People’s History of the Marvel Universe, Week 22: Anti-Mutant Prejudice and Mutant Rights In the Longue Durée

Great question!

This is a difficult question to answer, because Chris Claremont was very much of the “torture your darlings” school of comics writing, believing that the way to wring endless drama out of your characters was to keep piling tragedy on tragedy on top of them before finally giving them a moment of catharsis. This was especially true for how he handled the mutant metaphor from as far back as X-Men #99, where even when the X-Men saved the day, it would only seem to further fan the flames of anti-mutant prejudice.

That being said, Claremont didn’t present an unchanging portrait of anti-mutant prejudice constantly getting worse and worse – after all, the very beating heart of dramatic structure is variation, without which even the most grimdark tragedy becomes numbing and monotonous. So there are definitely key moments in the Claremont run where the X-Men are able to score a victory for mutantkind.

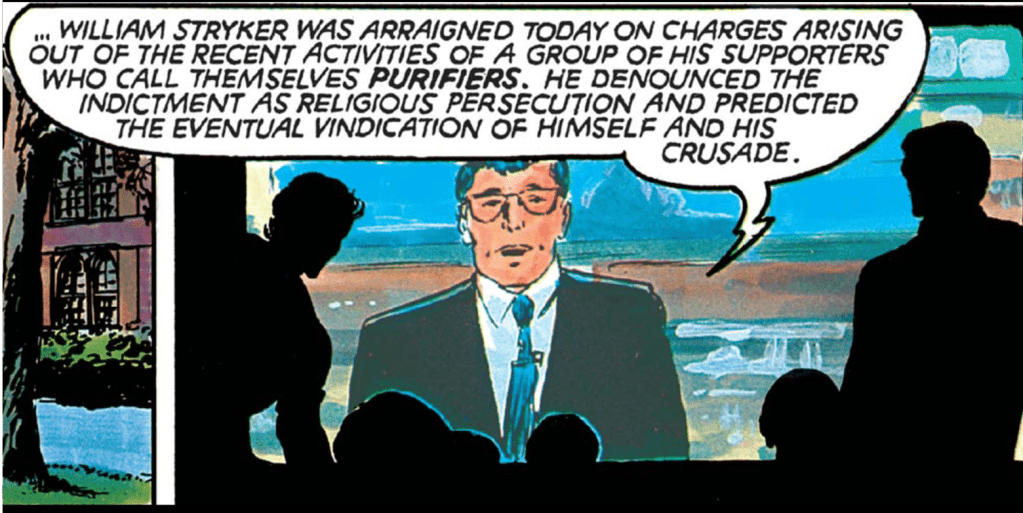

Perhaps the first and most famous instance of the mutants notching a win comes in the climax of God Loves, Man Kills – Claremont’s first great Statement Comic about bigotry. After having foiled the Reverend Stryker’s plans to exterminate mutantkind by kidnapping Charles Xavier and using a Cerebro-like device to project lethal strokes into mutant brains across the world, the X-Men confront Stryker on live T.V – again, part of Chris Claremont’s endless fascination with the power of media to shape our minds that would recur in Fall of the Mutants – fighting him on the level of ideology and rhetoric. Kitty Pryde is able to bait Stryker into attempted murder in front of the television cameras, ending his crusade of hate:

(I’ll do a full in-depth analysis of God Loves, Man Kills and how it both codifies and reveals Chris Claremont’s approach to the mutant metaphor in a future issue of PHOMU.)

The next big moment of victory I’ve already written about in PHOMU Week 20, was Fall of the Mutants. In this storyline, the X-Men face off against Freedom Force and the Registration Act and ultimately sacrifice their lives to save the world in Dallas – once again, using the power of rhetoric and media to strike back against discrimination and oppression.

After that, Claremont’s next (and arguably last) big victory for mutant rights came in the “Genoshan Saga.” (I’ll also be doing an in-depth analysis of Genosha in a future issue of PHOMU.) Beginning in UXM #235 and winding its way through Inferno and the X-Tinction Agenda, the fictional nation of Genosha was Chris Claremont’s big Statement about apartheid South Africa. An island nation off the east coast of Africa, Genosha seems to be a utopia free of poverty, crime, and disease – but its entire society rests on a foundation of mutant slavery, where mutants are press-ganged, mind-controlled, and genetically-manipulated to serve the human ruling class.

After a series of clashes between the X-Men and the Genoshan Magistrates, the X-Men defeat Genosha’s anti-mutant military and their cyborg ally Cameron Hodge. But whereas most superhero comics end with the heroes foiling the evil plan of the supervillain and restoring the status quo, this time Chris Claremont and Louise Simonson went a step beyond the norm and had the X-Men carry out a political revolution that brings lasting structural change – toppling the Genoshan government and abolishing apartheid.

Under the pen of later writers like Joe Pruett, Fabien Nicieza, and (most enduringly) Grant Morrison, the island of Genosha would be refashioned as a mutant homeland, a prosperous and advanced nation of sixteen million mutants ruled by Magneto. (Yet again, a topic for another issue of PHOMU.) Arguably ever since then, the story of the X-Men has been the story of the struggle to restore mutantkind to the position it was in before Cassandra Nova ended the first mutant nation-state, culminating in HOXPOX and the foundation of Krakoa. (A topic we’ll be covering next year when FOTHOX/ROTPOX writes the final chapter in the Krakoan Era.)