Bureaucracy and its discontents

David Brooks has written a good column — and before any of you get to that, bad columnists occasionally write good columns, and good ones sometimes write bad ones; and the ability to recognize this complicating factor about the nature of reality is an essential aspect of the Liberal Imagination ™ — about the costs of over-bureaucratization:

Once you start poking around, the statistics are staggering. Over a third of all health care costs go to administration. As the health care expert David Himmelstein put it in 2020, “The average American is paying more than $2,000 a year for useless bureaucracy.” All of us who have been entangled in the medical system know why administrators are there: to wrangle over coverage for the treatments doctors think patients need.

The growth of bureaucracy costs America over $3 trillion in lost economic output every year, Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini estimated in 2016 in The Harvard Business Review. That was about 17 percent of G.D.P. According to their analysis, there is now one administrator or manager for every 4.7 employees, doing things like designing anti-harassment trainings, writing corporate mission statements, collecting data and managing “systems.”

This situation is especially grave in higher education. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology now has almost eight times as many nonfaculty employees as faculty employees. In the University of California system, the number of managers and senior professionals swelled by 60 percent between 2004 and 2014. The number of tenure-track faculty members grew by just 8 percent.

In higher ed, the proliferation of administrators is just one part of a more pervasive problem, which is the over-bureaucratization of the job itself. Imagine, for example, the time the average faculty member wastes on filling out evidently pointless surveys and annual forms, including most annoyingly such ludicrous artifacts of metastatic bureaucracy as “self-evaluations.”

And imagine the time spent reading, or at least skimming, these same useless documents, by members of various sub-committees of larger committees, conveyed to “evaluate” this “work product,” because of bureaucratic imperatives memorialized in documents churned out by other committees, higher up in the Great Chain of Administrative Being, as I believe Aristotle first noted.

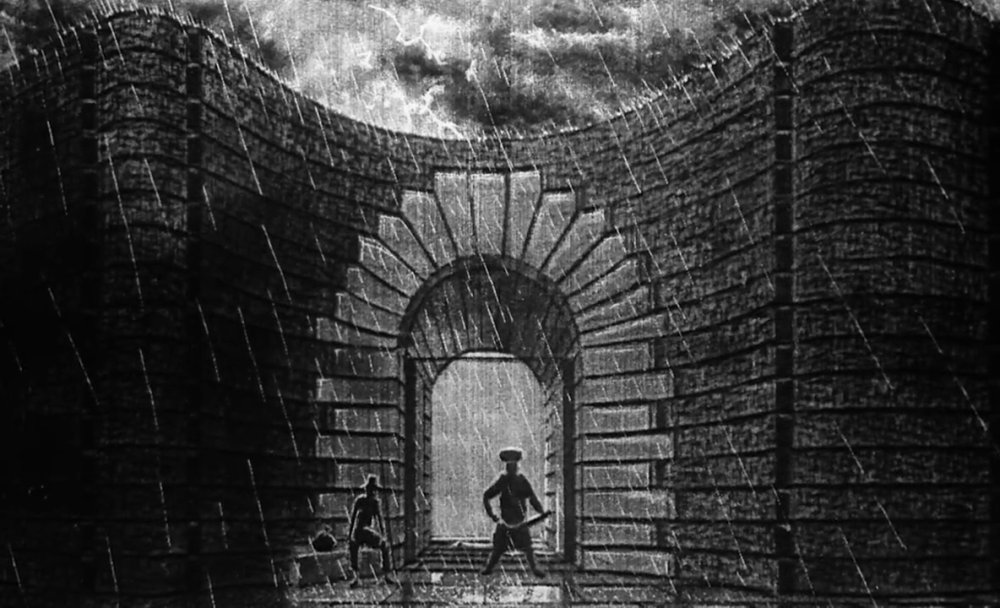

Speaking of efficient or rather inefficient causes, I’m currently enmeshed in a costly and destructive lawsuit with my employer because the following preposterous bit of bureaucratization went completely off the rails in my particular case. (I realize that hearing about the details of somebody’s lawsuit is like hearing about the details of their dreams or their fantasy football team, so I’ll try to keep this much shorter than the Kafkaesque intricacies actually call for).

About seven years ago, a good friend of mine on the University of Colorado Law School faculty noticed that The Regental Rules of the University of Colorado required every academic unit’s Annual Merit Review Process (also required under said rules) to include a “peer review component,” and that the law school’s merit review process did not include any such mandated peer review process. An expert in administrative law, he was duly appalled by this regulatory lacuna, and brought it to the attention of the Dean, etc., who after much careful study and consultation, recommended to the faculty that we vote to amend The Rules of the Law School to include such a process, which the faculty then, after much further study and consultation, duly did.

The result was an Annual Faculty Peer Review Committee, whose purpose, putatively, is to undertake a careful and considered review of the performance of every faculty member, for the purposes of making a recommendation to the Dean regarding the Merit Evaluation and Merit-Based Raise the faculty member should receive for that year.

Now this entire process is a complete waste of time, as everyone involved in it will acknowledge when they are not at that moment actively involved in performing it.

Why? Because the whole process is ridiculous on its face. For one thing, doing a serious evaluation of faculty scholarship would require the five members of the committee to actually read the publications of the 40 or so other members of the tenure track faculty produced in the year of evaluation, which they are not going to do, and in fact do not even pretend to do. (If they were to do this in a serious way, as voting faculty — hopefully — do during a tenure review of a single individual faculty member, they would do pretty much nothing else for several months).

Similarly, doing a serious evaluation of faculty teaching would require spending countless hours actually observing that teaching, since the members of the committee admit quite explicitly — it’s fascinating what you learn in civil discovery — that student course evaluations are worse than useless for this purpose: a conclusion copiously confirmed by the academic literature on that precise question.

And doing a serious evaluation of faculty members’ service would require, among other things, delving into whether the various sub-committees of various committees that faculty members served on actually did any work, or were merely nominal entities, etc., as well as investigating whether faculty members’ florid descriptions in their self-evaluations of their community service — some of these documents are positively Dickensian if not Joycean in detail, as I’ve learned thanks to the Federal Rules of Evidence — have any basis in reality, loosely defined.

Again, everyone involved in this farce will pretty much admit, under the right circumstances (gin, tonic) that the whole thing is a monumental waste of time. But here’s the thing: when they are actually doing the work — or “work” — required by the Rules, my distinguished colleagues often seem to forget this altogether. Then — such are the practically magical properties of the bureaucratic will to power — they will generate detailed Excel spreadsheets, memorializing exactly how they have gone about evaluating — or “evaluating” — their peers. (These notes sometimes document surprisingly egregious violations of federal law, but that’s a story for another venue).

As the saying goes, one should always be careful about what one pretends to be. There’s probably a rule for that, too.