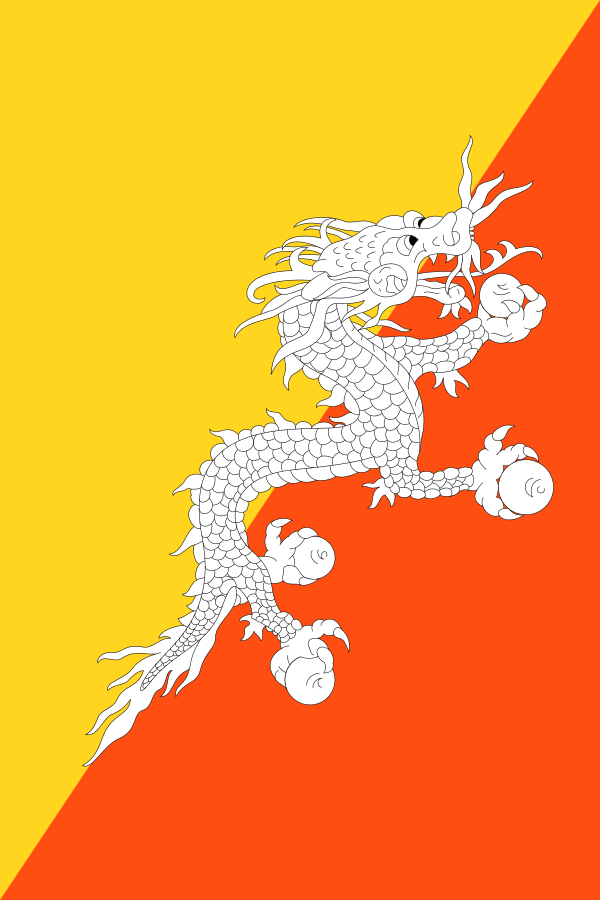

Election of the Day: Bhutan

Tuesday, voters in Bhutan will elect a new National Assembly, in the 4th election since their early 21st century democratization. When I say a “new National Assembly” I mean it unusually literally; all 47 seats will not just be new legislators, but by legislators of entirely different parties, due to their rather unique electoral system, explained below.

Much ink has been spilled on Bhutan’s democratic transition, in part because it followed an unusual path to democracy. Bhutan’s “unique transition” is fairly characterized as a “democratization by decree,” leading to a nation of “reluctant democrats.” In short: the country was quite recently an absolutist monarchy, with little movement, energy, or push for democratization. The new young King decided democratization was important to him, and his followers, presumably not wanting to disappoint him, went out and formed political parties and started doing democracy. Of course there’s a dark side to this story: The loudest voices for democracy in Bhutan in the 20th century came from the Lhotshampa community. The Lhotshampa, a predominantly Hindu community of Nepali descent, are Bhutan’s largest ethnic and religious minority. They were long a kind of second-class citizen, outsiders in their own deeply Buddhist nation. After a brief period of policies of liberalization and civil rights for the Lhotshampa in the 70’s and early 80’s, the regime started targeting them and making them unwelcome. (The first anti-Lhotshampa policy was the enforcement of a national dress code, which reflected the sartorial traditions of the Buddhist majority. From there it got much worse, leading to violence and expulsion of over 100,000 Lhotshampa in the 90’s and early 00’s. A substantial majority of Lhotshampa refugees sought and obtained asylum in the US; there’s substantial populations around the country, with Cleveland and Columbus having two of the largest, but many thousands are still stuck in refugee camps in Nepal. Despite this the lowland southern territories of Bhutan are largely populated by Lhotshampa, but they are not the politically active or demanding population they were a few decades ago. In short, brutalizing the primary national minority into submission, the argument goes, made democracy a less risky bet for the monarchy. This may help explain Bhutan’s rather unique electoral system, which seems systemically designed to make it as difficult as possible for regional parties to enter parliament (the Lhotshampa, as noted earlier, are clustered in the Southern lowlands). It would be genuinely difficult to estimate the precise balance of power between parliament and the King, since parliament is rarely directly challenged by parliament, which is comprised of politicians and parties who don’t want to do that. Of course, their electorate, by and large, doesn’t want them to do that either.

About that electoral system: Bhutan uses single member districts and a two round election. The first round of this election took place on November 30th, which I must have missed or perhaps decided to punt coverage to round 2. The first round serves two functions: First, it’s a primary, where voters can select a preferred representative from their party. But even if your party has only one candidate, you need to show up and vote, because the national vote in the first round determines which two parties advance to the runoff *in every district.* In this case the second-place party was just under 20% and only had a top-2 result in just over half the seats, but they advance in all 47 because only the top two national parties advance. (Only nationally registered parties are allowed to field candidates, and each of the five national candidates runs at least one candidate in each district). The reason the next national assembly will be entirely new is that the current ruling party, the center-left DNT came in 4th, with 13% of the vote, and the current opposition party, the center-right DPT, came in 3rd with 15% of the vote. The two parties who advanced to the national election were another center-left party, the People’s Democratic Party, who controlled parliament from 2013-2018 before being shut out, and a new party called the Bhutan Tendrel party. It seems reasonable to expect the People’s party to win big, as they recieved more than twice as many votes in round one as the nearest runner-up (43%-20%). I don’t know if this system was adopted to prevent regional parties from entering parliament, but whether that was an explicit goal or not it seems quite effective at producing that result.

What is this election about? Bhutan is really struggling post-pandemic, as its particular brand of tourism (in an effort to avoid the hippie horrors of Kathmandu in nearby Nepal, they sought a “fewer, but better, and by better we mean richer” approach, making visas difficult and requiring each traveler to spend considerable money to visit the country) has not seen a bounceback, the economy is moribund, and young people are fleeing the country in alarming numbers.

Bhutan’s youth unemployment rate stands at 29 percent, according to the World Bank, while economic growth has sputtered along at an average of 1.7 percent over the past five years.

Young citizens have left in record numbers searching for better financial and educational opportunities abroad since the last elections, with Australia as the top destination.

Around 15,000 Bhutanese were issued visas there in the 12 months to last July, according to a local news report – more than the preceding six years combined, and almost 2 percent of the kingdom’s population.

The issue of mass exodus is central for both parties contesting the poll.

Career civil servant Pema Chewang of the Bhutan Tendrel Party (BTP) said the country was losing the “cream of the nation”.

“If this trend continues, we might be confronted with a situation of empty villages and a deserted nation,” the 56-year-old added.

His opponent, former prime minister and People’s Democratic Party (PDP) chief Tshering Tobgay, 58, sounded the alarm over Bhutan’s “unprecedented economic challenges and mass exodus”.

15k Australian visas in a year is a pretty remarkable statistic for a country whose total population is roughly that of Seattle. It would be the national equivalent of 6-7 million young Americans moving to Australian in a year, which is quite a thought experiment. This kind of situation understandably leads to an anti-incumbent attitude, but after round one there are no more incumbents to punish. Bhutan is quite famous for their “gross national happiness” approach to development, which places economic growth at a somewhat lower priority than conventional development schemes. Neither party seems to be challenging that approach too directly, which is unsurprising, given how tied up with the Monarchy that approach is, and how reluctant Bhutanese politicians are to criticize their King.

The People’s party will likely dominate, given the first round results, and it’s difficult to know how to feel about that without more information about the new “Bhutan Tendrel Party”, about which my admittedly non-rigorous research has turned up very little. This brief article suggests they’re running a centrist, anti-corruption, effective public services and inclusion of minorities campaign:

The Party says its name ‘Tendrel’ symbolises a new beginning and a new era to embark on a new journey in the critical time of transformation.

BTP says the party will remain right at the centre, working towards a greater and prosperous Bhutan.

“We wanted to be very unique in terms of firstly cleansing the structural barriers. Secondly in enhancing the public services and there is a lot of scope that we can focus on in these two areas,” said Dasho Pema Chewang, the party president.

“Qualification is not the only criterion for the candidates. The experiences, dedication, accountability, and transparency are all evaluated through past records,” he said. “We do a 360-degree due diligence, not only within the committee but we also ask at the grassroots level.”

The President added that BTP will focus on inclusivity, targeting all groups including marginalized groups.

Wikipedia’s entry on the new party contains the following rather cryptic information:

Tendrel is a natural law of inter-dependence, dependent origination, or the law of cause and effect. The name also connotes auspiciousness, virtue, wellness, and harmony. Tendrel unifies and strengthens positive energy and consecrates the way ahead for a good cause. The BTP states that Tendrel heralds the beginning of a new era, a brave and prosperous new Bhutan

Huh.