This Day in Labor History: December 10, 1976

On December 10, 1976, undocumented workers in Chicago leather plants voted to unionize, leading to battle for them to have access to U.S. labor rights. Their employer soon had some of them deported for unionizing. This wound its way through the courts until the Supreme Court until, in 1984, the Court ruled in favor of the workers in Sure-Tan v. NLRB.

The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 reopened America’s borders to immigrants for the first time since 1924….sort of. It did allow people from Asia and Africa to come to the U.S. in any kind of numbers for the first time since the early 20th century. But it also placed limits on migration from Mexico, which was exempt from the 1924 Immigration Act. Although the numbers allowed from Mexico and other Latin American nations were reasonably robust under the law, it did not nearly cover the demand or the supply. Not surprisingly, undocumented migration rose. Add to that the structural changes in both the American and Mexican economies. The Border Industrialization Program of the 1960s intended to replace the Bracero Program and keep Mexican workers on their side of the border by incentivizing American companies to move south of the border. That certainly worked to attract low-capital industries such as textiles and electronics into Mexico, but it did not solve the labor problems within Mexico, which at that time partly came from a rapidly rising population. Then you had the increased globalization of agriculture. In Mexico what that meant was American investment in large farms that grew crops such as broccoli and cauliflower for the export market, as well as tomatoes and things more commonly associated with Mexico. The point here though is that both land and markets began disappearing for small Mexican farmers. As trade laws would eventually allow the widespread dumping of American corn on the Mexican market (though this did not reach its peak until after the creation of NAFTA in the 1990s), it increasingly was impossible for farmers to make a living in their villages. So they moved. Many of them crossed the border to the United States.

Employers of course wanted to hire undocumented labor. Rising standards for American workers meant that it was hard to find workers in the lowest-paid jobs, where employers resisted decent pay and conditions as hard and long as they could. There were no real consequences for employers to hire undocumented workers. Plus then you could exploit them–steal wages, terrible living and working conditions, whatever. What were they could do? Report themselves and be deported? Go for it.

Not surprisingly, this all led to a lot of legal battles. By the mid 70s, the Supreme Court was having to rule on a number of cases around undocumented workers, including their right to move on American roads, the right to attend public schools, and, yes, their right to join or form a union.

In July 1976, the Chicago Leather Workers Union started a new campaign in Chicago to organize a leather-processing company called Sure-Tan, Inc. The employer thought he had the undocumented workers in his hands. He told them not to join the union. But they were interested. In August, an employer named John Surak gathered his workers into a union and asked if they were joining the union. They denied it, very half-heartedly, and he realized there were joining the CLWU. He shouted “motherfucking sons of bitches” and stormed out of the room. If anything, this just reinforced the workers’ desire to join the union. They were sick of Surak’s intimidation and it became worth it to them to risk deportation to fight for themselves.

So on December 10, the union held the election and the workers voted in the union. After screaming at his workers, Surak called the National Labor Relations Board and reported himself for hiring undocumented workers, asking them to invalidate the election, if not deport them. Calling the government to deport your union workers became a pretty standard move by a lot of employers in industries such as leather and meatpacking for a long time after this, though I haven’t heard of a recent case of this in some time now, for whatever that is worth. But the NLRB did not do what Surak wanted. They decided quickly that their business was not in deportation or citizenship. Their business was ensuring fair union elections. So the NLRB ruled that any employee could be a member of a union, regardless of legal status.

So then Surak reported himself to the Immigration and Naturalization Service. INS was more than happy to union bust in this way. Five of his workers were soon deported. Surak was tickled pink. But the NLRB was not. They knew what this meant. If Surak got his way, then undocumented workers around the nation would be scared to form a union. So it ruled that he engaged in an unfair labor practice. The courts agreed. One of the workers, Francisco Robles, was able to return to the U.S. to testify in the case. Even the AFL-CIO actively supported these workers, and this at a time when the federation was still anti-immigration. I mean, these were the same years that Cesar Chavez was destroying his own union’s gains in the California fields by demanding that undocumented farm workers be deported. So it was by no means a given that the federation would do this. But union leaders nationally saw what this case meant for future organizing efforts.

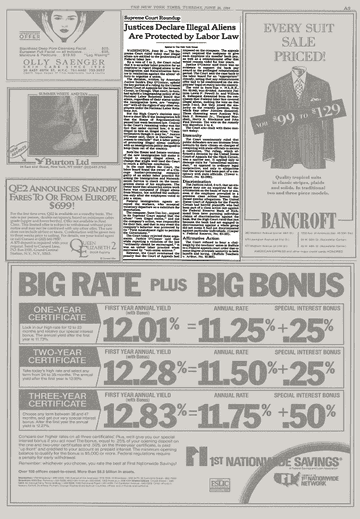

This finally reached the Supreme Court in 1984. In Sure-Tan v. NLRB, the Court ruled in favor of the migrant workers. It decided that as employees, they were under the authority of the NLRB and other domestic labor legislation. It also ruled that this decision would actually decrease undocumented migration by taking away the incentive to recruit undocumented workers, although this probably was not true. However, the Court, never being a real friend of workers, refused to actually do anything to dissuade employers from similar actions in the future. It did not rule for any kind of punishment or consequence for not following the law. The only material damage employers would face was having to pay back pay when the NLRB found a violation. This is a huge issue today too, regardless of the legal status of the workers. There’s no real incentive to not crush union organizing efforts and fire union workers. The worst thing that happens is that years later, you might have to pay some back pay to a few workers? Who cares. It’s a real problem.

In the case itself, it was 7-2 in favor of the NLRB covering these workers, with Lewis Powell and Bill Rehnquist of course dissenting because they were trash. The part of the decision that said the NLRB could not really do anything to punish employers was 5-4, with Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun, and Stevens, i.e., the good ones dissenting. In short, this was a classic O’Connor case and of course she wrote the decision.

Still, this was an important precedent for undocumented workers and as immigrants today make up a hugely important part of the union movement, the Sure-Tan case was all in all a positive in the fight for justice.

I borrowed from Ana Raquel Minian, Undocumented Lives: The Untold Story of Mexican Migration to write this post.

This is the 506th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.