Gaming Notes

Yeah. So. It’s been a rough couple of months, nor are we out of them. As I’ve mentioned in the comments here a couple of times, I’m physically quite safe, but emotionally very despondent, and that latter state has only deepened as the indifference and self-absorption of my government have become increasingly clear. And that, to be honest, is about as much as I want to say on the topic in this post, and perhaps at all. I find the experience of talking about the situation with foreigners—perhaps especially Americans—extremely frustrating, and I’d much rather do the things I’m actually good at and for which I was invited to join this blog.

To which end, it’s perhaps unsurprising that I’ve been looking for distractions recently, and gaming, as I think I’ve said in the past, is sometimes a more effective way of achieving that than reading or watching something. It gives you the illusion of action without the challenges of it. I’ve been lucky enough to discover several games in the last few months that have engrossed and engaged me. I’d like to talk about them—and, to be perfectly clear, nothing else—in this post and its comments.

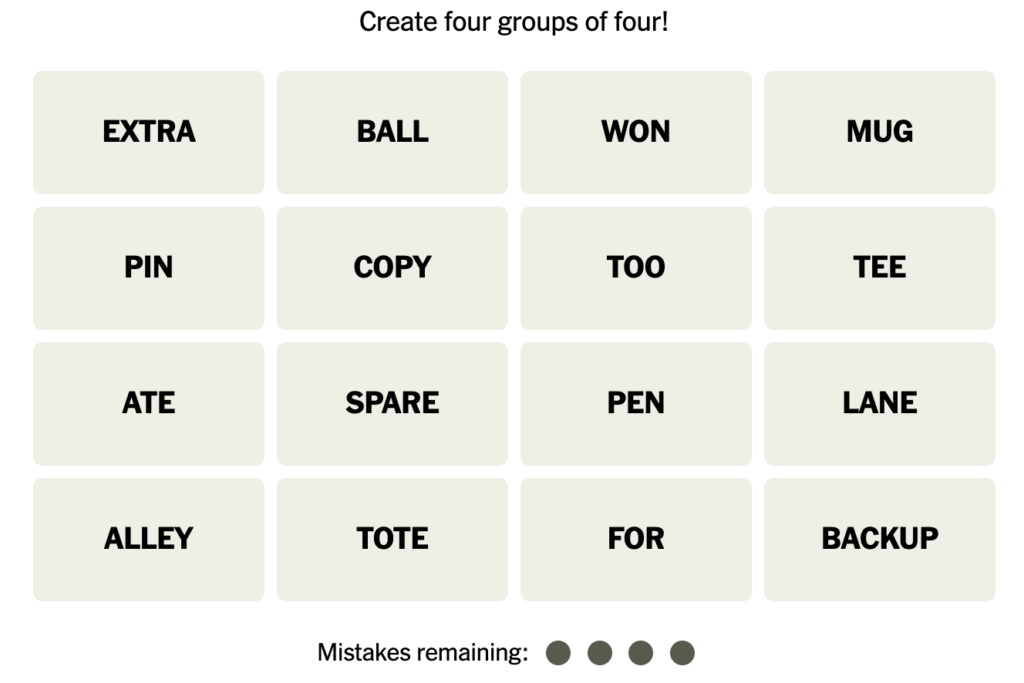

It doesn’t merit a full-length review, but I’d be remiss not to mention a game that has become a beloved daily treat, the New York Times‘s new puzzle Connections. Inspired—as my British friends will constantly point out—by the BBC’s Only Connect, Connections presents you with a board of sixteen words and asks you to divide them into four groups. The common factor can be anything from pop culture references to rhyming schemes to (again, to the chagrin of non-Americans) chain restaurants and sports teams. If you’ve fallen off the Wordle wagon and are looking for a different daily puzzle, it might be worth giving Connections a try.

Finally, because apparently there needs to be a reference to the excellent puzzle game The Case of the Golden Idol in each of these posts, developers Color Gray Games have just announced a sequel game, The Rise of the Golden Idol, to be published next year. As I said in my original review of the first game, the Golden Idol concept is almost infinitely expandable, and I’m delighted to see that Color Gray have found new stories, and new puzzles, to set in this deranged and delightful setting.

And now, the games I’ve played in the last few months.

The Roottrees Are Dead (2023)

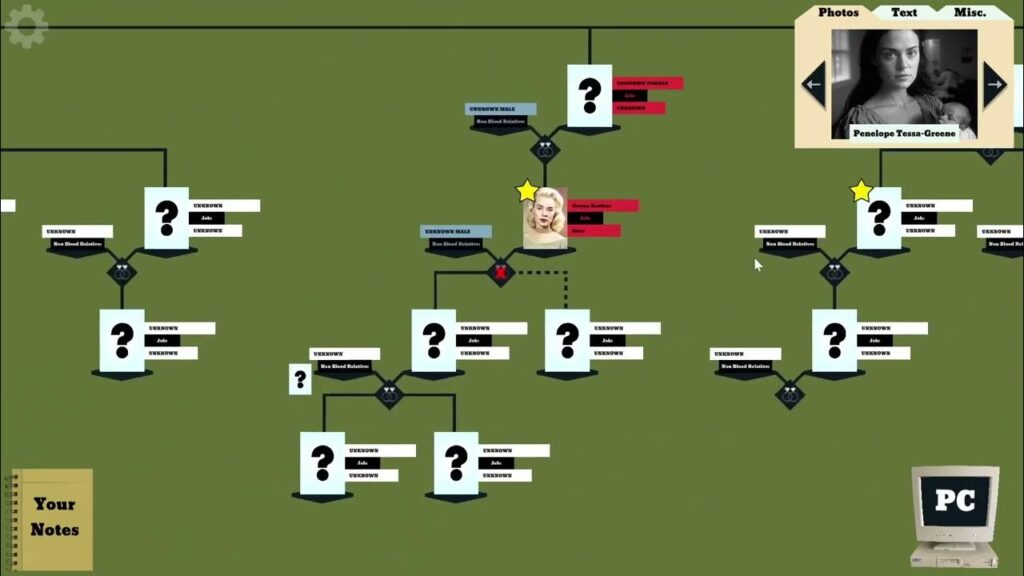

The biggest and most delightful gaming surprise of the year is The Roottrees Are Dead, a free, web-based game by developer Jeremy Johnston whose concept, design, and player experience are all perfectly executed. Inspired by games like Return of the Obra Dinn (2018) and Her Story (2015, see below), The Roottrees Are Dead is a logic puzzle that is also a mystery. CEO Carl Roottree and his three daughters are tragically killed in a 1998 plane crash, leaving the future of the Roottree candy company in limbo. The player is tasked with filling in the Roottree family tree, going back to 19th century entrepreneur Elias Roottree, to determine who is who and eventually uncover a long-held family secret. Using documents and online search engines, the player can pore through periodical archives and book excerpts to place each Roottree on the family tree, along with a picture and their occupation (for bonus bragging rights, you can also place the non-Roottree spouses of family members, and identify additional pictures).

Like the best puzzle games, The Roottrees Are Dead is deceptively simple. The game consists of a large board containing the unfilled family tree, folders for the documents you’ve collected, and the online resources you can access. (In a move that more games should mimic, there is also a notepad where you can collate information rather than reaching for one in the real world.) To begin with, a few of the Roottrees are notable enough to be googleable (or, Alta Vista-able, given the timeframe). But as the game progresses, you have to get more creative—to winkle out references to companies, periodicals, and book titles from the resources you’ve found. As I’ve mentioned in the past, I have a pretty narrow definition of what constitutes a satisfying puzzle, neither too easy nor too hard, and The Roottrees Are Dead falls smack in the middle of it. You need to read documents carefully and think creatively about where information can be found (if the second volume of a scholarly work has proven useful, maybe it’s worth looking at the first volume too?), but the game also subtly points you in the right direction, with “intuition” scores that let you know that a particular resource’s usefulness isn’t completely exhausted, and that you should go back and take another look. There’s also enough redundancy in the available clues that you can complete the game without finding all of them, and without resorting to brute force.

So satisfying is it to track down the various Roottrees that it’s easy not to notice that the story you’re piecing together is actually quite banal. Unlike the lurid tale of murder, theft, and sea monsters revealed by untangling the last days of the Obra Dinn, the Roottree family’s secrets are pretty tame, and even the game’s final revelation packs a relatively mild punch. Given the game’s incredible success, I wouldn’t be surprised if Johnston is currently mooting a commercial version, and if so then this is one aspect that will need to be punched up. But in the meantime, it’s striking how little this ends up mattering. The Roottrees Are Dead is so well-designed, and so much fun to puzzle through, that you don’t really mind how small the secrets it unveils actually are—and after all, isn’t that the case with so many families?

(One additional point worth making: Johnston is releasing the game for free because he used AI-generated art for the documents and photographs seen throughout. For my part, this seems fair—though there is an optional tip jar, which I and I’m sure many other players have contributed to. In fact, if this was the use-case for AI art, to help very small-scale, self-funded creators get their project off the ground, sometimes just as a proof of concept so they can get funding to pay actual artists, I think it would be pretty defensible. But as we all know, that is not why tech companies are pouring millions into the technology.)

Unpacking (2021)

I was in the midst of a real-life move when this game, by Australian studio Witch Beam, became an internet sensation, so naturally it was the last thing I wanted to play. Now that I’ve gained enough distance from the experience, it’s easier to see what everyone was so excited about. Unpacking, as its name suggests, is a game in which you have to unpack and place a nameless character’s belongings—from a childhood bedroom, to a single room in a shared apartment, to her own house. As tedious as that might sound, there’s something very satisfying about how Unpacking realizes its gameplay. There’s surprise when you open each box and discover what it holds. A bit of mystery as you piece together the character’s personality and interests from her belongings. And a lot of creativity in how you choose to arrange these objects in the space available—I found myself, for example, thinking very seriously about the kitchen arrangement in each home. So long as, again, you’re not going through the experience in real life, there’s also a bit of a nostalgic hit to be drawn from the game’s depiction of common moving experiences—the bathroom loofah that has mysteriously made its way into a bedroom box; the janky kitchen implement you’ve had since your first apartment; the t-shirt you’ve been wearing since your teens.

No humans appear in Unpacking, but nevertheless its sequence of rooms, apartments, and houses tells a story. You can tell that the man the main character moves in with after college is a douchebag as soon as you clock the chrome-and-black-marble decor of his apartment, an impression which is confirmed when you see how little space he’s left for her belongings. When you unpack her home office in a later session, it’s extremely gratifying to discover multiple copies of a children’s book featuring characters she’s been drawing for years. But while Unpacking manages to infuse each of its settings, and its main character, with a great deal of personality, there’s no denying that it is ultimately Middle Class Life Trajectory: The Game, going from college to roommates to your own apartment to a house and a nuclear (albeit queer) family. It might have been nice if the game ranged a bit further, and used its premise to explore what the moving experience means to other kinds of people—an itinerant academic moving into an apartment they probably won’t stay in for more than a few years; a divorcé trying to downsize their life and set up a custody-sharing lifestyle; a refugee who is starting from zero. Satisfying as Unpacking is, when it ends you can’t help but feel that there was more to be done with its mechanic than this single, simple story.

Signs of the Sojourner (2020)

Looking back on the last year or more of gaming, one issue that keeps cropping up is the delicate, difficult balance between games that are story-based, and ones whose challenges are procedurally-generated. How do you give players a new challenge each time they play, while also grabbing them with compelling plot and characters? Signs of the Sojourner, by American studio Echodog Games, is a perfect illustration of this problem. You play the child of a recently deceased trader and store-owner, in a post-collapse yet mostly quite cozy civilization. Your late mother helped keep your dying town on the map with her general store, and it’s now your job to do the same, by joining the caravan that traverses the wilderness. To get trade goods, however, you need to develop relationships with the merchants in the towns you visit, and to do that you need to have productive, sympathetic conversations.

Conversation in Signs of the Sojourner is represented by a card game. You lay down a card from your deck with symbols that represent your tone and emphasis, and your partner has to lay down one with matching symbols. Different people use different conversational techniques, so the deck you start with might not be any use with them. At the end of each conversation, you can drop and acquire new cards, which can have new types of characters (representing new techniques), or special traits that make it easier to get through challenging conversations. Successful conversations can not only earn you merchandise for the shop, but open up new travel routes, reveal new information about the world and your family’s history, and allow you to involve yourself in the lives of some of the characters you encounter—to help two ornery brothers reconcile, or play cupid between two aging merchants who live in neighboring towns.

The deck-building mechanic ends up working really well as a metaphor for communication and its challenges. The way it’s used in the game is inherently cooperative—it doesn’t matter how good a deck you build if the person you’re talking to doesn’t have complementary cards. Ultimately, the goal is to build a deck with enough flexibility that you can talk to just about anyone, but the limited number of cards you can accumulate means you sometimes have to make choices, to prioritize certain kinds of people while accepting that you will not be able to communicate with others. And, the further you range and the more conversational styles you learn, the harder it is to talk with the people back home. Certain flourishes in the game correspond strongly to the realities of actual communication—a strong agreement early in a conversation creates a literal shield that can smooth over a later symbol mismatch, or disagreement; as your travels progress, you accumulate “fatigue” cards that don’t match with anything, making conversation more and more difficult; and around the middle of the story, a disaster occurs that introduces a new symbol, grief, into other characters’ decks, which can only match with itself, meaning that you have to show sympathy if you want to connect with anyone.

That last point, however, also points towards Signs of the Sojourner‘s biggest problem, the fact that although there’s a tremendous amount of flexibility in how you can build your deck, and thus how each exchange turns out, the broader progression of the game is fairly fixed. Each character you meet has a set storyline, and certain events always happen in certain configurations. The game world is wide enough—and the limitations of the deck-building mechanic are stringent enough—that you’re unlikely to explore more than a few storylines in each game (much less complete them), but this can also lead to an unsatisfying gameplay experience. You can dedicate your deck to, for example, befriending a junk dealer at a railroad depot, but if you get a bad hand when you try to talk to him for the first time, his entire storyline will be derailed, and you’ll have wasted all your work in this playthrough. It doesn’t help that the opening round of the game is fairly samey—it’s a good half hour before any meaningful choices present themselves—and that the game ends after five trips of the caravan. So there’s no chance to build up a head of steam and explore storylines that you’ve only started to be able to penetrate.

I don’t play a lot of deck-building games, so this might be a skill issue, but after more than a few playthroughs of Signs of the Sojourner I still found myself having trouble exploring very far in the game’s map, and quickly losing the motivation to try. This feels like a design problem that leaves the game teetering on the brink of greatness, an excellent mechanic in search of either much tighter plotting, or more freedom for the player to simply explore.

Her Story (2015)

Playing The Roottrees Are Dead reminded me that I’ve had a copy of Sam Barlow’s groundbreaking FMV murder mystery Her Story sitting on my computer for years. As is often the case when you come to a massively influential work years after it has made a splash, I ended up having a bit of a mixed reaction to the game. It’s obvious why players and reviewers eight years ago found it so shocking and different, but in the intervening years, its techniques have been used by so many other designers (including Barlow himself, who has made two other games with a similar mechanic) that its freshness can feel less significant than some early conceptual issues.

Her Story presents the player with an archive of the 1994 police interviews of a young woman, Hannah Smith (Viva Seifert), whose husband has gone missing and is later found dead. The interviews have been chopped up into one- and two-minute segments, and tagged with each of the words spoken in them (a feat of digitization unmatched, I suspect, in any real police work). The player can search the database for any word, and using that resource, has to piece together Hannah’s statements and the story of what happened to her husband. An important limitation is that the search engine will only display the first five results for each keyword, so once you’ve eliminated the obvious suggestions—the victim’s name, and words like “murder”, “body”, and “cellar”—you need to get creative in order to dredge up more esoteric clips and complete the picture. It’s an interesting mechanic that creates the impression of an investigation—the player has to keep their ear open for significant words, and make mental leaps about what might have been said in other clips according to what they’ve already watched—while keeping the game’s interface extremely simple. In fact, the key genius of Her Story—besides, that is, Seifert’s performance, whose deceptive blankness ends up hinting at some significant truths—is in how it scripts Hannah’s answers so that they each reveal enough of the story to draw the player on and give them the next handhold on their journey, but not so much as to give the entire story away.

Given how painstaking it must have been to script the game in order to achieve this effect, it’s not surprising that Barlow ended up neglecting other aspects of the gameplay experience. In a complete reversal of my reaction to The Roottrees Are Dead, Her Story ends up revealing a sensationalistic (not to say absurd) secret behind the disappearance and murder of Hannah’s husband, but struggles a little to create a sense of accomplishment in the player for unraveling it. Put simply, the game doesn’t have a win condition. A handy chart shows you how many of the 271 interview clips you’ve managed to discover, but nothing happens if you hit 100%—which it is anyway virtually impossible to do without hints; in fact, a small number of clips are undiscoverable in unassisted play, since they break the established rules of the search engine. It’s left to the player to decide when they’ve hit their limit, but even though you will probably have worked out the facts of the case, and some of its more interesting nuances, by viewing 80-90% of the clips, there’s still a feeling of incompleteness. One that is only exacerbated by the strangeness of the events that Her Story eventually reveals, and the very small amount of closure it offers its characters. I still found the experience of playing Her Story engrossing, but the way that it fizzles out rather than ends makes it seem, especially in 2023, more like a proof of concept whose ideas will be taken up by others, than a complete work in its own right.

A Highland Song (2023)

Inkle, the British studio who previously brought us 80 Days (2014), Heaven’s Vault (2019), and Overboard! (2021) are back with a new game, and it’s a… platformer? The player controls Moira, a young girl who lives in seclusion with her mother in the Scottish highlands. Spurred by a letter from her beloved uncle Hamish, a lighthouse keeper, Moira sets out on a journey across the mountains and valleys that lie between her and the sea. The player not only has to get her there in time for Beltane, which is a week away, but to keep her alive—to find traversable routes up and down mountainsides, to identify peaks using fragments of maps and other documents that Moira finds, to locate secret and forgotten pathways that will allow her to make her way from one valley to the next, and to maintain her health by, for example, finding safe places for her to spend the night, or not letting her freeze to death on mountaintops. Along the way, Moira learns about the history and mythology of the region, and pieces together folktales and her own family history to slowly reveal the reason for Hamish’s urgent invitation.

Unlike other platformers I’ve played, A Highland Song doesn’t treat its main character as an endlessly plastic figure with springs in her feet. Moira is injurable—if you let her slide down an incline too fast she will complain about a skinned knee or a wrenched wrist, and her health will decrease. Perhaps more importantly, she seems aware (though arguably not nearly aware enough) of the dangers of her endeavor. The all-too-realistic soundtrack gives you shrieks when she loses her footing, frightened moans when she’s teetering on a high ledge, and panting when she overexerts herself. It’s not actually possible to kill Moira—if you send her over too high a ledge, the game will instantly reset, and if you let her health bar run down to zero, she will go to sleep and wake up elsewhere (albeit at the cost of a day). But nevertheless these feel like weighty actions, with Moira clearly aware that something has happened to her. Combined with the imposing, seemingly impenetrable landscape—in my early runs I often found myself crawling up and down a single mountain for days, looking for a pathway that might not even be there—and the growing realization that the maps Moira has brought with her are simply insufficient for her journey, this makes for a frustrating, anxiety-inducing gameplay experience. As Moira climbs up cliffs, scrambles down mountainsides, squeezes into dark caves, and in general does a lot of things that a person, much less a child, absolutely should not do alone and without a map, one increasingly comes to feel that the only ethical thing to do, as her controller, is march her right back home.

It’s only at the end of the first run, when the game informs you that you will be allowed to retain some of the maps and inventory that Moira had collected, that the trick becomes clear. The goal was never to make it to the lighthouse in time on your first try (I suppose some master platformers could do it, but I was more than a week late), but to amass information with which to make your next try more feasible. The more you play, the more you learn about the region Moira is moving through, and the easier it becomes to traverse it. Inkle has used techniques like this in the past. 80 Days had a wealth of storylines and route options that it would take dozens of playthroughs to reveal; Overboard! expects you to replay its scenario again and again until its main character can get away with murder (and even then, there are multiple possible endings); and Heaven’s Vault not only allows the player to keep their dictionary from one playthrough to the next, allowing them to translate increasingly complex texts and learn more about the game’s setting and history, it incorporates the idea of the loop, of endless repetition, into its story and mythology. It’s an elegant solution to the problem I’ve discussed above, of replayability and fixed storylines. The world Moira has to explore is incredibly wide, and the number of clues you can discover and untangle is immense. I’ve played for around 25 hours on multiple runs, and I still don’t feel that I’ve uncovered even half of what you can come across in these mountains—the history, the secret pathways, the spirits, giants, and beasties you can encounter. Even after you make it to the lighthouse on time, there’s so much left to explore that the allure of yet another run will be almost irresistible. Along the way you start to feel, as Moira does, that these mountains are yours somehow. Learning them, and the ways across them, changes you as a player, and transforms the experience of playing the game from something dismaying into something joyful.

Unsurprisingly for a game that has only been out for a few weeks, there are some teething problems along the way. In some cases these are bugs, while in others, deeper conceptual issues that go to the very heart of the game. How easy do you want to make it for players to identify paths and recognize peaks? How obvious should the shortcuts you’ve already identified be on subsequent playthroughs? How essential is the feeling of being lost, of being dwarfed by the landscape, to the gameplay experience? There have been some instructive conversations on the subject on the Inkle discord server, in which the developers have been impressively present, and whatever conclusion they reach, they reinforce the impression—already strongly made by the game’s painterly graphics and beautiful soundtrack—that the point of A Highland Song is not merely to beat a clock or draw a map, but to become part of a place.