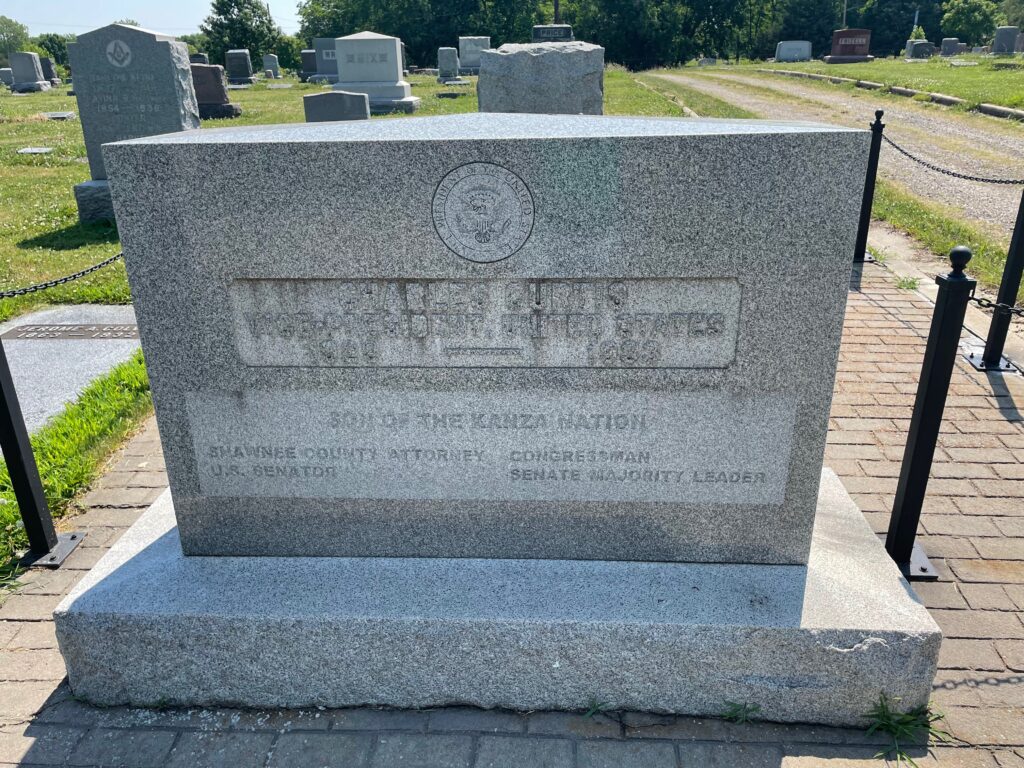

This is the grave of Charles Curtis.

Born in 1860 in North Topeka, Kansas, Curtis was a child of the mixed-race frontier. His father was European, but his mother was mostly indigenous–Kaw, Osage, Potawatomi, as well as French. What is interesting to me is how long it took me to discover that Curtis was Native. It will probably come as no surprise to you that the man was VP of the United States (Ok, maybe it will) but how did I not know that he was indigenous? The answer I think is fairly clear–the rise of identity politics made this something worth knowing but this is fairly recent. Or maybe I was just an ignorant dolt. Or both.

Anyway, Curtis’ story has some similarities to Killers of the Flower Moon, though much earlier and then again, later and weirder. Curtis’ mother died when he was a toddler and his father was in a prisoner of war camp during the latter half of the Civil War. So his maternal grandparents raised him for awhile. They made sure that his mother’s land holdings were transferred to him. The Kaw were matrilineal after all. When Curtis’ father returned from the war, he was furious that he couldn’t dispose of the land and tried to get the land, but he didn’t succeed. However, he was dropped from the Kaw’s tribal rolls in 1878, so I am not sure if his father didn’t eventually win after all.

Curtis split his later time as a child between the Kaw reservation and Topeka. He eventually decided to read for the law and was admitted to the bar in 1881. He rose pretty quickly too, which is interesting to me given his mixed race background. By 1885, he was the prosecuting attorney of Shawnee County, a position he held for the next four years. He was a Republican and this wasn’t too surprising–no Democrat was going to win in Kansas in these years. But he really did embody the Gilded Age Republican. He was elected to Congress in 1892 and served through 1906. He was known for being a good ol’boy, someone who would gladhand and have a good time and build power through personal relationships.

Now, Curtis was not going to be someone who fought for Native rights. He was a good Republican again and this meant no real room for Native rights. So he was perfectly fine with allotment after the Dawes Act. He supported the Kaw Allotment Act and gladly took his allotment too. Of course the point here was to strip land from the tribes, force them into western versions of agriculture, and give all the other land to white farmers. As historians have noted, to the extent that Curtis really had a legislative agenda, it was the destruction of the tribes and their integration into white society.

When he first got to Washington, Curtis was basically “the Indian” to everyone else. He was a bit of a curiosity. But his quite advanced backroom dealing skills made him an important player. In 1906, Joseph Burton decided not to run for reelection. Republicans in Kansas sent Curtis to the Senate to replace him. In 1912, with Democrats having taken the Kansas legislature for once, he was not sent back. But the 17th Amendment passed the next year. So he ran for a popular election in 1914 and he won. He was reelected in 1920 and again in 1926. As a gladhandler, he rose quickly in Senate leadership and became Majority Leader from 1919-24. He was known for his backroom dealing and encyclopedic knowledge of his colleagues. He almost never made a speech of any kind and was not particularly interested in legislation that would raise his profile. Rather, his profile was the dealmaker inside the Republican caucus. Curtis was also a critical player in the deal that made Warren Harding the Republican nominee in 1920, since the convention was deadlocked. As Majority Leader, he was all in Coolidgeism, cutting costs and ensuring that the government was as cheap as possible. He would occasionally feint to care about the farmers that made up the Kansas electorate, such as when he voted for the McNary–Haugen Act, which was a major goal of Henry Wallace and other progressive farmers. But when Coolidge vetoed it, Curtis was quite happy with it and defended the veto. He could go home and say he supported farmers, when in fact he basically didn’t care about them.

As you can see, Curtis was a pretty hard right conservative. There was some room for what we might see as progressive policies today–he introduced the Equal Rights Amendment to the Senate, but it would be anachronistic to say that that was a “progressive” position in the context of the time. It was easy enough to reconcile those things, not to mention that Alice Paul had horrible politics herself on most other issues of the day. As Majority Leader, he distanced himself from any indigenous affairs and when he was involved, it was to support repressive moves, such as his favoring the stripping of all new Indian land patents since 1917. The Kaw themselves found Curtis basically worthless and frequently expressed frustration with him. They wanted to open their lands to oil exploration like the Osage, but Curtis didn’t even support the federal move necessary for this. Just absolutely worthless.

In 1928, Herbert Hoover won the Republican nomination for president. He named Curtis as his VP. Again, this means that the nation has had a Native American vice-president, which almost no one has heard. Curtis and Hoover were not close at all. Curtis in fact led the anti-Hoover faction in the Republican Party. Basically, Curtis was a right-winger, even in the Republican Party. Hoover was seen as the reformer and Curtis was a Coolidge guy. But let’s be honest–what would make a better late Gilded Age Republican than being a bought off hack? So Hoover threw him the VP slot to unite the party and Curtis was happy to take the bait.

In fact, H.L. Mencken just savaged Curtis in the aftermath of this. He called Curtis “the Kansas comic character, who is half Indian and half windmill. Charlie ran against Hoover with great energy, and let fly some very embarrassing truths about him. But when the Hoover managers threw Charlie the Vice-Presidency as a solatium, he shut up instantly, and a few days later he was hymning his late bugaboo as the greatest statesman since Pericles.” Ouch.

Curtis did basically nothing as VP except annoy Hoover. It did not help when he stated shortly before the 1930 midterms that “good times are around the corner.” Yeah, that helped. Republicans were eviscerated in the 1930 election. In fact, Curtis was kicked off the ticket in 1932 for Edward Martin.

Curtis was also an early triathlete, which is some good trivia I guess. He stayed in DC after he left office and practiced the law. Since he knew everyone, it made sense. He died of a heart attack there in 1936. He was 76 years old.

Charles Curtis is buried in Topeka Cemetery, Topeka, Kansas.

If you would like this series to visit other vice-presidents, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. John Nance Garner is in Uvalde, Texas and Alben Barkley is in Paducah, Kentucky. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.