Notes on MAGA Camp

Should the blessed day ever arrive when Donald Trump is sent to federal prison, only one of his acolytes has earned the right to share his cell: George Santos, who on Friday became the sixth person in history to be expelled from the House of Representatives, more than seven months after he was first charged with crimes including fraud and money laundering. (He’s pleaded not guilty.) A clout-chasing con man obsessed with celebrity, driven into politics not by ideology but by vanity and the promise of proximity to rich marks, Santos is a pure product of Trump’s Republican Party. “At nearly every opportunity, he placed his desire for private gain above his duty to uphold the Constitution, federal law and ethical principles,” said a House Ethics Committee report about Santos released last month. He’s a true child of the MAGA movement.

That movement is multifaceted, and different politicians represent different strains: There’s the dour, conspiracy-poisoned suburban grievance of Marjorie Taylor Greene, the gun-loving rural evangelicalism of Lauren Boebert, the overt white nationalism of Paul Gosar and the frat boy sleaze of Matt Gaetz. But no one embodies Trump’s fame-obsessed sociopathic emptiness like Santos. He’s heir to Trump’s sybaritic nihilism, high-kitsch absurdity and impregnable brazenness.

Other politicians embody the sinister, cruel and disgusting aspects of Trumpism. Santos incarnates its venal and ridiculous side, the part rooted in reality TV and get-rich-quick schemes. As Mark Chiusano reports in his excellently timed new book about Santos, “The Fabulist,” if the now ex-congressman showed much interest in politics before 2016, we don’t have a record of it; his heroes were pop divas like Paris Hilton, Lady Gaga and the “Real Housewives” star Bethenny Frankel. “But by 2016,” writes Chiusano, “he had found a new role model who brought celebrity glitz and gossip to civics: Donald Trump.”

Perhaps the reason a critical mass of Republicans finally jettisoned Santos is that he was too embarrassing a reflection of the values of the party’s de facto leader. That’s certainly why I, for one, am going to miss him. A gay man and, reportedly, a former drag queen in a party consumed by homophobia and a pseudopopulist accused of bilking his campaign donors to pay for Botox, Hermès shopping trips and the adult entertainment website OnlyFans, Santos distilled the Trump movement’s lurid hypocrisy to great comic effect. In a world overflowing with tragedy, he’s a farce.

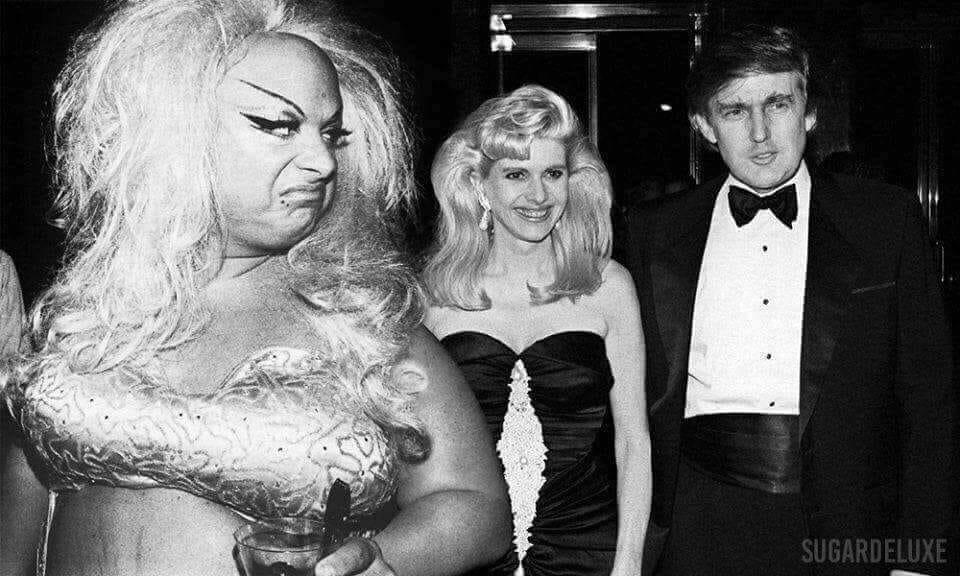

This gestures at something I’ve sensed vaguely and inchoately over the last few years, which is the extent to which Trump himself is a kind of camp figure, and, relatedly, the complex but nevertheless real connections between the aesthetics of camp and those of fascism.

Trump is a figure out of the New York downtown scene, circa 1977-1989, as reflected in everything from Studio 54, to CBGB, to the nihilistic world of American Psycho in fiction, to that of Liar’s Poker in fact.

40 years later, this grotesque figure is now the all but official leader of authoritarian Christian nationalism in America — a nation of which he has been president, and may well be again.

The world is a strange place.